The Movies Are Born in France

The first movie ever was screened in Paris in 1895 by two brothers: Auguste and Louis Lumiere, who had invented the first movie-making camera and projector. They made over 1,400 short documentary films, and traveled the world, exhibiting their miraculous new invention in places as diverse as India, Iran, and Mexico. Soon others would develop the technology, and the fledgling global film industry was born. A rival of the Lumiere brothers was Georges Melies, whose magical fantasy films included the famous A Trip to the Moon...

1.) A Trip to the Moon (La Voyage dans La Lune) directed by Georges Melies (1902). One of the first films ever made, this science fiction spectacle follows the adventure of travelers from the earth, who fly to the moon in a cannon-powered craft. This film is astonishing for its use of (obviously pre-digital) special effects and lavish theatrical sets.

2.) Les Vampires (serial) directed by Louis Feuillade (1915). This was a popular film serial, released in ten episodes, which follows a journalist and his friend who try to uncover and stop a gang known as The Vampires. There are no actual vampires in this film. It’s just the name of the gang. Feuillade is also known for the popular crime serials Famtomas and Judex which, together with Les Vampires, form a kind of trilogy.

Paris in the 1920s: Surrealism and other Experiments

Paris in the 1920s was a haven for artists, writers, and filmmakers from around the world. Here are some of the films made during this time period...

3.) The Passion of Joan of Arc (La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc) directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer (1928). Based on the actual trial record of French military leader Joan of Arc when she was a captive in England, this film is known for its beautiful cinematography and for Renee Jeanne Falconetti's haunting performance in the title role.

4.) Queen of Atlantis (L'Atlantide) directed by Jacques Feyder (1921). Based on the best-selling novel by Pierre Benoit, this film tells the story of two French officers who, in 1911, become lost in the Sahara desert and stumble upon the legendary kingdom of Atlantis, ruled by the ageless queen Antinea. Love, jealousy, and violence ensue.

Jean Renoir and the Golden Age of French Cinema

Son of the influential impressionist painter Auguste Renoir, Jean Renoir made a number of really important French films, which combined a kind of "poetic realism" and radically liberal social ideas. Renoir's films explore changing social realities in France leading up to, during, and following the shattering events of World War II. Here are three of his most significant films...

6.) Boudu Saved From Drowning (Boudu Sauve des Eaux) directed by Jean Renoir (1932). An early masterpiece by the hugely influential French director Jean Renoir, this film follows a homeless man (Boudu) who is saved from drowning by a middle class bookshop owner, who allows Boudu to live with his family. Hilarious antics ensue, which call into question bourgeois (middle class) values prominent in France at the time.

7.) The Grand Illusion (La Grande Illusion) directed by Jean Renoir (1937). The Grand Illusion is one of the greatest anti-war movies ever made, from a director who spent his career courageously and poetically causing viewers to question prevailing cultural attitudes and prejudices. Set in a German prisoner-of-war camp during the First World War, this film contains no villains save the war itself, and contains moving friendships between supposed "enemies."

8.) The Rules of the Game (La Regle du Jeu) directed by Jean Renoir (1939). Generally regarded as one of the greatest films ever made, this film satirizes social classes in France on the eve of World War II. Renoir's poetic depiction of class arrogance/callousness feels relevant even today. The term "poetic realism" is often used to describe Renoir's sensibilities as a filmmaker.

9.) L'Atalante directed by Jean Vigo (1934). The film follows the marriage of a river boat captain and a girl from a small town. The couple live aboard a boat called L'Atalante along with a crusty old sailor namd Pere Jules and a cabin boy. The film is famous for its poetic depiction of erotic love. Martha Nochimson, author of World on Film writes, "The symbolism of L'Atalante is muted by the visual poetry that radiates from Vigo's delight in the abundance of natural pleasures in the world."

The Impact of World War II on French Cinema

It's hard to overstate the devastating and traumatic effect that World War II had on France. From 1938-1945, France was occupied by the fascist government of Hitler's Nazi Germany. This was, needless to say, a major setback for the film industry, and for artists in general. Some filmmakers like Jean Renoir, escaped to the United States. Others lived under an oppressive and violent regime. After the war, France continued to experience political turmoil as it attempted to restore its government and society.

