AN AMERICAN COMEDY

PROLOGUE

Dear Reader,

This book took me a very long time to write, and a very long time to decide to share it with people.

The genesis of this book was my sophomore year of college. I was attending a private Christian university in Seattle, WA. I grew up in a Christian family in Fullerton, CA. My dad worked for the largest church in town: The First Evangelical Free Church in Fullerton. Up until college, I was a very devout Christian.

Ironically, it was at a Christian university that my faith, and much of my identity, began to unravel. During my sophomore year, I began taking lots of Bible classes. Growing up, I was encouraged to study the Bible, to read it devotionally. But, in college, I began to read the Bible academically. I learned about textual criticism, studied contexts and cultures of when the Bible was written, how it passed through scribes and editors, how a group of clergy decided, hundreds of years after it was written, which books were to be included, and which excluded. To make a long story short, I began to question the Bible as God's infallible word.

To an average college kid, such thoughts might seem normal, even boring and irrelevant. But to me, a sincere, devout, bookish 20-year-old Christian, my doubts and questions were devastating.

My solution to my doubts was to read more, to study more, to grasp at the truth that was crumbing beneath my feet. And the more I read, the deeper my doubts became, and the once solid ground beneath my feet gave way, and I fell into a deep and dark depression. I began having severe stomach pains, intense loneliness, and a level of inner suffering I had never before felt.

In the midst of this, I began to write.

I had always been a pretty shy kid, quiet and introverted. The only outlet for my suffering and confusion were the pages of my journals. Writing became my voice. Quiet and alone, in the throes of pain, I became a writer. I wasn't seeking fame or money. For me writing was, and continues to be, a method of survival. At the time, I wasn't thinking about writing a book. I was just writing.

When my depression became more than I could bear, I returned home to Fullerton, utterly broken inside. But I continued to write. As I went to twice a week therapy, as I tried various anti-depressants, as I started taking art classes at Fullerton College, as I took long, lonely walks through suburban neighborhoods, as I accompanied my parents to church (feeling utterly detached), I wrote. I wrote everything down. One thing that depression can do for you is destroy your ability to lie to yourself. The writing style that worked best for me, that alleviated some my pain, was brutal honesty.

I continued reading, took literature courses, and found, in the voices of writers like Dostoyevsky and Shakespeare and Hemingway and Plath and Achebe and O'Connor and Blake and Byron, kindred spirits, fellow suffering humans trying, in their different ways, to find meaning in this big and lonely world.

Somewhere along the way I began to think about turning my journals into a book. They were personal and weird and tormented, but reading lots of classic literature helped me understand something that had eluded me in 18 years of public education: most of the really good books, the ones that meant something, were about suffering humans trying to find meaning in their lives.

That's what I'd been doing all along. And so, around age 22 or 23, I began compiling my journals into a story, a memoir of sorts.

My biggest problem, for a long time, was that my journal entries were so fragmented and random that they seemed to lack what writers call a "narrative thread." There was no "story arc" that I could see. It was pages and pages of observations, feelings, ideas, drawings. It was, like my head at the time, a mess.

And then I discovered Dante. I had actually read Dante's Inferno in college. Most people are at least aware of that book. It's a 13th century epic Italian poem about a man's descent into hell, the stuff of horror films and goth music…and depressed people.

What many people don't know is that Dante's Inferno is only the first third of a three-part epic called The Divine Comedy. The second part, Purgatorio, is about Dante's slow ascent up an allegorical mountain, as as reaches nearer and hearer to the heavens.

The third and final part of The Divine Comedy is Paradiso, about Dante's journey into heaven, into paradise.

The Divine Comedy is not a comedy in the modern sense. It's not funny. It's filled with suffering and angst and frustration, but it ends well. The classical idea of a comedy is basically a story that begins in misery and ends in happiness.

Something about Dante's epic rang true with me. He wrote it in the midst of a long and lonesome exile. My story, this far, felt like Dante's. I'd been to hell. I was in the process of slowly ascending the mountain of purgatory, of healing. And though I was certainly not happy at the time, the idea of happiness in life gave me hope. I began to believe that happiness was possible, not in some distant afterlife, but here, now, in this life. For a 23-year-old suffering a major depression, this was a revelation.

And so I took the three-part structure of Dante' Divine Comedy and applied it to my book. My experiences in Seattle were hell, a slow descent into torment and loneliness. My experience in therapy, in art classes, in my decision to major in literature, post-hell, were my purgatory. And paradise? When I began compiling my book, paradise was a distant dream, a whisper of hope. Paradise was, to quote the Bible, "a still small voice," a voice that told me, "Don't give up. Keep trying. Keep writing. The story is not finished. This is a comedy, you dummy, not a tragedy, even though it feels like one."

As I continued through college, got my degree, and began teaching college English, I continued writing. Many times, I found myself thinking, What am I doing? I'm not happy. I'm functional, but I'm not happy. For me, purgatory lasted a very long time. About seven years. Interestingly, in those years, as I moved into my own apartment in downtown Fullerton and became an "independent adult," many of my experiences mirrored those in Dante's purgatory. On his journey up the mountain, Dante encounters people with all the classic human flaws and weaknesses, people looking for happiness in all the wrong places…in sex, in drink, in petty jealousies, in power, in wealth. I tried all these avenues (except wealth), and always found myself miserable and empty.

For me, paradise, real happiness, began when some friends and I decided, against all "good judgment" to open a small art gallery in downtown Fullerton. This was in 2008. At the time, the downtown was dominated by bars. Our gallery was a weird little anomaly. But, through the gallery, I found myself starting to share all the passions I'd picked up on my journey of suffering. We had poetry readings, art exhibits, live music performances. And, from the very beginning, our little gallery became a catalyst for artists and writers to come out of their lonely cocoons of torment and see that they were not alone.

The real test, and the real turning point on my journey came about six months after we opened the gallery, when the initial excitement wore off and the financial reality hit. our rent alone was $1500 a month, and there were many months when we didn't sell anything. People came to the shows, but they were mostly like us, poor artists.

It was around this time that a new passion began to stir in me, an idea that changed my life and has made me happier than I ever dreamed I could be. It was not an original idea. It was, in fact, a very old one, an idea the stretched back to my Christian upbringing, to my earliest identity, an idea that would ultimately lead me back to a faith I had long thought impossible.

The idea was this: It is better to give than to receive.

Simple. Cliche. But revolutionary for me.

I began to view the gallery, and other involvements in the downtown community, not as avenues for making myself wealthy, but as gifts, gifts I had been especially well-equipped to give, precisely because of my journey of suffering. The art, music, and literature I'd absorbed like a sponge for years became the substance of my gift.

Now, as part of a vibrantly creative downtown scene, I get to experience paradise every day, in the relationships I've made, in the coffee shops and galleries and poetry and music I hear. The first night of the Downtown Fullerton Art Walk, an idea I'd cooked up a year before, I walked around downtown, past families and students and artists and folks interested in art, and I thought, "For me, this is heaven."

This is not to say that I'm happy and ecstatic all the time. I still suffer depression more often than I'd like. As the wise old Gandalf said, "That wound will never fully heal." But now, in a strange way, I am thankful for my years of lonely exile. C.S. Lewis once said, "The pain then is part of the happiness now."

This is my story, An American Comedy, a journey from hell to heaven, and other places in between. You may be wondering, why does every chapter begin with a letter to someone named Beatrice? Who is Beatrice? In Dante's epic, Beatrice is his muse, a woman who represents love. For me, Beatrice is based on a young woman I met up in Seattle, a woman I actually exchanged letters with for years. The letters to Beatrice are my invocation of the muse, the one who represents the hope of love and happiness in the midst of great suffering.

Sincerely,

Jesse La Tour

Fullerton, CA

December 31, 2011

BOOK 1: HELL

"In the middle of the journey of our life, I came to

myself in a dark wood, for the straight way was lost.

Ah, how hard a thing it is to say what that wood

was, so savage and harsh and strong that the

thought of it renews my fear!

It is so bitter that death is little more so! But to

treat of the good that I found there, I will tell of

the other things I saw."

--Dante, Inferno

CHAPTER 1

“Father, father, where are you going

O do not walk so fast.

Speak father, speak to your little boy

Or else I shall be lost.”

--William Blake

Dear Beatrice,

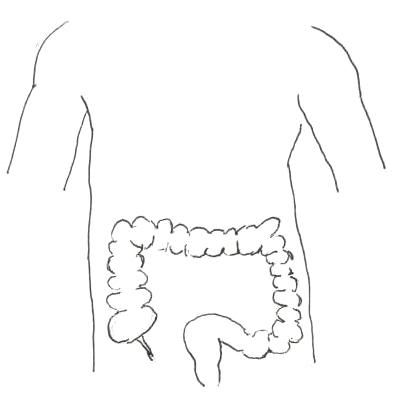

I feel compelled to write tonight, I guess because I’m a little scared of death. For the past four months, my health has been getting steadily worse. First it was asthma, and now a mysterious intestinal thing that makes me wake up most mornings in significant pain. I went to our family doctor over Christmas break, Dr. Ogden, but I don’t think the medicine he gave me is really helping. I hope it is.

