I'm currently editing and laying out a new zine entitled "Our Eyes, Spinning Like Propellers: Cinema and Community" by Steve Elkins. Here is an excerpt on Jean-Luc Godard:

Most people know Godard for a handful of revolutionary films made in the early '60s associated with the French New Wave which changed cinema forever; however, his most important work has arguably been done since then. For the last seven decades, Godard has effectively embarked on an anthropology of the entirety of Western civilization: few filmmakers have probed deeper into who we are, and why. These films are as important to sociology as they are to avant-garde art, to pop culture as they are to philosophy, and very few people are aware of these monumental works, even fewer are discussing them.

"A Woman Is A Woman" (1961): After changing movies forever with his debut "Breathless," then receiving threats of expulsion and death from the French government for making a film that exposed their official policy of torture in Algeria ("Le Petit Soldat"), Godard made this radical musical comedy, an explosion of cinematic creativity that even today feels ahead of its time. It was "a reaction against anything that wasn't done," Godard said, "It went along with my desire to show that nothing was off-limits. An Inquisition-like regime ruled over French cinema. There were taboos and laws and I wanted to show that it all meant nothing. French cinema is dying under the weight of false myths. The myths had to be destroyed for French cinema to be reborn."

"Vivre Sa Vie" (My Life To Live, 1962): An argument with philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre that doubled as a love letter to Godard’s wife Anna Karina. A hallmark of Sartre's philosophy was the idea that a person is defined by his actions, his outward reality, and that belief in an essence distinct from public and social phenomena was unfounded. Since the early 1950s, Godard had been arguing that Sartre's opposition of outer existence and inner essence was fallacious because it was transcended and resolved in the cinema, which shows how the collision of light with the surface of the world reveals inner and metaphysical qualities. "My Life To Live" examines the relationship between surface and meaning by following "a pretty Paris shopgirl (Godard's wife, Karina) who sells her body but keeps her soul." "I want to prove that existentialism presupposes essence, and vice versa," said Godard, "and that this in itself is something quite beautiful."

"Pierrot Le Fou" (1965): Jean-Luc Godard on his film Pierrot Le Fou: "You say 'let's talk about Pierrot.' I say, 'What is there to say about it?' ...If you wake the woman you love in the night, you don't telephone your friends to tell them about it afterwards. Difficult, you see, to talk about cinema...because life is its subject, with scope and colour as its attributes...life itself which I wanted to make so much of so that it would be wondered at...the only great problem with cinema seems to me more and more with each film when and why to start a shot and when and why to end it. Life, in other words, fills the screen as a tap fills a bath, which is simultaneously emptying at the same rate at the same time. It passes, and the memory which it leaves us is in its own image...this double movement, which projects us towards others while taking us inside ourselves, physically defines the cinema...Celine, let's leave him to literature...suffering and piling book upon book amid the regiments of language, we, with the cinema, are something else, life first of all, which isn't new, but difficult to speak of, one can barely live it and die, but speak of it, well, there are books, but in the cinema, we have no books, we have only music and painting, and even those, as you know, can be lived but rarely spoken."

"Masculin Féminin" (1966): A film about youth and sex in France in 1965, on the eve of legalizing contraceptives for women which had been banned since 1920. The first direct vote for a French head of state since 1848 was about to be determined by the youth of France who wanted "the pill," prompting Godard to make this sociological study of the new generation he called "the children of Marx and Coca-Cola." "The class struggle is no longer the same as we were taught in books," Godard observed, "it's true that Bob Dylan is a link between the yé-yé kids and politics, a way to bring the two together. But, you know, I think it was Baudelaire who said that it was on the toilet walls that you see the human soul: you see graffiti there - politics and sex. Well, that's what my film is."