10.) Children of Paradise (Les Enfants du Paradis) directed by Marcel Carne (1945). Filmed under the near-impossible conditions of the German occupation of France during World War II, the film is actually set during the 1830s theater scene in Paris. It follows the relationship of a woman named Garance and the four men who court her: an actor, a criminal, an aristocrat, and a mime artist, her true love. Challenging both gender and social mores, the film is about the struggle of the individual spirit against a dangerous, mob-like society. It is also, indirectly, about the social trauma caused by World War II. In 1995, the film was voted "Best Film Ever" by a poll of 600 French film critics and professionals.

11.) Diary of a Country Priest (Journal d'un Cure de Campagne) directed by Robert Bresson (1951). A good example of a postwar film that does away with opulence in favor of austere, monastic spiritualism, Diary of a Country Priest tells the story of a troubled, sickly priest who is sent to his first parish assignment. There he is badly treated, even mocked by his parishioners. The film explores the renunciation of worldly pleasures, in stark contrast to the prewar films of Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo, which celebrated them. Two famous lines from this film are "God is not a torturer" and "All is grace." This is a powerful film, especially in light of the devastation (both physically and spiritually) that France suffered during World War II.

12.) The Wages of Fear (La Saliare de la Peur) directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot. Set in a small, South American town dominated by an American oil company, the film follows four expatriates from Europe as they drive a truck loaded with nitroglycerine over a rocky landscape to extinguish an oil fire. The film is a nail-biting thriller, and filled with post World War II existentialist dread and despair. It also serves as a brutal condemnation of US corporate exploitation of Latin America. A famous quote is "If there's oil around, they're not far behind," referring to Americans.

13.) The Big Day (Jour de Fete) directed by Jacques Tati (1949). Made by the great comic director/star Jacques Tati, the film follows a distracted bicycle-riding mailman who, upon learning about the United States' rapid-transit mail system, tries hilariously to speed up his service. The film introduces a central theme of Tati's work, which is to use humor to criticize western society's over-reliance on technology to solve its (perceived) problems.

14.) Mr. Hulot's Holiday (Les Vacances de M. Hulot) directed by Jacques Tati (1953). This is the first of four films to feature the character of Mr. Hulot (played by Tati), a lovable, pipe-smoking Frenchman whose misadventures poke fun at modern society. In this film, Mr. Hulot takes a seaside holiday where he encounters various characters locked into their perceived social roles.

The Imagination of Jean Cocteau

Perhaps the most unique director of the postwar period, Jean Cocteau was an auteur who made highly personal films which used mythology and fantasy to delve deeply into the problems and dysfuntions of modern life.

15.) Beauty and the Beast (La Belle et La Bete) directed by Jean Cocteau (1946). A live-action adaptation of the famous fairy tale, shot through with Cocteau's lyrical cinematic style.

16.) Orpheus (Orphee) directed by Jean Cocteau (1950). An modern adaptation of the Greek myth of a musician who rescued his wife from the underworld, only to lose her in the end. This film uses mythology to explore very real psychological conditions. The film envisions "hell" as a bombed-out European city ruled by bureaucrats in suits. A poetic meditation on art, war, love, and death--Cocteau's Orpheus is a gem of world cinema.

17.) Testament of Orpheus (Le Testament d'Orphee) directed by Jean Cocteau (1960). A cinematic sequel/dialogue with his film Orpheus, this film was written by, directed by, and stars Cocteau in true auteur form. The film mixes fantasy elements with reality and plays with space and time to create a profound meditation on the psyche of an artist.

The New Wave

After World War II, the French government provided funding for a national cinema. In order to receive this funding, some directors opted to adapt old, classical literature. Another group of emerging critics and filmmakers reacted passionately against what they perceived as backward-looking films that were not relevant to modern life. These were mainly young critics who wrote scathing articles for the influential magazine Cahiers du Cinema, including Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut. These directors began making low-budget but highly creative films, and thus began what became called the New Wave, which permanently changed the direction of cinema.

18.) Handsome Serge (Le Beau Serge) directed by Claude Chabrol (1959). Generally considered to be the first feature length New Wave film, Le Beau Serge follows the lives of two unhappy young men in a small town.