I suppose it is the chronic pain that has prompted me to ask the question: Why? What is the cause? Is it psychosomatic? Is it a result of all the psychological/emotional/spiritual problems I’m having? It is stress? A lack of love, of significant relationships, of real human contact? All of the above? All I know is that every day, in the midst of pretty severe abdominal pain, I bow my head and beg God to take this from me, whatever it is, to make me whole again.

I am losing weight. I am losing energy. I can’t remember the last time I actually went out with friends. I mostly just lay around a read and pray that one day I will be able to look back and say, “Man, age 20 was a rough one, but I made it through. Look where I am now. I’m happy. I feel close to God.” I’m actually living each day with that hope in mind.

Sincerely,

Jesse

My dad is a thin man, which is interesting because he comes from Wisconsin, which is full of fat people. But we have lived for many years in Orange County, which is not full of fat people. My dad is driving me back to Seattle for my third semester of college. I go to Seattle Pacific University, a private Methodist University. We are not Methodist. We are Evangelical.

I’m wearing a well-worn gray zip-up sweatshirt, old blue jeans and no shoes. My dad wears cargo shorts, sandals with white socks, and a t-shirt tucked into his shorts. We prefer different styles of clothing.

In our room at the Hi-Lo Motel, My dad and I lay on our beds reading. I’m reading Dostoyevsky’s Notes From Underground. My dad is reading the Bible. And then my dad begins writing in his brown leather-bound journal. I wonder what he is writing. He writes for a living. He is the “communications director” for the First Evangelical Free Church in Fullerton. He’s “ghost written” a couple books for the pastor. I begin writing in my black notebook.

I lay awake in bed in the darkness of this hotel room, pressing a hand against my side to suppress the pain, and thinking about an article I saw in a Newsweek magazine in the waiting room of Dr. Ogden’s office. It was called “Colon Cancer: A Silent Epidemic.” Colon Cancer. The words stick in my mind like a thorn. Colon cancer. Cancer of the colon. I press my fingers around the area where my colon is. Are there lumps?

My dad is snoring peacefully in his bed. I stand up, put on my shoes and sweatshirt, and slip out the door into the cold night air. I lean against a metal railing and look up at the sky full of stars. I close my eyes and grip the metal railing tightly.

Yesterday was a little sunny, but today is bleak. It reminds me of last winter, my first Seattle winter, the rainiest winter in 40 years. It rained for 90 days straight. It was during the winter that I obtained an original Nintendo Entertainment System and played and passed all the games I had never passed as a child: Metroid, all three Super Mario games, Mega Man II, and Contra.

That winter, I played a lot of video games, listened to “emo” music, which was a relatively new genre at the time (this was 1998), viewed porn on the internet, got drunk occasionally, made the transition from a “social smoker” to a full-blown regular smoker, took walks alone downtown, stopped going to church, read The Plague by Albert Camus, and secretly pined for Beatrice.

I remember, near the end of last semester, we were all sitting in the Stearns Cafeteria, and Nathanael blurted out that Beatrice liked me. Beatrice, who I had pined for all year. We lived on the same floor of Hill Hall, she on the girls’ side, and me on the boys’. But, in short, I was too shy and afraid. In retrospect, it sounds so childish, so juvenile, but at that moment, in the Stearns Cafeteria, eating a soggy turkey sandwich, I felt the first chill of despair. She is gone. She moved back to Minnesota, which probably has a lot of fat people too, because it is the midwest and people are less concerned about their weight in the American midwest. Beatrice, however, is not fat. She is just right.

“Goodbye, bud,” my dad says, embracing me.

“Goodbye, Dad,” I say quietly, lamely returning my dad’s embrace.

I watch my dad climb into his white Toyota Camry and drive away.

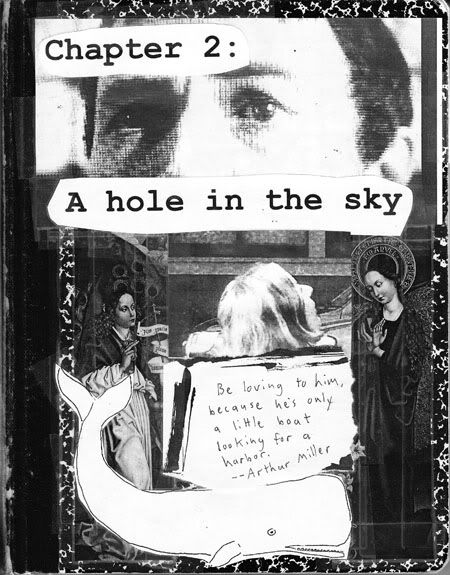

CHAPTER 2

“From then on it was probably necessary to begin to think that there was no center.”

--Jacques Derrida

Dear Beatrice,

I am afraid I am losing my faith in the God of Christianity. I certainly believe in God, because I see no other reasonable explanation for the origin of the universe. Out of nothing, nothing comes. But what reason do I have to believe that Christian doctrine and tradition and the Bible are the true representations of God?

My claim that the God of Christianity is true makes all other expressions of God untrue. The Allah of Islam is false. The gods of the thousands of tribes throughout Africa and Asia and Latin America are false. Not only this, but those people, and the generations of people before them, are destined for eternal suffering in hell. Common sense tells me that this is not fair. What if the only truth is that all cultures develop their conception of the divine?

But, if God is spirit, my experience of Him/Her/It cannot be wholly rational. It must be, in a sense, extra-sensory. But this seems like mere speculation. Have I ever experienced God? Do I really believe in an afterlife? I don’t know. I am terrified to find out. And yet, in the midst of suffering and loneliness, my first instinct is to cry out to God. But it could be reasonably argued that this practice has been built into my psyche since I have been cognitive.

I am utterly frustrated that everything is so uncertain. All I know is what I feel and what I think. And, if these are my guides, I feel I am doomed to perpetual speculation and uncertainty. Some say that God finds us. If so, I say, “Here I am, God. Do you care that I am doubting you? I don’t want to let you go, but my mind is a slave to reason. Save me from myself!”

Sincerely,

Jesse

I walk down 3rd Avenue, down Queen Anne hill. The sidewalk has cracks. Don’t step on a crack or you’ll break your mother’s back. At first I try to avoid the cracks, like a little game with myself. Then I step on a crack and I imagine my mom, way down in Orange County, spasming in intense pain and writhing on the ground. One minute she’s at a garage sale, looking at a pair of Guess jeans, trying to get the owner to accept a quarter instead of fifty cents for them, and the next she’s convulsing on the driveway. I broke her back, by stepping on this crack.

My first class is called “The Latter Prophets.” It’s an upper division Bible class that I’m taking not because I need it, but because I really just want to understand the Bible, apart from memory verses and Sunday school stories.

Last semester I took this class called “Christian Scriptures,” which was basically the whole Bible in one semester. That class sort of like “whetted my appetite” for biblical studies. I read and studied the Bible with new eyes. This book, this painfully familiar book, became unfamiliar, bizarre, awful, beautiful, challenging. Many nights I would sit alone in a corner of the library until closing hours, studying my Cambridge Annotated Study Bible, trying to make sense of these complex, weird stories. The stories they didn’t teach me in Sunday school.

For some reason, my asthma really bothers me in this class--a tightening in my chest and a scary feeling like I can’t draw a full breath. This is how I remember this class--taking detailed notes on the Bible and struggling to breathe.

I walk into my “Latter Prophets” class and take a seat near the middle. A young man with a beard and glasses is sitting in front of me. I recognize him from my “History of Christianity (Early to Medieval)” class last semester. His name is Alex or Allen or something. A_____ turns around and says, “What’s up?”

“Hey.”

“Have you had Dr. Vanderhoven before?”

“I have not.”

“He’s a trip. He’s sort of like the black sheep of the biblical studies department.”

“How’s that?”

“Well, pretty much all of the professors here are ‘canonical critics’ but Dr. Vanderhoven is a ‘textual critic.’”

“Interesting,” I say, pretending that I know what “canonical critic” and “textual critic” mean. (I do not).

Then a chubby, middle-aged man with gray, thinning hair and an almost like unnaturally pale complexion walks in. He’s wearing a t-shirt (one of those “nature“ shirts that has a picture of a wolf in a forest scene, that you get from like a gift shop in Yosemite) that exposes more of his pale body than I would like to see, and shorts that expose more of his stubby, corpulent, pale legs than any man of this man’s age, weight, and complexion should expose to the public, in my opinion.

“Good morning, class,” the man says in a tone that seems, also, oddly inappropriate for the setting. It’s this cheesy, cheerful tone, like the way you might expect elementary (or Sunday) school teachers to talk to their classes.

“My name is Doctor Vanderhoven and this is the Latter Prophets, as opposed to the Former Prophets.” I can’t tell if this is meant as a joke.

