He was, like the rest of the pilgrims, from England. When he was only 12 or 13, he was inspired by the Nonconformist minister Richard Clyfton, who preached a brand of Christianity separate from the Church of England.

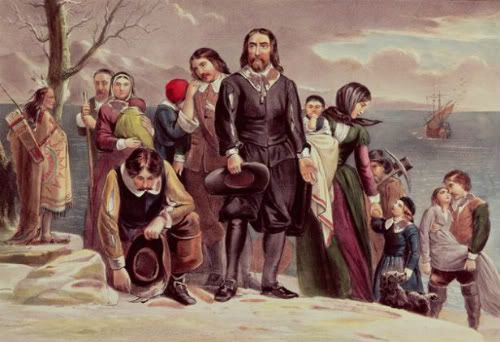

This movement of Nonconformists and Separatists, who opposed a national church, was met with harsh persecution. Going against the Church of England meant treason. Seeking religious liberty to practice their own brand of Calvinist Christianity, these “pilgrims” sought refuge in the New World.

Bradford’s fascinating work Of Plymouth Plantation, describes the trials and triumphs of these early settlers. Of the voyage over and the landing at Plymouth, Bradford writes, “Being thus passed the vast ocean, and a sea of troubles...they now had no friends to welcome them or inns to entertain or refresh their weatherbeaten bodies; no houses or much less towns to repair to, to seek for succor.”

The first winter in the New World was a hard one: “But that which was most sad and lamentable was that in two or three months’ time half of their company died, especially in January or February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy and other diseases which this long voyage and their...condition had brought upon them...there died sometimes two or three a day in the foresaid time, that of 100 odd persons, scarce fifty remained.”

How did they survive? In elementary school, we are presented with stories of pilgrims and Indians living and working happily together, sharing food and friendship. As is often the case with history, the reality was more complex.

The first encounter with the Indians was a battle. Captain Myles Standish and a band of pilgrims encountered a party of Indians and a conflict ensued. Arrows flew, muskets fired, and people died.

But Indian/Pilgrim relations were not all conflict. One Indian who served as a kind of helpful middle-man and peacemaker was Tisquantum, also called Squanto. According to Bradford, “Squanto continued with them [the pilgrims] and was their interpreter and was a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation. He [Squanto] directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities.”

After surviving the harsh winter [with the help of Indians like Squanto], the pilgrims did celebrate a kind of Thanksgiving. However, in Bradford’s account, no Indians were invited or welcomed to this celebration, contrary to popular imagery: “All the summer there was no want...as winter approached, there was great store of wild turkeys...Indian corn.”

With the Indians’ help, the pilgrims learned to survive and thrive. Eventually, many more settlers arrived and “many were much enriched and commodities grew plentiful.” Ironically, as the ranks of European settlers increased, so did want for land. Eventually, as we all know, the Indians who had helped the first hungry settlers survive, were pushed away, killed, and displaced by what would become the United States of America.