19.) Paris Belongs To Us (Paris Nous Appartient) directed by Jacques Rivette (1960). The plot focuses on a group of actors in Paris who are rehearsing a Shakespeare play that will never be performed. The film is really about bohemian life in late 1950s Paris, with all its anxiety and disillusionment. It features cameos by fellow New Wave directors Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, and Jacques Demy. Rivette, like many New Wave directors, was also an important film critic for the influential magazine Cahiers du Cinema.

20.) My Night at Maud's (Ma Nuit Chez Maud) directed by Eric Rohmer (1969). Part of a sextilogy (six film series) known as Six Moral Tales, My Night at Maud's focuses on an extended conversation between a Catholic (Jean-Louis), a Marxist (Vidal), and a libertine (Maud), as they discuss religion, atheism, love, morality, and the writings of French mathematician/philosopher Blaise Pascal.

21.) Breathless (A Bout de Souffle) directed by Jean-Luc Godard (1960). Perhaps the most famous of the New Wave films, Breathless made innovative use of filming techniques like "jump cuts," and it presented a new kind of protagonist, the anti-hero who flaunts the conventions of society in shocking and often absurd ways. The lives of the characters seem ruled by chance, as opposed to any conventional form of conventional narrative. People betray one another for no apparent reason, they die unexpectedly and unheroically. In this way, the New Wave films sought to portray a more realistic vision of life.

22.) Hiroshima, My Love (Hiroshima, Mon Amour) directed by Alain Resnais (1959). Follows a brief but intense relationship between a French actress and a Japanese architect who meet in the town upon which the United States dropped the atomic bomb, the film uses innovative flashback sequences to poetically explore the memory and trauma of war.

23.) The 400 Blows (Les Quatre Cents Coups) directed by Francois Truffaut (1959). This was the first feature in the prolific career of Francois Truffaut, probably the second most famous New Wave director (after Godard). It follows the life of Antoine Doinel, a character based loosely on Truffaut himself. In this film, he is an adolescent. The director would, throughout his career, make three more films featuring this character as he goes through the ups and downs of life.

24.) Jules and Jim (Jules et Jim) directed by Francois Truffaut (1962). Set during World War I, the film follows a love triangle between a bohemian Frenchman (Jim), his shy Austrian friend (Jules), and the woman they love (Catherine). The film is about people seeking radical freedom, with all its joys and consequences.

25.) Cleo from 5 to 7 (Cleo de 5 a 7) directed by Agnes Varda (1962). There were not many female directors associated with the French New Wave, but Agnes Varda is a powerful exception to the generally male-dominated milieu. The film follows a beautiful French singer as she awaits the diagnosis from her doctor, who will tell her if she has cancer or not. In her existentialist crisis, Cleo is forced to deal more honestly with her life, her lover, and fundamental questions of identity, beauty, and selfhood. She has a brief but powerful conversation with a French soldier who is about to be deployed to Algeria. Thus, in a sense, both stand together at the precipice to the abyss of death and oblivion, and both learn to take solace in their shared condition.

Jean-Luc Godard, the Mad Genius of French Cinema

The inspiration for this new curriculum is the Hibbleton Gallery film series, which my friend Steve Elkins and I have been hosting for the past couple years. Each month, we curate films based on a region, a director, or a theme. One of Steve's all-time favorite directors is Jean-Luc Godard, who became really famous as a New Wave auteur, but then kept right on making a LOT of really challenging films, and he continues to make films today, in his 80s. His latest feature, Goodbye to Language (in 3-D!) came out last year. I would like to include the Godard films we showed during the film series, along with Steve's descriptions of them:

26.) "A Woman Is A Woman" (1961): After changing movies forever with his debut "Breathless," then receiving threats of expulsion and death from the French government for making a film that exposed their official policy of torture in Algeria ("Le Petit Soldat"), Godard made this radical musical comedy, an explosion of cinematic creativity that even today feels ahead of its time. It was "a reaction against anything that wasn't done," Godard said, "It went along with my desire to show that nothing was off-limits. An Inquisition-like regime ruled over French cinema. There were taboos and laws and I wanted to show that it all meant nothing. French cinema is dying under the weight of false myths. The myths had to be destroyed for French cinema to be reborn."