“But before I get into the syllabus and all that, I’d like to give you all a little ‘heads up’ (he actually makes quotation signs with his fingers) on my health situation. For the past four years, I’ve been afflicted with a rare disease in which my gallbladder has dried up to something like a bag of sand. Thus, I’ve lived the past four years of my life in a state of chronic severe pain.”

“I’m telling you this,” Dr.Vanderhoven continues, “So that if I am forced to miss any class, you will know the likely reason why. I will either be confined to my bed, or in the hospital.” There is, I suspect, in Dr. Vanderhoven’s cheery voice, more than a hint of weary irony. Dr. V then explains how, although the class is entitled “The Latter Prophets,” the focus will be exclusively on the book of Isaiah, which happens to be Dr. V’s area of specialty. He passes out the syllabus and gives a general introduction to Isaianic studies and textual criticism. I’m paraphrasing and condensing here, because Dr. V is not exactly what I would call “a riveting lecturer,” so I will not try your patience with more of his actual words.

In this first class, I learn that the book of Isaiah probably had at least three authors, who wrote in different centuries, and that most, if not all, of the “Messianic” prophecies that Christians like to point to in Isaiah as proof of the Bible’s divine authority, actually refer to socio-political events from the time of the various authors, and therefore not to Jesus Christ.

I listen to all this with rapt attention, scribbling notes furiously in my spiral notebook.

When Dr. V‘s class ends, I walk toward the door with A______ trailing behind me. He’s trying to kindle some kind of theological discussion. I’m not in the mood.

“Hey, Jesse. What do you think of this? If the Messianic prophecies refer to events from Israel’s history, is it possible that they have like a dual fulfillment in Jesus?”

“That’s an interesting question.”

As I descend the stairs in Tiffany Hall, surrounded by students, I feel something like a small burst in my intestines, followed by a brief, searing pain. I almost fall, but catch myself on the railing.

“You alright?”

“Yeah, I just tripped.”

In the cafeteria I am greeted by the dull roar of hundreds of indistinct voices. I take a tray from a large stack and approach the salad bar. Though I’ve eaten nothing yet today, I have like no appetite. I am eating because I know I need to eat to live. This is survival. I fill my plate with spinach leaves (for iron) and egg (for protein). I find a seat beneath a large window. Suddenly, from behind, I hear a voice, “La Tour!”

Turning around, I see two of my dorm-mates from last year: Clark and Randall, both electrical engineering majors and both missionary kids (MKs) and therefore both pretty socially retarded. Mark refers to them simply as “The Nerds.” Randall is actually carrying some sort of circuit board in one hand and a tray of muffins in the other.

“Hey guys,” I say. Somehow their presence, their total lack of self-consciousness about their uncoolness, has a sort of calming effect upon me.

“Mind if we join you?” Clark asks.

“Not at all.”

As we eat our cafeteria food, we make small talk, catching up on living conditions and how we spent our Christmas breaks (Randall visited his family in Taipei; Clark stayed in his room and played role playing games [RPGs] online). We reminisce on the good old days in Hill Hall (our dorm). I wonder if Randall and Clark are suffering like I am.

My next class is entitled simply “World Literature.” There are only three required texts: Homer’s Odyssey, Dante’s Inferno, and Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

“This is so typical,” I hear a girl next to me say not too quietly to the girl next to her, “We’re only reading texts by white, western men. This is world literature? I thought we were past this sort of hegemony.”

Dr. David Thornton is a thin, balding, bearded man who actually looks like the portrait of Dostoyevsky from the copy of Crime and Punishment that I read over the summer. Dr. T says, “Now, who can give me a definition of an epic?”

For me, a book store is one of the best laxatives around. Whenever I enter a book store, I inevitably have to shit. And so, as I walk down an aisle of the SPU bookstore, scanning the titles of books, I really have to go. This is amplified by the already-present pain in my bowels.

But this bookstore does not have a bathroom. I know this because last semester, when I was buying my books, I (of course) had to shit, but had to walk all the way back to my dorm, and then come back to buy my books.

I can hold it. I will just get my books and get out. Ten minutes. Fifteen max.

My eyes catch the title of a book: Toward a Theology of Beauty. That sounds interesting.

I find the biblical studies aisle and my books: Isaiah 1-39 by R.N. Whybray, Deutero-Isiah by J. Barton, and Trito-Isaiah by A Winterson.

In the literature section, I find copies of The Odyssey (it has waves on the cover), The Inferno (it has flames on the cover), and The Brothers Karamazov (it has a cross on the cover).

Fuck. The line is so long. As I stand in line, holding my stack of books, and testing the tensile strength of my rectum, I hear a familiar voice behind me, “Little La Tour!” I turn and see Simon McNulty and Brad Sanders, two of my brother’s old roommates. It was with these characters that I first got drunk in college, on cans of Miller High Life, at a poker party, and after just four cans I ended up on the floor of a dirty bathroom, vomiting into a paper Thriftway bag.

“Wazzup, little La Tour!” Brad Sanders says, clapping me on the shoulder, so that I almost drop the stack of books I am carrying, and a little shit actually escapes my butt. I can feel it in my underwear. Shit. Does anyone smell it?

“Oh, not much. Just getting my books.”

Brad is tall and thin and blonde-haired and, by conventional standards, quite a good looking guy, though he is kind of a bro. Once, I heard him talking about his girlfriend “tossing his salad” and so that’s the mental picture that usually pops up when I run into Brad Sanders. A girl licking his butt-hole.

“Aiight, take it easy, Little La Tour.” I don’t like that nickname. It literally belittles me.

The pain is still there, and I am trying like hell to contain it. This shit wants out.

CHAPTER 3

"And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust."

--T.S. Eliot

Dear Beatrice,

I’ve been reading about Greek mythology. The Greek gods were so human. Everything hinged on the individual, the frail and helpless individual. I feel like like Daedalus, trying desperately to fashion wings of escape from the maze of my own confusion. But I am fumbling in the dark, pursued by monsters, wondering how I got here, and how I will escape.

Sincerely,

Jesse

I’m trying to put the events of The Odyssey in sequence in my head. The council of the gods. Circe’s island. The Lotos Eaters. The Cyclops. Scylla and Charybdis. Helios and the bulls. Or is that after the Cyclops? My head feels light and cloudy. I struggle to force clarity of thought. This mental exercise-a simple arrangement of events-will prove that my brain still works. But something is wrong. I’m too cloudy.

What is wrong with me? Last semester I remember walking along this same canal, my mind reeling with thoughts so clear and deep and beautiful and complex, they felt more real than the trees and sky and water and geese that surrounded me. I thought wonderful things, intellectual things, as if using my wonderful mind for the first time. Last semester I wrote in my journal, “To fly out of the maze on wings of my own creation!” as I struggled to breathe.

But something is clouding my mind. Like the thing that is laying hold of my gut and making me shit blood and double over with pain. Last semester I thought, Let my body suffer. I have my mind. But the thing in my body has found my mind. And, walking alone across Fremont Bridge, looking through fearful eyes at the dark waters below, I shiver.

I work in Puget Consumers Co-Op (PCC), a posh health food store similar to Trader Joes or Whole Foods, but less corporate. I am a stocker and occasional bag boy. The store has a health foody smell, like spices and patchouli. The smell is half from the products in the store and half from the customers and employees who populate it.

As I enter through the automatic doors and am greeted by Jeff, the pot-smoking juice maker, I feel an emergency in my bowels, a churning and an expanding.

“Hey Jesse,” Sarah, the overweight goth-girl checker says as I wave awkwardly and walk briskly past her toward the bathroom. I feel the handle. The door is locked. Oh shit. It takes all my force of will to keep the shit from escaping my bowels. The pain is significant. I wince and stare at the bathroom door. Someone has put a sticker on it that reads, “The only Bush I want is my own.” I get this image of a puff of curly hair wearing a suit, sitting in the oval office. President Bush. That’s kind of funny, but a searing wave of pain that starts in my abdomen and pulses outward to my extremities rips my mind from all things funny and forced it to focus only on itself.

Finally, when I’m certain I can no longer contain the volcano in my gut and that I will spray blood-red shit into my jeans and down my legs, I hear a flush inside, and the running of water. Hope.

The door opens and Charlie (who works in produce) walks out. Charlie and I exchange awkward wordless glances--the knowing glances of two people who know and recognize the stinking waste their bodies produce, and are embarrassed.

I rush inside, lock the door, fling my pants down, sit down (without using the seat cover--rare for me) and liquid explodes from my colon. When it is finished, I peer down between my legs . The water is a dark red-brown. The sight of it makes me more light-headed.

When finished, I stand up and watch as the red-browm mass swirls down and is replaced by clear water. I stand looking in the bathroom mirror. I look very pale.

Telemachus gets the message. Goes to seek his father. Penelope and the suitors. The island of Calypso. The swineherd. Oh, my swineherd. Wine-dark sea. Wine. Swine. What comes next? Was Calypso before Telemachus? My head, my head.

