I’m no math whiz or economist, but a very basic glance at the grower profits vs. worker wages in Charles C. Chapman’s orange groves in 1910 indicates astounding inequities.

In 1910, Chapman owned 500 acres of groves. According to U.S. Census data from that year, one acre would yield about 150 boxes of oranges. The average price for a box of valencias at that time was $2.25.

500 acres times 150 boxes times $2.25 per box equals $168,750 annual sales.

Let’s say Chapman took home half of that in pure profits (after deducting shipping costs, worker wages, etc.). That’s about $84,000. About $225 a day.

The average worker in Chapman’s groves made one to two dollars a day. A "good" worker could pick 100 boxes a day, which was worth $225.

So, by very conservative estimates, Charles C. Chapman was making 100-200 times what he was paying his workers. Is this fair? No. But American capitalism is not about fairness.

Chapman’s workers were often immigrants ineligible for US citizenship, and therefore unable to organize into unions, lest they be fired or deported. So they lived at the mercy of Mr. Chapman, who thought of himself as a very devout Christian. He planted the First Christian Church in Fullerton.

How could such obvious injustice and religious piety exist in the mind and heart of the same man? Historian/social critic Laura Gray Turner sheds light on this paradox:

“The Puritan/Protestant/Evangelical/American religious tradition that was shared by the emerging grower society was a complex blend of enlightenment philosophy, republican politics, democratic social theory, liberal economics, and a reliance on the Scriptures as the rule of life. Virtue was defined in negative terms with lists of prohibitions.”

This American tradition, of defining virtue in negative terms (don’t drink, don’t fornicate, don’t be gay) rather than positive terms (love your neighbor, be just and fair to everyone, pay your workers a decent wage) seems to linger today.

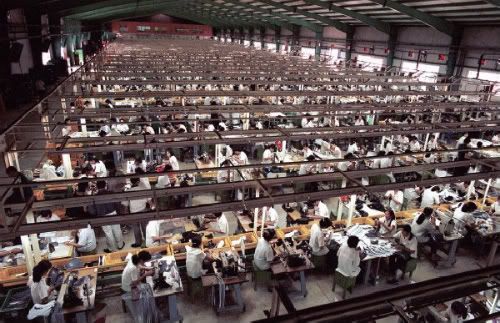

In today’s global market, American corporations often “outsource” their labor to countries with more “relaxed” labor laws. Thus, the CEO of Wal-Mart or Nike can make millions a year, while the worker in Indonesia who makes Wal-Mart or Nike shoes makes about one one-millionth of that. Not much has changed since the days of Chapman. If anything, things have gotten worse. The only solution I can see is for people to see that virtue has a place in business. You cannot separate your moral life and your business life.

Nike Sweatshop