27.) "Vivre Sa Vie" (My Life To Live, 1962): An argument with philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre that doubled as a love letter to Godard’s wife Anna Karina. A hallmark of Sartre's philosophy was the idea that a person is defined by his actions, his outward reality, and that belief in an essence distinct from public and social phenomena was unfounded. Since the early 1950s, Godard had been arguing that Sartre's opposition of outer existence and inner essence was fallacious because it was transcended and resolved in the cinema, which shows how the collision of light with the surface of the world reveals inner and metaphysical qualities. "My Life To Live" examines the relationship between surface and meaning by following "a pretty Paris shopgirl (Godard's wife, Karina) who sells her body but keeps her soul." "I want to prove that existentialism presupposes essence, and vice versa," said Godard, "and that this in itself is something quite beautiful."

28.) "Pierrot Le Fou" (1965): Jean-Luc Godard on his film Pierrot Le Fou: "You say 'let's talk about Pierrot.' I say, 'What is there to say about it?' ...If you wake the woman you love in the night, you don't telephone your friends to tell them about it afterwards. Difficult, you see, to talk about cinema...because life is its subject, with scope and colour as its attributes...life itself which I wanted to make so much of so that it would be wondered at...the only great problem with cinema seems to me more and more with each film when and why to start a shot and when and why to end it. Life, in other words, fills the screen as a tap fills a bath, which is simultaneously emptying at the same rate at the same time. It passes, and the memory which it leaves us is in its own image...this double movement, which projects us towards others while taking us inside ourselves, physically defines the cinema...Celine, let's leave him to literature...suffering and piling book upon book amid the regiments of language, we, with the cinema, are something else, life first of all, which isn't new, but difficult to speak of, one can barely live it and die, but speak of it, well, there are books, but in the cinema, we have no books, we have only music and painting, and even those, as you know, can be lived but rarely spoken."

29.) "Masculin Féminin" (1966): A film about youth and sex in France in 1965, on the eve of legalizing contraceptives for women which had been banned since 1920. The first direct vote for a French head of state since 1848 was about to be determined by the youth of France who wanted "the pill," prompting Godard to make this sociological study of the new generation he called "the children of Marx and Coca-Cola." "The class struggle is no longer the same as we were taught in books," Godard observed, "it's true that Bob Dylan is a link between the yé-yé kids and politics, a way to bring the two together. But, you know, I think it was Baudelaire who said that it was on the toilet walls that you see the human soul: you see graffiti there - politics and sex. Well, that's what my film is."

30.) "Alphaville" (1965): A cockeyed fusion of science fiction, surrealist poetry, and pulp detective noir starring a computer obsessed with Jorge Luis Borges, "Alphaville" (originally titled "Tarzan vs. IBM") emerged from Jean-Luc Godard's conversations with cybernetics and artificial intelligence researchers in the early 60s to understand "to what extent electronic brains and the calculation of probabilities are becoming important in the lives of businessmen and heads of state" to create a society in which "people should not ask 'why', but only say 'because'." "Alphaville" is also perhaps the only science-fiction film ever made without a single set or special effect. Instead, Godard developed his own guerilla filmmaking methods on the streets of Paris (causing his cinematographer to exclaim: "He'd like to swallow the film and process it out his ass") to place an X-ray on contemporary life, art, political theory, and love, to expose "the future" as a veiled inner reality of the present.

31.) "La Chinoise" (1967): Documents a semi-fictional Maoist cell at Nanterre University working through their first steps toward "changing reality." The film is widely understood as prophetic: less than a year after it's release, almost a million people marched in Paris to denounce the French government, occupied the universities and police stations, set fire to the Paris stock market, while strikes spread all over France, factories were taken over by their workers, theaters were turned into public forums where people from all walks of life could finally speak, and the flow of gasoline to the capital was stopped, causing Godard to remember Paris that month as "a moment where one heard the sound of pedestrians in the street simply because there was no more gasoline.”

32.) "Weekend" (1967): In the final years of the ‘60s, Jean-Luc Godard made a string of explosive films that attempted to encapsulate the global revolutions taking place in a new language adequate to them. “Weekend” shows the Apocalypse of Western civilization as an endless traffic jam of crashed cars and planes (filmed as if it were modern sculpture), “Sympathy For The Devil” contrasts the incommensurable realities of The Rolling Stones and the Black Panthers, and “Le Gai Savoir” attempts to entirely deconstruct human language and the blitzkrieg of media signals we’re bombarded with, to rebuild them on stronger foundations.