I am stacking cans of gluten-free soy giblets onto a metal shelf. I hold the can in my hand and a familiar thought enters my mind: What if I just throw it? Just fling it across the aisles and maybe hit some unsuspecting shopper in the head, or at least scare them? It’s a familiar impulse--to do or say the unthinkable. Like in high school when I worked at Longs Drugs and once, opening a box of stationery with a razor box cutter and an old woman with fat, wrinkly legs walked by, and I thought of making just a little slice on the back of her white leg, so thin she would not notice until maybe someone pointed out that there was blood running down her leg.

And now I am stacking cans of organic low fat low sodium black beans. The fight with the suitors, and reclaiming the throne. And that moment when Penolope looks upon her blood-soaked husband and maybe she is horrified and maybe she is glad, or maybe both. What were those lines? I am forcing my mind to recall Odysseus’ first words to his wife, but I cannot. I want to cry. What is wrong with my head?

And then I am filling plastic bins with various grains-spelt, wheat, whole wheat, millet, barley, rye. And, frustrated, I try again to put the events in their proper order: The council of the gods… As if my sanity depends on it. But the pain in my gut returns, and I press my hand to my side and hunch over. I feel another emergency approaching. When I stand up, I see stars. Little flashes of silver are exploding all around PCC. I feel faint, as if I will fall over. As if my head is detaching from my body. As if I am disappearing. I clutch my side and think/pray:

Please don’t let me disappear.

I touch the tops of the grain bins, feel the plastic on my fingers, seek refuge in the world of objects. But my gut still burns and my head still detaches, and my body looks unreal, as if it is another person, as if my head has disappeared. And the emergency is imminent.

In the bathroom, more dark brown-red liquid. Am I dying? Is this cancer. Cast all your cares upon him, comes the voice of my mother. I cast my terror upon him. But those are just words in my head. I cannot literally take my pain or fear and put them on God. I still feel like I am dying, and I bury my face in my hands and, after wiping, when I stand up, the stars are blazing all around inside my eyes.

The face in the mirror is a ghost-face.

I find my manager Tina, a middle-aged lesbian with cancer, and say I feel sick and want to call my brother and go home. Tina says okay.

I am standing outside PCC, under the awning because it’s raining, and it’s also damn cold. It’s really damn cold and all I have is this thin little jacket--just like a half a millimeter of cloth between me and this cold. It’s not enough. I hug myself with my arms, but I can’t keep myself warm.

Finally, Seth arrives.

I run quickly through the rain to his car and get in quickly to avoid the rain. Inside it is warm and music is playing. It’s Counting Crows--Seth’s favorite band. The singer sings, Step out the front door like a ghost into a fog where no one notices the contrast of white on white.

“Hey bro,” Seth says.

“Hey.”

“How are you feeling?”

“Not too good.”

“What is ‘Not too good?’”

“Like digestive problems.”

I think that, after children’s cancer wards and like the slums of Calcutta, and some parts of Africa, emergency rooms are like the most depressing places on earth.

I think it’s funny how that show “ER” represents emergency rooms. I guess I mean maybe there’s some drama in those places, but my experience of ERs has been hours and hours of monotonous, uneventful waiting and waiting, and then hasty treatment. I think there should be a show called “ER Waiting Room.” And it’s just like four hours of people sitting in chairs, watching like “The People’s Court.” Maybe one guy is holding an ice-pack to his head.

So me and Seth are sitting in this ER waiting room and the only thing breaking the monotony is the rising and falling pain in my abdomen. But it’s not exactly entertaining.

Seth is doing a crossword puzzle. He is amazing at crossword puzzles. I suck. My brain doesn’t work that way, or I just don’t have the patience for them.

“Hey bro, what’s the book before Psalms, in the Bible? Three letters.”

“Job.”

“Nice. Thanks.”

A nurse calls my name, and leads me to a room.

I’m standing outside my apartment building and of course it’s raining. I hug my bookbag to myself to protect the books, but nothing protects me.

Then Seth pulls up and I run through the rain to his car.

“Does it ever stop raining here?” I ask.

“Yeah. Give it a few months. How’re you feeling?”

“Okay. A little nervous, I guess.”

“You’re gonna be alright.”

He sings along to the song, I said momma, momma, momma, why am I so alone? I can’t go outside I’m scared I might not make it home.

“C’mon,” he says, “Sing along.”

“I’m really not in the mood.”

“You’re too moody. Sing it out, bro: I belong in the service of the Queen. I belong anywhere but in between. Cus I-y-I am...the Rain King.

“So, how’re your classes?” he asks.

“Okay.”

“You reading anything good?”

“The Inferno.”

“Oh yeah, that’s right. You have Thornton. I had that class.”

“Yeah.”

“Are you reading the Pinsky translation?”

“No, it’s this new one, Martinez.”

“So, what’s your favorite part?”

“I don’t know if I have one. I mean it’s all really good, but I wouldn’t exactly call it an enjoyable read.”

“Yeah, it’s kind of a downer.”

“Literally.”

“Hey, good one.”

Seth parks and we walk inside Virginia Mason Hospital. The electric double doors open and inside is the buzz of activity. Everything is flooded with fluorescent light. It bothers my eyes. A nurse wheels this really fat guy past me in a wheel chair. A man stands by the elevator coughing violently. A very old man is helping a very old woman walk slowly, slowly down a hallway. A baby is crying somewhere. It’s all too much. I can’t sort through the chaos of this world, and my head starts to detach. I am an unreal person amidst real people.

Then I feel my brother’s hand on my shoulder.

“This way, bro,” he says, and leads me to the reception desk.

Inside the elevator is a middle aged woman wearing overalls and a boy of perhaps nine years (She is not wearing the boy; she is with the boy.). The boy’s eyes are red, from either tiredness or crying or both.

We take the elevator to the third floor and find Dr. Samuels’ office. The sign on the door reads:

Gasteronology

Dr. Wayne Samuels, M.D.

Dr. Claudia Jervis-Shin, M.D.

These words flash through my mind: Abandon all hope, ye who enter.

We open the door and enter a fairly ordinary-looking doctor’s office. The paintings are pastel beach scenes. There are plastic plants in decorative pots. It is meant to evoke peace, serenity. But I am aware of its artificial construction. Aware that, beyond this world of beach scenes and fake plastic plants and Better Homes and Gardens magazines lies a world of metallic equipment, machines and devices for probing, penetrating, and cutting flesh. I cannot take comfort in this artificial world.

The girl at the reception desk is very pretty.

“Is this your first time here” she asks.

“Yeah.”

She hands me a clip-board with forms on it.

This bureaucratic necessity makes my head detach more. I am in this waiting room.

“Jesse, you were grinding your teeth again last night,” Mark (my roommate) says.

“Was I?”

“It sounded awful, like you were ripping your jaws apart.”

I nod and walk out of the room.

I step out of the apartment into another overcast day. The rain falls from the opaque gray clouds above. The clouds cover the city like a canopy. I can’t remember the last sunny day. The water pelts my head and drenches my hair, like a baptism I don’t want.

By the time I reach the chapel, I am thoroughly soaked. Students walk by on either side, holding umbrellas and folders and backpacks over their heads to block the rain. My hair is dripping. I think of using the Bible tucked under my arm to block the downpour, but I do not.

Inside, it smells of mildew, incense, and that strange blend of perfumes and colognes that people use to hide their natural stench.

I take a seat in the back, as usual. I look around, at the people still filing in, at the backs of peoples’ heads seated in the pews before me. I look up at the stained-glass window depicting Christ’s crucifixion. I stare at it for a long time, as a man in a Hawaiian shirt gives a talk about missions, as a young man with styled blonde hair leads college students in praise choruses. I stare at Jesus, alone, the suffering Christ, the dying God.

CHAPTER 4

"They fell in, soon enough, with Lotos Eaters,

who showed no will to do us harm, only

offering the sweet Lotos to our friends--

but those who ate this honeyed plant, the Lotos,

never cared to report, nor to return:

they longed to stay forever, browsing on

that native bloom, forgetful of their homeland."

--Homer

Dear Beatrice,

I tried pot for the first time last night. I wanted to feel something different from pain, and I thought pot might be just the thing, but it was not. Last night was the first time I ever really feared for my sanity. The pot changed something in my head, something that did not change back, even after the “high” wore off. I feel somehow detached from nyself. I look at my hands, my body, and it feels like another person. Oh, Beatrice, this is really terrifying. If you still believe in God, please pray for me.

Sincerely,

Jesse

Inside Sam’s house it’s dark and smells like strange incense. The only light is the shifting flicker of the television. Two men sit on the couch--one drinking a beer, the other smoking what I believe to be a marijuana pipe. The coffee table is littered with beer cans and little piles of ash. They’re playing a video game, a fighting game in which the winner gets to actually kill his opponent by tearing out his heart, or his spine, or perhaps by slicing him in half with a sword. Loud rap music blares from two massive speakers on either side of the television. The blending of the rap music with the grunts and wails of the video game creates a chaos of noise. It’s dark in here. I want to leave and I want to stay. The young men do not acknowledge us as we walk past. Their eyes look dead.

