“Your coming is as the footsteps of doom. You bring great evil here.”

--The Lord of the Rings

One interesting aspect of American history is that the economy has almost collapsed a number of times. With economic downturn come strikes and social unrest. But always, without fail, a wealthy elite manages to reclaim power and “set things right.”

So it was with the great economic crash of 1893. Charles C. Chapman, wealthy publisher and property owner, lost almost everything. So he packed up and headed west from Chicago, seeking new markets. And he found them in the fields of Orange County.

Reading Laura Gray Turner’s account of Chapman’s rise to power in Southern California, I couldn’t help but think of the movie “There Will Be Blood.” Like the oil tycoon Daniel Plainview, Charles Chapman was possessed by a single-minded focus and obsession with making money, and lots of it. Turner writes, “With characteristic industry, Chapman applied his indefatigable discipline and business savvy to the task of restoring profitability to his newly acquired and rechristened Santa Ysabel Ranch.”

He studied handbooks of citriculture, met regularly with other local growers, and established “contacts among the nation’s financial, commercial, and political power brokers.”

Like most business endeavors, Chapman’s early years as an orange rancher were met with limited success and sometimes outright failure. Pests and disease among the trees proved major obstacles. He experimented with fumigation methods, sometimes using cyanide to kill pests, which for a time was common practice. Cyanide is a deadly poison that kills insects, but isn’t too good for people either.

But Chapman’s real challenge was competition with other local growers. He needed an edge, and he found this edge with clever marketing and branding, relatively new business practices, but ones that would transform American consumer culture in the 20th century.

Drawing upon his advertising and publishing experience, Chapman elevated the orange crate label to an artform which used “vivid symbols and scenes, careful constructs of fact and fantasy, [which] evoked memory and anticipation in a contrived assault upon the senses.”

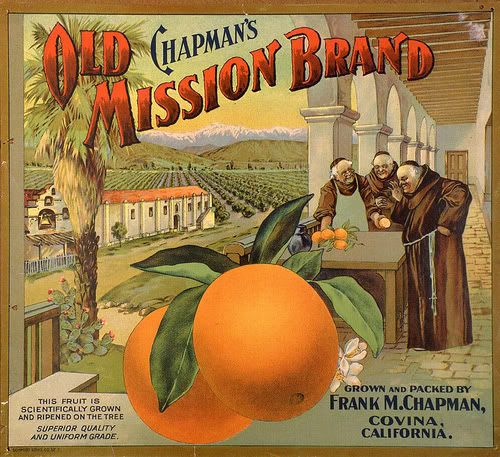

Chapman was a pioneer of the idea that consumers do not just buy products, they buy ideas, they buy fantasies. And that is what Chapman’s Old Mission and Golden Eagle orange brands created. The images on Chapman’s Old Mission brand labels offered a “sanitized vision of the Spanish past…the mission myth of paternalistic displacement by a superior culture…an Anglo-Saxon approbation of the Spanish mission heritage.” The Old Mission labels featured peaceful padres in a pristine California utopia, a fantasy totally disconnected from California’s real history, which was full of violence, conquest, racism, and oppression.

Conspicuously absent on the Old Mission or Golden Eagle labels were “the ranks of workers whose backs and hands plowed, planted, watered, picked, and packed the fruit on its way to consumers’ lips.” The exploited masses whose labor made the citrus industry profitable (Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans) were not a part of Chapman’s advertising fantasy world.

But it was the unacknowledged labor of these masses who made Chapman the business and political titan he became. It was their backs who bore him into the Mayor’s seat, into the ranks of the Republican power elite, who might have carried him into the White House. Calvin Coolidge and the Republican Party wanted Chapman to be their Vice Presidential candidate in the 1920s, but Chapman declined, preferring instead to reign over his Southern California business and political empire.