"Alphaville" (1965): A cockeyed fusion of science fiction, surrealist poetry, and pulp detective noir starring a computer obsessed with Jorge Luis Borges, "Alphaville" (originally titled "Tarzan vs. IBM") emerged from Jean-Luc Godard's conversations with cybernetics and artificial intelligence researchers in the early 60s to understand "to what extent electronic brains and the calculation of probabilities are becoming important in the lives of businessmen and heads of state" to create a society in which "people should not ask 'why', but only say 'because'." "Alphaville" is also perhaps the only science-fiction film ever made without a single set or special effect. Instead, Godard developed his own guerilla filmmaking methods on the streets of Paris (causing his cinematographer to exclaim: "He'd like to swallow the film and process it out his ass") to place an X-ray on contemporary life, art, political theory, and love, to expose "the future" as a veiled inner reality of the present.

"La Chinoise" (1967): Documents a semi-fictional Maoist cell at Nanterre University working through their first steps toward "changing reality." The film is widely understood as prophetic: less than a year after it's release, almost a million people marched in Paris to denounce the French government, occupied the universities and police stations, set fire to the Paris stock market, while strikes spread all over France, factories were taken over by their workers, theaters were turned into public forums where people from all walks of life could finally speak, and the flow of gasoline to the capital was stopped, causing Godard to remember Paris that month as "a moment where one heard the sound of pedestrians in the street simply because there was no more gasoline.”

"Weekend" (1967): In the final years of the ‘60s, Jean-Luc Godard made a string of explosive films that attempted to encapsulate the global revolutions taking place in a new language adequate to them. “Weekend” shows the Apocalypse of Western civilization as an endless traffic jam of crashed cars and planes (filmed as if it were modern sculpture), “Sympathy For The Devil” contrasts the incommensurable realities of The Rolling Stones and the Black Panthers, and “Le Gai Savoir” attempts to entirely deconstruct human language and the blitzkrieg of media signals we’re bombarded with, to rebuild them on stronger foundations.

"2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her" (1967): In the mid-1960s, Charles de Gaulle began restructuring French society to become modeled on American consumer culture. One of the costs of this development was that some middle class housewives in Paris had to become prostitutes to afford the newfound "necessities" of living. In outraged reaction, Jean-Luc Godard made "2 Or 3 Things I Know About Her," an anthropology of the Americanization of Paris, which considers the transition to "modern living" as a gradual collective prostitution of the mind. In this remarkably beautiful and dense film, Godard places a microscope on the structure of our daily lives, colliding the veiled inner meanings of words and objects with dazzling speed, resulting in mind-bending insights into the invisible borders that define us, from the macro (“Where does the individual end and society begin?”) to the micro (“Where does the material end and the spirit begin?”). Features the classic scene where a swirling cup of espresso becomes the formation of consciousness and the universe.

"Le Gai Savoir" (1968): "It was not going to be possible to make the new cinema by using the language of the old," wrote James Monaco about "Le Gai Savoir" in 1975. "Having returned to zero, Godard had to start over again. LE GAI SAVOIR is the first step. It is Godard’s ultimate effort at 'semioclasm,'(1) the name critic Roland Barthes gave to the necessary job of breaking down the signs of the languages we take for granted in order to rebuild them on stronger foundations. Its aim is nothing less than the beginning of a rigorous examination of the systems of signs through which and by means of which politics, love, beauty, and existence are expressed and understood. 'What is really at stake,' Patricia discovers, 'is one’s image of oneself.'

Cinétracts (1968): Godard breaks into the Centre du Cinema and steals their cameras to distribute them amongst rioters on the streets of Paris during the cataclysmic upheavals of May '68. He and Chris Marker (in collaboration with Alain Resnais and other luminaries of French cinema) create a new form of DIY cinema called Cinétracts, which were edited in-camera on single rolls of cheap 16mm film no longer than 2 to 4 minutes each, and released to the public anonymously. Anticipating the effects of the digital revolution by several decades, this allowed Godard to work entirely outside of the studio filmmaking system and chains of theatrical distribution, eliminate hierarchies and power imbalances from the filmmaking process (theoretically), and deal with events on the streets as they were happening. They often contained still photographs with hand-scrawled words added.