33.) "2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her" (1967): In the mid-1960s, Charles de Gaulle began restructuring French society to become modeled on American consumer culture. One of the costs of this development was that some middle class housewives in Paris had to become prostitutes to afford the newfound "necessities" of living. In outraged reaction, Jean-Luc Godard made "2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her," an anthropology of the Americanization of Paris, which considers the transition to "modern living" as a gradual collective prostitution of the mind. In this remarkably beautiful and dense film, Godard places a microscope on the structure of our daily lives, colliding the veiled inner meanings of words and objects with dazzling speed, resulting in mind-bending insights into the invisible borders that define us, from the macro (“Where does the individual end and society begin?”) to the micro (“Where does the material end and the spirit begin?”). Features the classic scene where a swirling cup of espresso becomes the formation of consciousness and the universe.

34.) "Le Gai Savoir" (1968): "It was not going to be possible to make the new cinema by using the language of the old," wrote James Monaco about "Le Gai Savoir" in 1975. "Having returned to zero, Godard had to start over again. LE GAI SAVOIR is the first step. It is Godard’s ultimate effort at 'semioclasm,'(1) the name critic Roland Barthes gave to the necessary job of breaking down the signs of the languages we take for granted in order to rebuild them on stronger foundations. Its aim is nothing less than the beginning of a rigorous examination of the systems of signs through which and by means of which politics, love, beauty, and existence are expressed and understood. 'What is really at stake,' Patricia discovers, 'is one’s image of oneself.'

35.) Cinétracts (1968): Godard breaks into the Centre du Cinema and steals their cameras to distribute them amongst rioters on the streets of Paris during the cataclysmic upheavals of May '68. He and Chris Marker (in collaboration with Alain Resnais and other luminaries of French cinema) create a new form of DIY cinema called Cinétracts, which were edited in-camera on single rolls of cheap 16mm film no longer than 2 to 4 minutes each, and released to the public anonymously. Anticipating the effects of the digital revolution by several decades, this allowed Godard to work entirely outside of the studio filmmaking system and chains of theatrical distribution, eliminate hierarchies and power imbalances from the filmmaking process (theoretically), and deal with events on the streets as they were happening. They often contained still photographs with hand-scrawled words added.

37.) "Numéro Deux" (1975): In the early 1970s, Godard turned from both traditional theatrical distribution and the supremacy of large-format film by making DIY films shot mostly on portable 16mm and video. By 1975 and Numéro Deux, Godard was already using video as an aesthetic and philosophical tool to be pondered, tested and abused, anticipating the digital revolution by several decades, and allowing him to work as a guerilla filmmaker completely outside French film industry. It also placed all means of production, distribution, and exhibition within his own hands. In one of his most radical works from this period, "Numéro Deux," the entire movie takes place on two television screens within the film frame. Godard procured funding for the film by saying it would be a remake of his first film "Breathless", which he never actually intended to do. "Numéro Deux" is an examination of sexual economy within the family and the relationship between media (films, factories, print, video) and the human body.

38.) "Ici Et Ailleurs" (1976): Initially intended to be a documentary about the Palestinian armed struggle (shot in Lebanon, Jordan, and the West Bank between 1970 and 1974), Godard transformed his footage into a breathtaking meditation on how each of us develops our sense of truth, history, and our political worldview. A searing analysis of how our perceptions of ourselves and others are sculpted from our relationship to images and texts, those slippery slopes upon which our understanding of history (and other fictions) is recorded and handed down to us, the film has perhaps never been more relevant than now, in the age of Facebook and the internet.

39.) "King Lear" (1987): Godard's 1987 avant-garde "adaptation" of Shakespeare starring Woody Allen, Molly Ringwald, and Norman Mailer! A late descendant of Shakespeare attempts to restore his plays in a world rebuilding itself after the Chernobyl catastrophe. Godard himself plays Professor Pluggy, an eccentric with video cables for hair who is obsessed with Xeroxing his own hand.

40.) "Helas Pour Moi" (1993): Jean-Luc Godard's rumination on the meaning of all creation, from God to Bruce Willis movies, set to the music of Arvo Pärt and Keith Jarrett. The film explores the transmission of the sacred across time, through a surrealistic, modern take on the Greek myth of Amphitryon, where Zeus (played here by Gerard Depardieu!) descends to earth to seduce a woman by disguising himself as her husband. A gorgeous meditation on the idea of Incarnation, the penetration of the divine in love, art, language, and history, described by Godard as his attempt to "see the invisible...the other half of the universe beyond images and beyond stories."

