Charles C. Chapman was Fullerton’s first mayor, and he has been called “The Father of the Citrus Industry.” He was hugely influential in shaping the early direction of Fullerton. But who was he? Where did he come from? What was he all about?

Apparently, he thought pretty highly of himself, because he wrote his own biography and called it Charles C. Chapman: The Career of a Creative Californian. Streets, schools, and a University were named after him. There is a giant bronze statue of him at Chapman University. One of Fullerton’s first newspaper editors called him “Czar Chapman.” And yet his entire wikipedia page is only two paragraphs. This is what it says:

Charles Clarke Chapman (1853–1944) was the first mayor of Fullerton, California and a relative of John Chapman, the legendary "Johnny Appleseed." He was a native of Illinois who had been a Chicago publisher before settling in Southern California.

Chapman was a supporter of the Disciples of Christ, who was a primary donor and fundraiser for California Christian College, which in 1934 changed its name to Chapman College, and is now Chapman University, in his honor.

I knew there had to be more than that. And there is..vastly more. In the Local History Room of the Fullerton Public Library I found a Master’s thesis entitled “Citrus Culture,” by Laura Gray Turner. There is an entire section entitled “Charles C. Chapman: Determined Agriculturalist and Rancher Elite” which tells the fascinating and disturbing story of this man.

Charles Clarke Chapman was born in Macomb, Illinois in 1853, into a culture and family charcterized by “a hardy protestantism, fundamental in doctrine, puritanical in tradition, and capitalistic in economic dogma.” These combined values of fundamentalist Christianity and capitalist zeal would drive the future career of Charles C. Chapman.

After a series of economic ventures and failures, Chapman entered the history business in 1876, at age 23. Chapman and his brothers founded Chapman Brothers, Printers and Publishers and they began writing and printing local history books. What sort of history did he write and publish? According to Turner, they were, like much amateur history of the era “celebrations of Anglo-Saxon origins. Individuals accorded grandest adulation in these volumes were the successful businessman, the manufacturer, and especially the hardworking farmer.” These 19th century amateur histories were often informed by what historian John Higham calls “nativist tradition fostered by an attitude of racial superiority.”

This celebration was made manifest by the 1893 “World’s Columbian Exposition” in Chicago, a massive fair “in celebration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage.” The fair grounds were called, appropriately, “White City.”

This fair lasted six months, attracted some 27 million visitors (about half of the U.S. population) and was spread out over 633 acres. Because of its size, this Exposition “shaped the way the nation saw itself and the world…[it was] a kind of tract, an argument for the superiority of our civilization…It saw itself as American destiny made manifest.”

Charles C. Chapman was intensely involved in this exhibition. He and his brothers, “always ready to seize an opportunity for profit, made plans for the construction of several hostelries [and]…an eight story luxury hotel.” I guess their history business had paid off.

Chapman described the World’s Columbian Exhibition as “the most stupendous and beautiful display ever made of the world’s achievements in art, industry, architecture, soil products, science, religion, and in the whole realm of man’s accomplishments.” Social critic Edward Bellamy, author of the classic Looking Back saw the Exhibition quite differently: “The underlying motive of the whole exhibition, under a sham pretense of patriotism is business, advertising with a view to individual money-making.”

Charles Chapman did indeed make a lot of money off the Exhibition, but his fortunes were short-lived. In 1893, the United States plunged into an economic depression, in which Chapman lost almost everything. In 1894, his wife died. Turner writes, “Resolutely, Chapman turned his face westward, where now at mid-life he would begin anew.”

To hear about Charles Chapman’s adventures in Orange County, tune in next time. Same Bat Time, same Bat Channel! (That is a reference to the 1960s television program Batman)

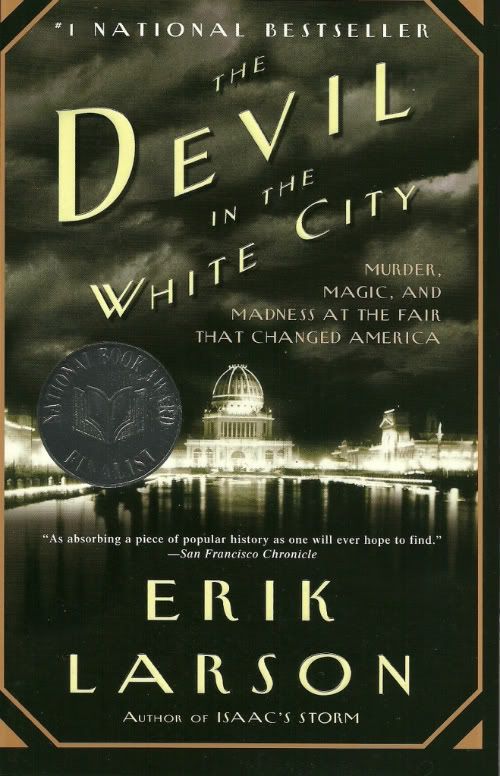

Apparently, there is a whole book about the 1893 World's Columbian Exhibition. Check it out!