“Let me show you my room,” Sam says.

Sam’s room is in the basement of the house. We descend the stairs, and when we enter the dark room, Sam flips on a black light. There’s this huge Bob Marley poster on the wall, and another fluorescent poster with a picture of a colorful mushroom that glows strangely in the black light.

“You wanna see my djembeh?” Sam asks.

“What’s a djembeh?”

He pulls out a large, bongo-like drum from behind a dresser.

“This is a djembeh.”

“Oh, a drum, cool.”

“I take it downtown sometimes when they have drum circles,” he says, rapping the jembeh with the palm of his hand, making a series of booming sounds.

“That’s neat. Can I try?”

Sam hands me the djembe and I rap on it a few times.

“Cool,” I say, and hand it back to Sam.

“So, you wanna smoke some pot?” Sam asks.

“Sure.”

Back upstairs with the loud music and video games, Sam slowly rolls a joint, in deep concentration, as if constructing some delicate and precious thing. I’ve seen this done once, in a Cheech and Chong movie that I watched at my friend Luke Smude’s house in ninth grade.

Then Sam lights the joint and takes a “hit” and then smiles and then hands the joint to me. What am I doing here with these guys? Do I have dead eyes?

“Take a hit,” Sam says.

I put it in my mouth and suck in the smoke, and then take a deep breath, holding it in for a long time. It’s not like cigarette smoke where you can feel the smoke go down. It’s real smooth, and almost undetectable, which makes me wonder if I did it right. But then I breathe out the smoke and I know I have taken a big hit. I hand the joint back to Sam.

We pass around the joint until it’s gone. I take three more hits. On the television, one character is biting the head of another character’s head and there is blood coming out.

At first, I feel nothing, sitting in my chair, staring at the television. Then, slowly, the room around me starts like moving. Is the room moving or am I moving? Does the world move or do I? There is Sam. I cannot hold my eyes on Sam. Everything is moving. That’s nice. Then, it’s not nice. Do I have a fever? What is this room? I don’t want this fever. I don’t want this fever in my brain. It’s not stopping. I am in this chair. I am here. In this house. There is Sam. There’s the TV. There’s that guy. There’s that guy ripping that guy in half. Why is he ripping him in half? I will bring myself back to myself. I cannot.

“How does it feel?” Is that Sam? Who is Sam?

“Alright.” Is that me? Who is me?

No. Not this now. Not this thing in the stomach too. I am doing this thing with the smoke to get away from that.

Now they are passing around a pipe. I take a hit of the pipe. It comes fast this time. It feels good. Thank God. Pleasure. Pleasure is good. But then there is too much pleasure. I am dying of pleasure.

“Hey Jesse, you wanna play me?” That’s Sam. He’s offering me a controller. That’s nice Sam. Sam is nice.

“Okay.” How am I talking? How does that work with the brain and the mouth? And the arms. How do these arms work? That man is stabbing that man with a spear. That man is me. He is bleeding to death.

Why am I smiling and laughing? I just died.

“I can’t.” That’s me. Sam and Joe and that guy are laughing. The room is laughing.

There are chemicals in my brain. Just these little chemicals. Pretty chemicals. Happy chemicals. Sad chemicals. Pain chemicals. That’s all it is. Just chemicals.

In Nathanael’s car, loud music is playing. Love...Love will tear us apart...again. We park on the street in a suburb. The night air is cold, but it’s not raining. We approach an old house. Young people stand on the porch, talking, and smoking, and the upstairs window glows with a strange blue light.

I follow silently, waving at a girl I recognize from my Romantic literature class last semester. She has a cute face and a fat body. She is sitting on a couch on the porch, holding a bottle of beer in one hand, and a cigarette in the other, and talking loudly to a young man who sits beside her.

I follow Nathanael and Mark into the house and we enter into another, darker, warmer world, more alive with sound and movement.

Many dancing bodies. A very crowded room. Show me show me show me how you do that trick. The one that makes me scream she said. The one that makes me laugh she said. O Beatrice. Nathan dances and weaves through the crowd. Matt and I follow in his wake, not dancing. It smells of beer and perfume and bodies.

The kitchen is light and crowded. A few girls lean against the counter by the sink, talking and mixing cocktails, and others sit around a table, eating chips and salsa and drinking shot glasses of tequila.

Nathanael walks toward the girls by the sink and begins talking to them as if he knows them very well (he does not). He is mixing drinks. Then he hands one to Mark and one to me.

“Tequila Sunrise,” he says.

We stand awhile drinking our sweet cocktails, listening to Nathanael talk to the girls.

Back in the living room. Punctured bicycle on a hillside desolate. Will nature make a man of me yet? Nathanael and Mark dancing with the girls, me sitting in a chair by myself, against the wall. Nathan keeps giving me these “Get your shy ass out here and dance” glances. I’m sitting and sipping my Tequila Sunrise.

Oh, my fast beating heart. The dancers, the pulsing music, the darkness, the smells. The bodies and the music move together.

I find a bathroom. My shit is blood.

I can’t bear this fear. I stare into the toilet bowl at the red water, and I see a faint reflection of my face in the water--the ghost-face. I flush the toilet and watch the red wash away and return to white again.

My face in the mirror. I look older and thinner and more tired than I’ve ever looked. I’m an old man, sickly and frail, staring at himself. I will die soon. Who is that man? The muffled sound of the music from the living room. Loud knocking on the door.

“Just a moment,” I say weakly. I splash some water on my face, run my fingers through my hair, and open the door. It’s a girl, waiting. The putrid, lingering smell of my shit in the bathroom and I am embarrassed. I catch the girl’s eyes for a moment, blush, and then look down, and walk past her back into the living room and the loud music and the darkness and the dancing people.

Mark and Nathanael are still dancing with the same girls. They are attractive and youthful and full of life, thinking only of dancing and music and kissing and the tingling desire for the touch of another young body. Why ponder life’s complexity when the leather runs smooth on the passenger seat?

I am a thing cut off, an objective observer. Do they understand the importance of these moments? Are these moments important?

Mark and I are sitting at the kitchen table and we are eating tofu stir fry that I made. It’s my first time making tofu stir fry and it’s not very good. Mark is writing in a notebook.

“What’re you doing?” I ask.

“Working on my philosophy paper.”

“Oh yeah? What’s it on?”

“My working title is ‘God is not omnipotent.’”

“Interesting.”

“Yeah, I’m basically arguing that the Christian notion of an omnipotent God is rationally untenable. I’m using Cartesian logic and a bit of Kant.” These names mean very little to me.

“So, why isn’t God omnipotent?” I ask.

“I guess my argument is a more complex version of the ‘Can God create a rock so big He cannot lift it?’ paradox. Or, can ‘God create a square circle?’”

“It does seem impossible.”

“Exactly. There are things even God cannot do.”

“Do you believe in God?” I ask.

“Of course not,” he replies, as if the question is ridiculous.

“So what does it matter whether God is omnipotent or not if you don’t even believe He exists?”

Mark brushes his long black bangs from his face with the back of his hand and says, “It’s not about God. It’s about making a fucking argument.”

I sit there processing this statement, and chewing a piece of bland tofu. Then I try to imagine a square circle. And then I imagine God as a man, like a body builder, struggling, struggling to lift an enormous rock. And I think of Atlas holding the world, and it toppling off his shoulders. And I think of Sisyphus pushing that big old rock in Hades, and hard as he tries, he cannot push it all the way up the hill. And I think of the song, “He’s got the whole world in his hands.” And I imagine these enormous hands, the hands of God (They look like the hands of my father), struggling to bear the weight of a very heavy world, and then dropping it and it falling, falling, into the infinite black abyss of space.

CHAPTER 5

“He was in full possession of his physical senses. They were, indeed, preternaturally keen and alert. Something in the awful disturbance of his organic system had so exalted and refined them that they made record of things never before perceived.”

--Ambrose Bierce

Dear Beatrice,

People tell me that sin is cultural, that we have created the concept of “sinner” and “original sin” through a long tradition of Judeo-Christianity. Once, when I was 14, I pointed the barrel of a pellet gun at a small finch and blasted off half its face. But then I cried.

I have done things that have made me feel guilty. But, if I’m honest, that’s not all of who I am. I have walked alone along a boat canal in the evening. I have cried at the words of Ernest Hemingway. I have cried myself to sleep at night for no other reason than a general feeling of sadness. I have felt genuine compassion for an old man for reasons I couldn’t understand. I have been aftraid to fall asleep at night for fear I would not wake in the morning. I have played frisbee with my brother on a crisp morning when the grass was white with frost.