41.) "Je Vous Salue, Sarajevo" (1993): Culture is the rule, and art is the exception. Eveybody speaks the rule: cigarette, computer, T-shirt, TV, tourism, war. Nobody speaks the exception. It isn't spoken, it's written: Flaubert, Dostoyevski. It's composed: Gershwin, Mozart. It's painted: Cézanne, Vermeer. It's filmed: Antonioni, Vigo. Or it's lived, and then it's the art of living Srebrenica, Mostar, Sarajevo. The rule is to want the death of the exception.

42.) "Histoire(s) du Cinema" (1988 - 1998): Though few have seen it, the ones who have tend to consider this to be Godard's magnum opus, arguably one of the most important contributions to the humanities (in any medium) of the 20th century. Facing the deceptively simple question "What was cinema?", Godard develops a highly theological and realistically mystical philosophy of history, spun in the densely textured poetic style of "Finnegan's Wake" and the Cantos of Ezra Pound, which seeks to demonstrate how our personal relationship to projections of flickering light creates (rather than reflects) the world we live in, directly impacting the social and political realities of people in far away places we never see. Nearly five hours long, with 200 hours of footnotes planned for it's encyclopedic knowledge of seemingly everything.

43.) "The Old Place" (1998): Today, you don't see the image, you see what the title says about it. It's modern advertising. This image that you are, that I am, which Walter Benjamin speaks of, of that point where the past resonates with the present for a split second to form a constellation. "The work of art," he says, "is the sole apparition of something distant, however close it may be." The origin is both what is discovered as absolutely new and what recognizes itself as having existed forever. Between the infinitely small and the infinitely large we'll eventually find an average. And the average will be the average person, no doubt. Artistic thinking begins with the invention of a possible world, then using experience and work, painting, writing, filming, to confront it with the outside world. This endless dialogue between imagination and work allows for the formation of an ever-clearer representation of what we agree to call reality. 19 people attended the Crucifixion, 1,400 the first performance of "Hamlet" and two and a half billion attended the World Cup final. In the immensity of the universe, can time be recounted? Time as it is, as such and in itself? Art wasn't protected from time. It was what protected time. We work in the dark, we do what we can, we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. Maybe we're the ghosts of people taken away when everybody vanished.

44.) "De L'Origine Du XXIe Siècle" (2000): The spirit borrows from matter the perceptions it draws its nourishment from, and gives them back as movement stamped with its freedom. Nothing conflicts with the image of the beloved more than that of the state. The state's rationale directly opposes the sovereign value of love. The state in no way possesses, or else it has lost, the power to embrace, before our eyes, the totality of the world, that totality of the universe offered externally via the loved one as object, and internally via the lover as subject.

45.) "In Praise Of Love" (2001): "The measure of love is to love without measure."

-St. Augustine

46.) "Liberté et Patrie" (2002): Trying to see something. Trying to picture something. In the first case, you say, "Look right there." And in the second, "Close your eyes." What's the best way of knowing if someone is trustworthy? You ask him, "What have you read?" If he answers, Homer, Shakespeare, Balzac, then he is not trustworthy. But if he answers, "Depends what you mean by reading", then there's hope. The eyes are freedom, the hands are fatherland. What does the wind do when it's not blowing? The sun is an example of the supremely sensitive being, because it can always disappear. O universal time when nothing was mute for the eyes of a child.

47.) "Notre Musique" (2004): One of my top three favorite films of all time, a triptych that sets Dante's three Kingdoms of the afterlife in the modern world, in which Heaven is a beach guarded by US Marines and Purgatory is a (real) congregation of the world's great poets in the ruins of the Sarajevo library, where two million books (and people) had just been destroyed in a bombing. As they begin one of the most moving discussions ever captured on film about the complexities of forgiveness, we follow the parallel stories of two Israeli women propelled by these reflections in opposite directions: one toward martyrdom and the other toward perceiving the face of her "enemies" as the outline of the Absolute, the geography of the Infinite which traces "where God passes." Inspired by the thought of Martin Buber, Hannah Arendt, José Lezama Lima, and Emmanuel Lévinas, "Notre Musique" is a profound work of theology that considers whether heaven and hell are in fact the same place: both "protected" by a divide across which we cannot embrace "the Other," who is our mirror. Featuring Arab poet Mahmoud Darwish.

