The following is from a work-in-progress called The Qur'an: a Book Report, in which I read each surah of the Qur'an and write about what I learn.

This is another Meccan surah which (yet again) warns the unbelievers about the coming Day of Resurrection--when they will be judged and sent to either heaven or hell. By now, this is a very familiar message.

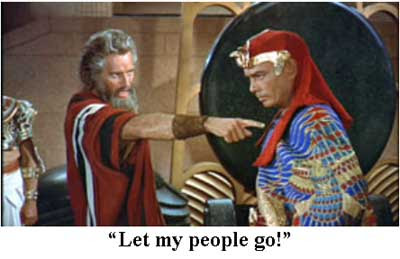

What is interesting, to me, about this surah is how it re-imagines a story about Moses and Pharaoh to support its message. In the original story of Moses and Pharaoh, found in the book of Exodus in the Jewish Torah (and the Christian Old Testament), God sent Moses to Pharaoh with a very specific message and mission. As Charleton Heston put it in The Ten Commandments: "Let my people go!" Moses demanded that Pharaoh free all the Israelite slaves in Egypt so they could form their own nation in the "Promised Land."

In this Qur'anic version of the story, however, no mention is made of the Israelite slaves, let alone their hopes for nationhood. In this version, Moses' mission is not Jewish emancipation, but rather the salvation of Pharaoh. Moses tries to convert Pharaoh to monotheism, saying: "Do you want to purify yourself [of sin]? Do you want me to guide you to your Lord, so that you may hold Him in awe?" Of course, Pharaoh refuses to abandon a millennia of Egyptian religious tradition, and so he suffers devastation. Thus, what was originally a story about Jewish national liberation becomes, in the Qur'an, a warning about the danger of unbelief.

What's interesting to me about this surah is not trying to figure out which story of Moses and Pharaoh is the historically "correct" version. After all, modern archeologists like Israel Finkelstein have concluded that the Exodus (at least as its described in the Book of Exodus) probably never happened. What's interesting to me is how a common story, or legend, like the story of Moses and Pharaoh, can be re-imagined by different religious communities for very different purposes. Myths, legends, and sacred history are more malleable than we think. How we interpret them says more about us than it does about the story.