I will say that I am incomplete, that I have never known “completeness.” I want to find it in God. I want to raise my hands and finally and really understand this grace I’ve heard and talked about all my life, but sometimes it just seems so unclear, and of a different sort than I understand. I expect it to be unexpected, and I desperately want it to be real. But I am afraid that this “real” might be quite different from what I suppose it should be.

Sincerely,

Jesse

I’ve heard about students who visit their professors during office hours and have terrifically interesting conversations. My brother is one of these students. I’ve seen him walking across campus with professors, engaged in what I presume to be terrifically interesting conversations. I am not one of those students. In my college career thus far, I’ve felt pretty intimidated about talking to a professor in a one-on-one setting. I have trouble holding conversations with my friends. How could I hold a conversation with the possessor of a doctorate degree? What would I say? I would sound like a dumb-shit.

But today I am visiting a professor during office hours and I don’t completely understand why. I don’t have a class-related question. I don’t have a gripe about my grade. And yet I am ascending the stairs of Tiffany Hall toward the office of Dr. Luke Reinsma. I guess I just want someone to talk to. A confessor of sorts.

“Jesse! Come on in!”

“Hello, Dr. Reinsma.”

“Have a seat.”

“Thanks. Are you busy?”

“Nope. What’s on your mind?”

He has this like nervous habit of messing up the hair on the front of his head as he’s talking, so it looks like a big gray poof.

“I just sort of wanted to chat.”

“Splendid. Let us chat. How’s life?”

“Okay, I guess.”

And then I say, “There’s this thing, like a question, that’s been bothering me.”

“What’s that?”

I look at my shoes as I say, “Well, I think I’m in the midst of, like, a crisis of faith.”

“Meaning what?” He messes up his hair for the third time.

“Meaning I’m having pretty serious doubts about Christianity.”

“Okay, like what?”

I think a moment, playing with a piece of rubber from the sole of my shoe, and then I say, “Like I’m not so sure about the idea of hell. I mean, what do you think about hell?”

And then he messes up his hair and says, with a kind of strange conviction, “I stopped believing in hell ten years ago, when I visited China.”

“Really?” My abdomen cramps badly.

“I was working with these wonderful Buddhists, and getting to know them pretty well, and I just refused to believe that these people, and all the billions of people in places like China who believe things different from me, are going to hell. It seemed morally absurd.”

I sit for a moment, nodding, and registering the fact that a professor at a Christian university has just confessed to me that he doesn’t believe in hell. I was kind of expecting some sort of comfort. I wanted an educated man, an older man, to affirm that he was still a believer. But Dr. Reynolds was instead reinforcing my doubt. I was not comforted. I felt more alone.

I’ve got this idea for a story. I think there’s something important in my head. I’ve been thinking about death lately, like the thing in my gut is colon cancer and I might die young. I feel I have to write. I imagine writing a great story--a story that will live after I die. So, I take out my black notebook and pen and write.

The temperature is brisk, borderline cold. The chill air stings my face and hands. There’s the soccer field. A layer of white dew on the artificial turf looks like frost. Seth and I played frisbee there. How long ago was that?

There’s the university, good ol’ SPU. What’s Professor Vanderhoven doing today? Maybe bedridden, with his gallbladder problem. It’s cold and the sky is cloudy. I look for patterns and recognizable shapes in the clouds. There are no patterns or recognizable shapes.

The boat canal is lined with dying sycamore trees and a bike path runs along it. This man and woman zoom by me on fancy Trek mountain bikes. They are wearing skin-tight biking gear, like scuba divers, with these hoods that conform snugly to their heads. A long, skinny crew boat glides past me on the canal. I like how they all row in unison, but I don’t like how there is a man who is not rowing just sitting on the front of the boat and barking instructions at the crew. And how there is another man in a small motor boat riding beside the crew boat, shouting at the crew with a bull horn.

Canadian geese peck the grass beside the bike path. They’re pretty big and scary, like if they all decided to attack, they could eat me alive, so I keep my distance.

If you squint your eyes and look at these trees, they look like giant people, like ghosts, reaching their arms to the sky. My breath exhales white mist into the cold air.

The ground beneath my feet. Rocks and grass and sticks and dirt. Each individual rock, each blade of grass, each stick, each piece of dirt, every molecule is separate. I can’t fit them together. There are too many things in this world. Millions of things. I close my eyes because it is intense to look things.

“Watch it, Mack!” I walk into a jogger.

“Sorry.”

I feel my abdomen, which hurts. Are those lumps? Maybe it’s just the muscle or organs. Colon cancer. I’m going to die. I will die before the semester ends and people will go to my funeral. What will they say about me? My brother will find that story I wrote and send it to a literary journal, and it will be published. I’ve got to leave something behind.

Geese honk noisily overhead. They are perched on the branches of the sycamores, and sometimes they defecate into the water, making little splashes.

Standing on Fremont bridge, watching a giant barge pass underneath that is filled with fragments of broken cement. How do those pieces fit together? And what do they make?

The neon sign says Public Market.

It’s crowded. Too many separate faces. A child atop the bronze pig statue, and his father taking a photograph. Behind the pig and the child and his father, the fish market. A crowd of tourists. The men in bright orange rubber overalls, talking loudly throwing fish to each other. The crowd smiles and laughs and claps their hands as if they are at a magic show and not a fish market.

I walk past the crowd, past the fruit stands and flower shops and food vendors, past a man who is selling many varieties of flavored honey. Open jars on the table in front of him. He is saying, “Free samples, taste nature’s goodness, fresh honey!” The old Asian women at the flower stand cutting the stems of flowers and making bouquets to sell for five dollars, talking quickly among themselves in speech I do not understand. Not beautiful. Painful. Each face, each flower, each piece of fruit, each color, each item separately. I cannot form them together into a complete picture, into a coherent whole. I see in fragments. I feel compelled to close my eyes.

I’m hungry. Three dollars in my pocket. I’m usually pretty short on cash. An old hot dog stand. An old man wearing a paper hat. A hot dog and a Pepsi.

The boats and the houses and the buildings on Puget Sound. The light scatters and plays upon the surface of the rippled water.

A young couple leaning against the metal railing, embracing each other, talking close and occasionally kissing.

An old man, a bum, vomiting into a trash can. Quietly. White vomit dribbling into the open trash can. He is very dirty, and his hair and beard are disheveled and gray, and now with dribbles of vomit in his beard. My abdomen hurts.

3rd avenue. McDonalds. Another homeless man sitting on a bench. The man’s eyes meet mine and he extends his hand.

“Could you spare some change?”

The man’s sad, intense eyes. What oceans of woe surge and swell behind those eyes? The thousand yard stare. You get it when you’ve been in the shit too long. I am in the shit. Two quarters in the dirty, outstretched hand.

“Thank you, God bless.”

Pine avenue. The individual cars. Toyota Camry, a Chevrolet minivan, a Buick Le Sabre. The advertisements on the buses creaking and stopping. McDonalds: I‘m Lovin’ It. Enter the Matrix. Just Do It. The squeaking brakes. My head, floating above my body. My side. This is my body. This is the world. The buildings. Citibank. Travelers. Merril Lynch. The faces, the people streaming past, all around, the endless distinct faces. The lines on the sidewalk, the pieces of garbage, the shop windows with bright signs (Mitso Sushi, Panda Express, Watches Repaired, Closet World, Live Nude Girls. Nude Nudes.). What are nude nudes? People with no skin? Their organs and blood exposed. Even the air hurts. The poisoned air. A crow in the sky. I wish I had a video camera, then I could at least capture it all, and then later go back and try to make sense of it. It’s all too much. I have to close my eyes. Something has happened to my eyes. My eyes and the world.

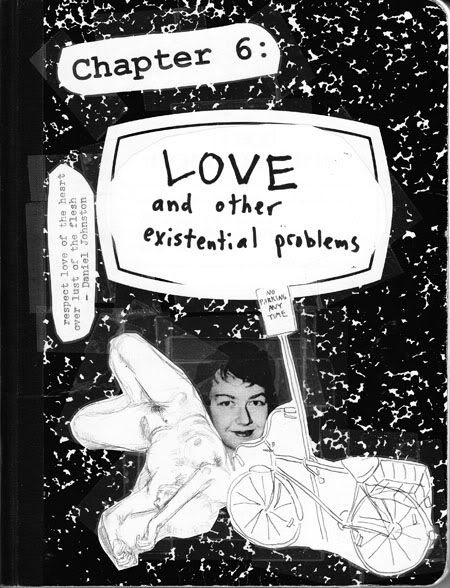

CHAPTER 6

"You show us hard things. You make us drink the wine of astonishment."

--Psalm 60

Dear Beatrice,

When my brother found me, I was shaking. My thin hands balled into pale fists. My eyes pressed firmly shut. A look of anguish. Lines formed here and there on a face once smooth. The sound of grinding teeth.

I was not the brother he knew. I was frail and weak and doubled over and unable to stop from shaking.

I felt his hand on my hand.

“Brother, are you okay?” he asked.

“No, Seth,” I said, “I am not okay.”