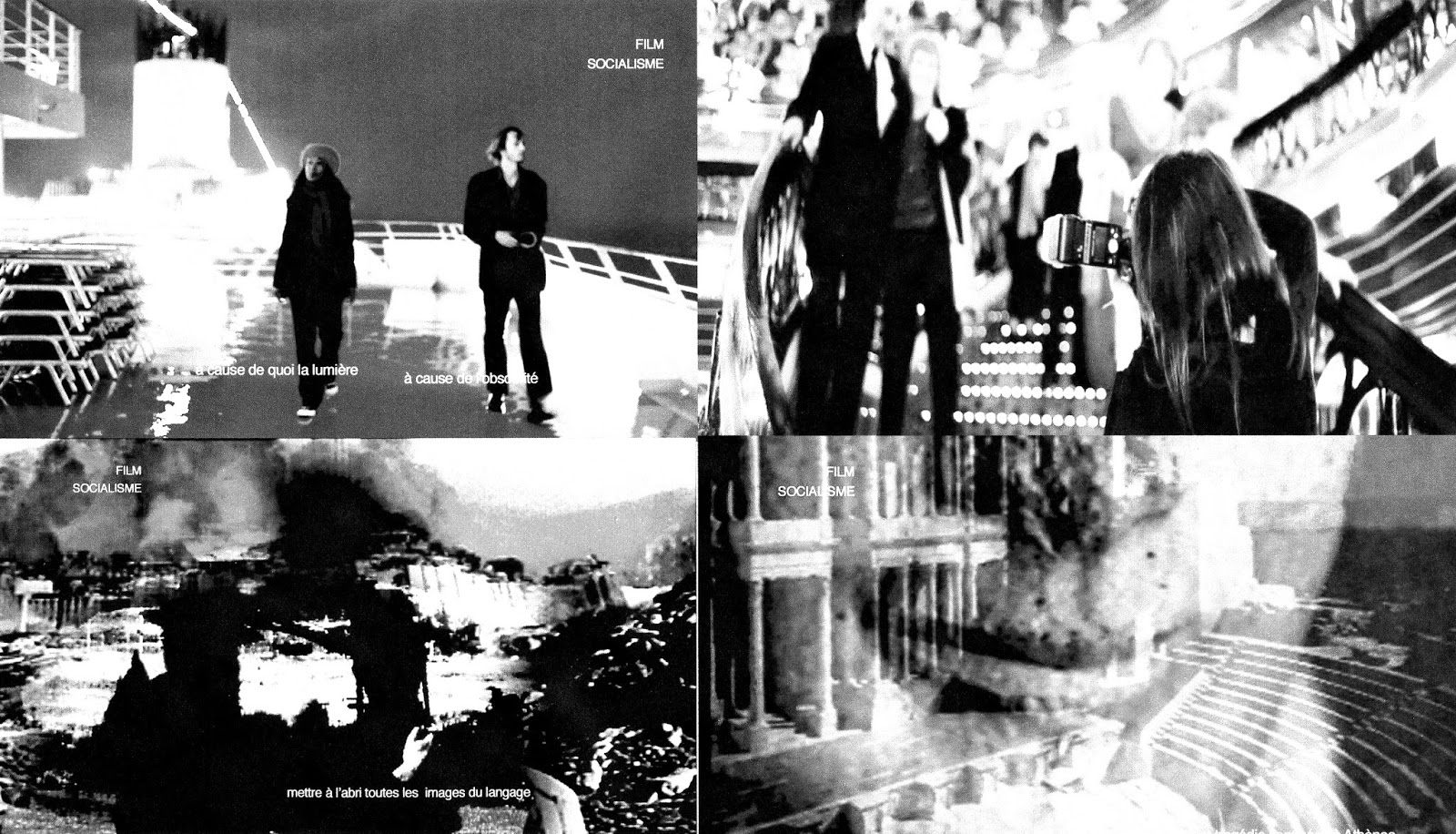

48.) "Film Socialisme" (2010): We concluded Hibbleton Gallery's two-month Jean-Luc Godard Retrospective with a discussion of his current activities building his own homemade 3D movie camera at the age of 85 which he used to shoot his first 3D feature "Goodbye To Language," prior to a screening of "Film Socialisme" (2010), Godard's first work shot entirely on digital and cell phones, in which modern day tourists (including Patti Smith!) take a cruise ship through the sites of "our humanities" (Egypt, Palestine, Odessa, Greece, Naples, and Barcelona). Said to have anticipated the Greek debt crisis and the Arab spring, an encyclopedic illumination of the complex mythologies under which we all live, from the origins of modern civilization to cell phones, from Old Testament Israel to Youtube cat videos, from aerobics to globalization, from the conflict between universalist ideals and national origins to the tension between humanism and the enduring particularisms of ethnicity and historical memory.

Beyond the New Wave

49.) One Sings, The Other Doesn't directed by Agnes Varda (1977). Focuses on the lives of two women against the backdrop of the Women’s Movement in 1970s France.

50.) Diva directed by Jean-Jacques Beneix (1982). One of the first French films to let go of the realist mood of 1970s French cinema and return to a colourful, melodic style, later described as “cinema du look”. Young postman Jules is obsessed with Cynthia Hawkins, a beautiful and celebrated opera singer who has never had a performance of hers recorded. He attends her performance, secretly and illegally records it, which sets the plot on motion. In the film's final scene Jules plays his tape of Cynthia's performance for her and she expresses her nervousness over hearing it, as she "never heard [herself] sing."

51.) Love at First Sight (Coup de Foudre, aka Entre Nous) directed by Diane Kury (1983). Set in the France of the mid twentieth century, the film tells the story of two young married women in the 1950s who don't recognize how unfulfilled they have been in their marriages until they meet each other. They develop an intimacy that is based partly on their boredom with their domestic situations.