When I opened my eyes, I could see that he was crying.

Sincerely,

Jesse

I’m laying awake in bed and it’s late morning on a Sunday. I’m not sure what time. My mom just called and left a message that went something like this:

“Hey bud. Just calling to see how you’re doing. You’re probably at church. But give a call back whenever you can. (And then to my dad: “Say hi to Jesse.”) My dad: “Hi bud.” My mom: “We love you.”

And then I sort of come apart. As a kid, I was a real crier, a real sensitive type. But some time around junior high or high school, for whatever reason, I just stopped crying. I can’t really remember the last time I cried. But now I start crying, and I’m afraid Mark will hear me on the bottom bunk. I smother my face in my pillow and just let loose. Through my tears, I start whispering into the pillow, “Oh God, Oh God, Oh God.” It is more than I can bear.

I lay awake in great pain and my abdomen is cramping very badly. I take two of the anti-inflammatory pills the doctor prescribed, but they do not help. I slide down from my bed and stand a moment staring at my dresser, and the wall above it, where I taped pictures of my family.

I go into the bathroom, fill the toilet with more blood, look at it with benumbed horror, and wash my hands. I take a shower, get dressed, grab my backpack, and walk outside into the cold rain.

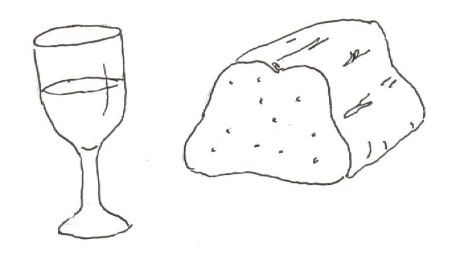

I enter the chapel and sit near the back in my usual place. After scanning the familiar sights--the stained-glass window, the cross, the backs of peoples’ heads’--my eyes fix on the wooden engraving of the Last Supper behind the pulpit.

I am started from my thoughts by the sound of a voice coming from the front of the room. A familiar man in a polo shirt holds a Bible and reads. The words are so familiar that I do not even listen, I only catch fragments:

... He reclined at a table ... eat this Passover ... I suffer ... I shall never again eat ... the kingdom of God ... a cup ... fruit of the ... some bread ... He broke it ... This is my body ... in remembrance of Me ... My blood.

I stare at the stained glass window depicting the crucifixion.

When the man in the polo shirt finishes reading, he invites the congregation to take communion. Two young men stand at on either side of the stage, holding loaves of French bread and bowls of grape juice for dipping. A praise band takes the stage and begins playing various contemporary praise songs.

I slowly walk toward the front of the chapel, with my head lowered. I want to double over and lay on the ground. I clench my fists and bear the pain and whisper to myself, “Let this cup pass from me.”

Finally, I reach the young man and tear off a piece of bread and dip it in the juice and put it into my mouth, almost mechanically. And yet, as I chew it, the pain in my side is so great that it takes great effort to keep from crying out.

I lay awake in bed. I am curled up in a ball, clutching my pillow to my abdomen in a vain attempt to suppress the pain. I’ve just taken three times my normal dose of anti-cramping medicine, and it does nothing.

In times of trouble, my mom often quotes the verse, “Let your requests be made known to God.” I pray, “My request is that You would take this pain from me. And don‘t let me die.” But God either does not hear, does not care, does not exist, or simply chooses not to answer my request. I am deeply disturbed by all of these possibilities.

I am lying on an operating table on my side. Dr. Samuels is ramming a three foot lubricated flexible scope deep into my colon. I am awake.

The nurse gave me Demerol and said I wouldn’t feel anything and would probably be asleep. But I am awake and I feel everything. Every twist of the scope. Every poke against the walls of my insides. And sometimes it is excruciating.

A monitor behind Dr. Samuels shows the inside of my colon as the scope probes deeper. I see little traces of shit. I see blood. This is my body.

“And we’re comin’ round another corner,” Dr. Samuels says in a sing-song way , almost to the tune of “She’ll be comin’ round the mountain.” It hurts real bad, like someone is stabbing me.

Do I have cancer? I crane my neck to see the screen. Is there black? What is that? Blood? It looks like hamburger.

“Just relax there, Jesse,” Dr. Samuels says in his nonchalant way, and a nurse places a hand on my head, gently forcing it away from the monitor.

But I have to look. I struggle against the hands that won’t let me look.

I cannot form the thoughts in my head into sounds from my mouth. It feels like that dream where you are being chased by monsters and you try to run but you are in slow motion. Do you know that awful dream?

I have to force my thoughts into my mouth, but it is so very difficult, like speaking underwater. Finally, in fragments, I hear myself say:

“Do I…have…cancer?”

And Dr. Samuels does not appear to hear. Why can’t they hear me? All around are lights and machines and masked faces and instruments and the monitor. The monitor contains my fate and I cannot see it. My eyes roll around inside my head.

I am falling.

And then the dream with Kermit the Frog.

Kermit the Frog is standing outside an industrial building and he is in his reporter’s uniform and he says, “Kermit the Frog, here!” and he gives his report but the words don’t make sense and I only know that something bad is inside the building.

And sometimes I think that Kermit the frog is my father and sometimes I think he is me.

And now I am inside the industrial building and Kermit is still reporting, cheery and charming as ever, but his words don’t make sense.

Inside the industrial building is a big vat of fiery chemicals with a monster inside who looks like a Sesame Street character, all dopey and shaggy and puppet-like, but he is covered in fiery chemicals too, so he is terrifying.

I am being lowered into the vat of fiery chemicals. And I can still hear Kermit the Frog reporting--just sounds that are not words, or maybe I cannot remember the words.

I am being lowered lower and lower and I think I might die of fear. I do not want to die from chemical burns.

This is where the boy wakes up. Just above the vat. Just out of reach of the fiery monster. The boy forces his eyes open and lies awake in his room shaped like the letter “L” and takes comfort in the sports figures who populate his wall: Magic Johnson, Bo Jackson, Nolan Ryan. The boy may not fall asleep again, but he is safe from the monster. He thinks the monster lives in a real place--in another world he enters when he falls asleep. He does not think the monster is inside his head. The boy wakes up and forces his eyes open.

But the young man does not force his eyes open. He descends into the vat of fire and chemical and monster. And it hurts like hell. It is bitter as death. But he does not die, though his body is enfolded in flames. The young man knows that the monster is inside his head and so he faces the monster. And he does not die.

CHAPTER 7

“He looked up to the sky, doubting whether there really was a heaven above him. Yet there was the blue arch, and the stars brightening in it.”

--Nathaniel Hawthorne

Dear Beatrice,

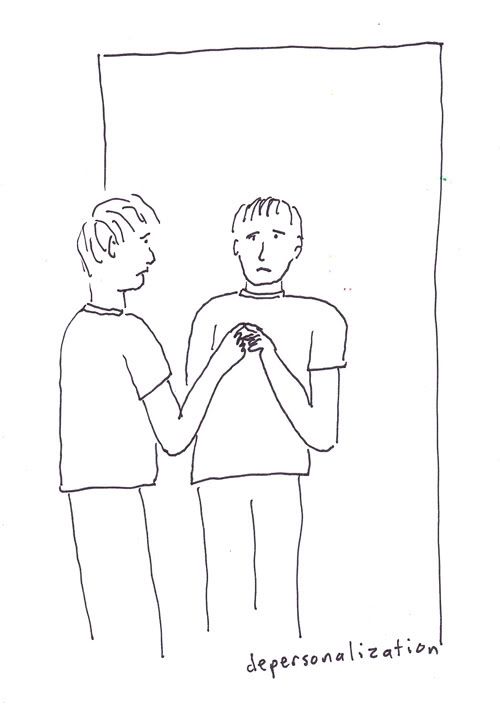

It’s really quite amazing what the body will endure. I’ve learned that about myself. I can bear a lot of pain for a long time. My mind sort of detaches itself from my body and, though I can still feel the pain, I can like mentally distance myself from it, so it’s like another person’s body. In psychological terms this is called dissociation or depersonalization. It’s what rape victims and victims of abuse and war and torture often do. It’s ironic that, once the physical pain stops, this dissociation becomes a new kind of torture.

Sincerely,

Jesse

When I wake up, I notice two things. First, my mom is sitting beside my bed. Second, I am not dead.

And then I notice everything, like all at once: the fluorescent lights that bother my eyes, the lime green paint on the walls, the beeping, tubey, metallic medical equipment, the woman laying across from me in another bed, her head lolling to one side and her mouth opening and closing wide, but no words emerging. God, do I look like that?

My mom is saying something, but the words are far away. I strain to hear, but catch only fragments: “Bless ... healing hand ... mercy.” Oh, okay, she is praying. I close my eyes, out of respect, until I hear “Amen.”

When I open them again, Doctor Samuels is standing at the foot of the bed. I am embarrassed because he might have seen my mom praying. I want to apologize, but my mouth will not form sentences, only sounds that no one understands.