52.) Jeanne Dielman: 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles directed by Chantal Akerman (1985). Upon the film's release, The New York Times called Jeanne Dielman the "first masterpiece of the feminine in the history of the cinema". Chantal Akerman scholar Ivone Margulies says the picture is a filmic paradigm for uniting feminism and anti-illusionism. The film was named the 19th-greatest film of the 20th century by The Village Voice. Jeanne Dielman examines a single mother's regimented schedule of cooking, cleaning and mothering over three days. The mother, Jeanne Dielman, prostitutes herself to a male client daily for her and her son's subsistence. Like her other activities, Jeanne's prostitution is part of the routine she performs every day by rote and is uneventful. But on the second day, Jeanne's routine begins to unravel subtly, as she drops a newly washed spoon and overcooks the potatoes that she's preparing for dinner. These alterations to Jeanne's existence prepare for the climax on the third day, when she unexpectedly has an orgasm with the day's client, after which she stabs him fatally with a pair of scissors.

53.) Jean de Florette/Manon of the Springs directed by Claude Berri (1986). A period drama film, based on a novel by Marcel Pagnol. It is followed by Manon of the Springs (Manon des Sources). The film takes place in rural Provence, where two local farmers scheme to trick a newcomer out of his newly inherited property. The film starred three of France's most prominent actors – Gerard Depardieu, Daniel Auteuil, who won a BAFTA award for his performance, and Yves Montand in one of the last roles before his death. At the time the most expensive French film ever made, it was a great commercial and critical success, both domestically and internationally, and was nominated for eight Cesar awards, and ten BAFTAS. In the long term the films did much to promote the region of Provence as a tourist destination.

54.) Good Job (Beau Travail) directed by Claire Denis (1999). Loosely based on Herman Mellville’s 1888 novella Billy Budd. The movie is set in Djibouti, where the protagonists are soldiers in the French Foreign Legion. The film examines conflicts between the men, and examines the complex and sometimes problematic effects of all-male homosocial military environments.

55.) Goodbye to Language (Adieu au Langage) In 3-D! directed by Jean-Luc Godard (2014). ) Godard's 42nd feature film and 121st film or video project. Godard's own dog Roxy Miéville has a prominent role in the film and won a prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Like many of Godard's films it includes numerous quotes and references to previous artistic, philosophical and scientific works, most prominently those of Jacques Ellul, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Mary Shelley.

This list of films is, of course, incomplete, but it's a good start! Check out these great French films! many of them are streaming on Hulu as part of their amazing Criterion Collection.