Dr. Samuels is talking to my mom, but his words don’t make sense. Again, I catch only fragments: “Ulcerative colitis ... scar tissue ... inflammation ... comfortable .. wakes up.”

A needle is stuck in my wrist. I hate needles.

I am surrounded by people I know-family, friends, acquaintances. I am here. Alive. It's my brother's engagement party. Seth is standing a ways away, beside a small park bench overlooking Puget Sound. He is on one knee in front of Christine. She is holding her hands in front of her mouth. All these people are watching this private moment, and my dad is taking pictures.

And now all these family and friends and acquaintances are making a tunnel by connecting hands. My hands are touching my Aunt Mary’s hands, and through the tunnel I can see Seth and Christine running across the street, holding hands, and I think Christine is crying. And now they are running through the tunnel of people and Seth is smiling and Christine is smiling and crying and sometimes making little wails.

My brother is engaged to be married. I will never be married.

I wonder if anyone notices the distance in my eyes, if I look thinner than before.

“Jesse, hey big guy!” my grandpa Glenn says enthusiastically in the way he said to me when I was a child. Grandpa’s t-shirt reads: America: Love it or Leave it.

“Hey grandpa,” I say, trying and failing to match his enthusiasm. My attempt comes off forced and fake-sounding to me. It’s still so hard to appear to be feeling okay. I still want to close my eyes and go to sleep and disappear. I am exhausted.

The pain has moved from my abdomen to my head.

And now Seth and Christine are standing in front of me. And this feeling of detachment is so intense that I feel I am clawing my way through metal wires just to converse, just to stay in reality.

“Hey guys, “ I hear myself say.

“Hey Jesse,” Christine says.

“Hey bro,” Seth says.

“Congratulations,” I say.

And now we make a three-person group hug and, for a moment I close my eyes, only feeling their hands on my back and I am reminded that this is me, I am here, and for a moment the pain subsides.

But then my parents walk up and I find it hard to look them in the eyes. I force myself to look at my dad and the detachment intensifies so much that I don’t think I can bear it any more.

The detachment is stronger around family than around anyone else. Why? And then a crazy though tells me that it is love. I cannot bear love, so I detach. I don’t know how to feel it in my heart, so I feel it in my head, but my head doesn’t want it either. I look at my brother and soon-to-be sister-in-law. They are in love. How can they bear it?

I am with my father on an airplane--Alaska Airlines flight 132 to Orange County (John Wayne) airport. It’s a Boeing 737. As a boy, I wanted to be a pilot or a doctor or an Olympic track and field star.

My dad is writing in his brown, leather-bound journal. I watch his hands as he writes. I can see two large veins puffing out. I remember, as a boy, pushing on these adult veins with my little boy’s finger. They were soft. My dad’s hands are wrinkled--too wrinkled for his age. But, then again, so are mine. We have old man’s hands. His wedding ring is a silver band with a cross engraved on it. My fingers are ringless.

I wonder what he’s writing. My father is a writer, like me. I remember, when he edited the town newspaper in Mt. Horeb, Wisconsin, he used to write stories. Stories based on his childhood in Moose Lake, Wisconsin. In his stories, there was this kid named Fran, whom he used to bully endlessly. Like once he gave Fran these really hot peppers form his mom’s pepper plant and Fran practically puked. Another time he almost electrocuted Fran with a mini generator. Poor Fran. I always got a kick out of those stories. He wrote this one called “Warts and All” about how his hands were covered with warts when he was in the fourth grade and this girl still held his hand for square dancing. I liked that story.

I’m reading a story by Flannery O’Connor called “Everything That Rises Must Converge.” I like Flannery O’Connor.

And now the plane is taxiing onto the runway for takeoff. For some reason, I look at the side of my dad’s head, at his neatly-cropped, conservative hairdo, at his mildly receding hairline (which makes his forehead look bigger than it used to), at his glasses (the right lens is much thicker than the left--he has a “lazy eye”), at his freckle-less skin. I guess he senses me staring at him because he turns and looks back at me. There is this strange moment when we’re looking each other directly in the eyes and nothing is said. I see, or sense, the sadness in his eyes. And I feel that he sees the suffering and distance in mine. Nothing is said between us.

And now we are taking off. This is my favorite part. Many things scare me, but a plane takeoff is not one. It feels like a ride--the muffled scream of the engines, and the force pushing you back in your seat, and then the feeling of being airborne, and watching the slowly widening distance between yourself and the ground, and the ever-expanding perspective of the landscape. You are flying.

We are soaring towards the gray cloud canopy that covers the city like a shroud, and suddenly we are in the midst of the clouds. Looking out the window, all I can see is a gray fog. But we ascend higher and suddenly we are above the clouds and the sky is everywhere blue and the sun is shining so brightly that I have to shield my eyes from its glory.

END OF BOOK I

Dear Beatrice,

If I stacked these journals, notebooks, and sketches into a pile, they would form a mountain of fragmented words, ideas, images, and memories, the weight of which could make me fold my hands in despair and give up this whole fragile enterprise. But today, December 15, I sit alone in Starbucks across from a pretty girl who reminds me of you, and I begin to re-read one journal. Just one. The first of my California journals. I can handle one. And this is how I will proceed. One by one. Word by word, sentence by sentence, I will ascend the mountain that stands before me.

Sincerely,

Jesse

There’s a buzzing in my head. I can’t hear it, but it’s buzzing, like the buzzing of bad electricity. Everything is intense. I look down at my body, my torso, my moving legs, my hands and then at the sad face of my mother. Oh mother. Where is my head? What has happened to my head?

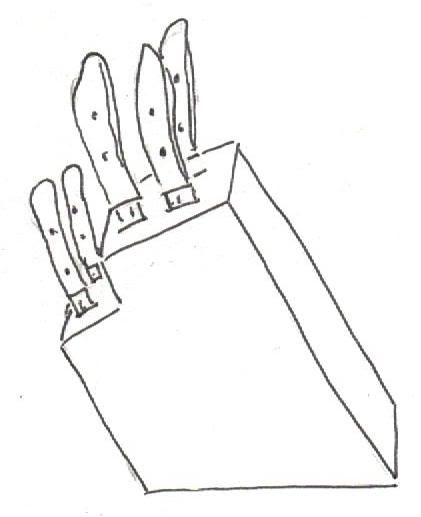

And now we are walking through the kitchen and my eyes catch the wooden knife holder. Oh God. Not that thought. But I can’t push it from my mind. It’s like a little demon voice in my head, telling me to stick that knife in my head. I could end all this pain.

In this ordinary kitchen in suburban America, my head and my heart scream like a dying bird in a cage.

I scare myself. Because my head is so fucked up from the Demerol and I don’t trust that thing in my head that keeps me from doing bad things, from going crazy, from sticking that knife in my head. Like there is a battle between that demon voice and another voice, and for the first time in my life I honestly don’t know which voice will win.

And now I am sitting on the couch by my mom and my head is screaming with craziness and it terrifies me and I want to cry but I cannot cry.

Like a child, I lay my head on my mom’s lap and she holds it like a mother. Oh mother. Can you stop this screaming in my head? How do I tell you all these awful things I feel and think? I want to jump up and get that kitchen knife and end this. This life. What keeps me from jumping up and getting that knife? The hands of my mother.

And something else. When the pain subsides a little, I go into my room and write a poem. It’s just a list of reasons not to die. A list of beautiful things. And it saves my life.

I’m in the backseat of my mom’s Dodge Stratus. We are driving down Brea Boulevard. We pass a succession of corporate retail stores: KFC, Starbucks, Burger King, Old Navy, Tower Records, Wal-Mart, McDonalds. And then the mall, with the big department stores signs: Macy’s, Robinson’s-May, Sears. And then Brea Boulevard turns into Brea Canyon Road, and it is only dry foothills and a two-lane road. Oil wells dot the landscape. Out the window, I notice three cows, grazing in sparse pastures beside the road. The cows are lean.

Suddenly we are in another town. The dry shrubs become palm trees and the sparse hills blossom into rows of tract housing and square office buildings. We are in Diamond Bar.

My mom pulls into the parking lot of one of these office buildings. The sides of the building are made of made of dark, reflective glass, and I can see my dark reflection approaching. It looks like another person.

Inside the building the fluorescent lights bother my eyes. We stop in front of a door which reads:

Leslie Carter, MFCC

Adult and Child Psychotherapy

I hate waiting rooms. This purgatory place filled with magazines, plastic plants, and framed prints.

We shake hands and follow her into her into a dimly lit office.

After all the getting to know you bullshit, Leslie asks my parents to describe what they have “observed” about my behavior and moods of late. My mom begins to speak and then starts crying.

“What kinds of emotions are you feeling lately?”

“I feel nothing. I’m totally numb, like emotionally. All I feel is this detachment.”

“Do you have this detached feeling now, at this moment?” Leslie asks.

“Yes.”

“And how intense would you say that it is?”

“It is very intense.”

Leslie writes something on a yellow legal pad.