"Numéro Deux" (1975): In the early 1970s, Godard turned from both traditional theatrical distribution and the supremacy of large-format film by making DIY films shot mostly on portable 16mm and video. By 1975 and Numéro Deux, Godard was already using video as an aesthetic and philosophical tool to be pondered, tested and abused, anticipating the digital revolution by several decades, and allowing him to work as a guerilla filmmaker completely outside French film industry. It also placed all means of production, distribution, and exhibition within his own hands. In one of his most radical works from this period, "Numéro Deux," the entire movie takes place on two television screens within the film frame. Godard procured funding for the film by saying it would be a remake of his first film "Breathless", which he never actually intended to do. "Numéro Deux" is an examination of sexual economy within the family and the relationship between media (films, factories, print, video) and the human body.

"Ici Et Ailleurs" (1976): Initially intended to be a documentary about the Palestinian armed struggle (shot in Lebanon, Jordan, and the West Bank between 1970 and 1974), Godard transformed his footage into a breathtaking meditation on how each of us develops our sense of truth, history, and our political worldview. A searing analysis of how our perceptions of ourselves and others are sculpted from our relationship to images and texts, those slippery slopes upon which our understanding of history (and other fictions) is recorded and handed down to us, the film has perhaps never been more relevant than now, in the age of Facebook and the internet.

"King Lear" (1987): Godard's 1987 avant-garde "adaptation" of Shakespeare starring Woody Allen, Molly Ringwald, and Norman Mailer! A late descendant of Shakespeare attempts to restore his plays in a world rebuilding itself after the Chernobyl catastrophe. Godard himself plays Professor Pluggy, an eccentric with video cables for hair who is obsessed with Xeroxing his own hand.

"Helas Pour Moi" (1993): Jean-Luc Godard's rumination on the meaning of all creation, from God to Bruce Willis movies, set to the music of Arvo Pärt and Keith Jarrett. The film explores the transmission of the sacred across time, through a surrealistic, modern take on the Greek myth of Amphitryon, where Zeus (played here by Gerard Depardieu!) descends to earth to seduce a woman by disguising himself as her husband. A gorgeous meditation on the idea of Incarnation, the penetration of the divine in love, art, language, and history, described by Godard as his attempt to "see the invisible...the other half of the universe beyond images and beyond stories."

"Je Vous Salue, Sarajevo" (1993): Culture is the rule, and art is the exception. Eveybody speaks the rule: cigarette, computer, T-shirt, TV, tourism, war. Nobody speaks the exception. It isn't spoken, it's written: Flaubert, Dostoyevski. It's composed: Gershwin, Mozart. It's painted: Cézanne, Vermeer. It's filmed: Antonioni, Vigo. Or it's lived, and then it's the art of living Srebrenica, Mostar, Sarajevo. The rule is to want the death of the exception.

"Histoire(s) du Cinema" (1988 - 1998): Though few have seen it, the ones who have tend to consider this to be Godard's magnum opus, arguably one of the most important contributions to the humanities (in any medium) of the 20th century. Facing the deceptively simple question "What was cinema?", Godard develops a highly theological and realistically mystical philosophy of history, spun in the densely textured poetic style of "Finnegan's Wake" and the Cantos of Ezra Pound, which seeks to demonstrate how our personal relationship to projections of flickering light creates (rather than reflects) the world we live in, directly impacting the social and political realities of people in far away places we never see. Nearly five hours long, with 200 hours of footnotes planned for it's encyclopedic knowledge of seemingly everything.

"The Old Place" (1998): Today, you don't see the image, you see what the title says about it. It's modern advertising. This image that you are, that I am, which Walter Benjamin speaks of, of that point where the past resonates with the present for a split second to form a constellation. "The work of art," he says, "is the sole apparition of something distant, however close it may be." The origin is both what is discovered as absolutely new and what recognizes itself as having existed forever. Between the infinitely small and the infinitely large we'll eventually find an average. And the average will be the average person, no doubt. Artistic thinking begins with the invention of a possible world, then using experience and work, painting, writing, filming, to confront it with the outside world. This endless dialogue between imagination and work allows for the formation of an ever-clearer representation of what we agree to call reality. 19 people attended the Crucifixion, 1,400 the first performance of "Hamlet" and two and a half billion attended the World Cup final. In the immensity of the universe, can time be recounted? Time as it is, as such and in itself? Art wasn't protected from time. It was what protected time. We work in the dark, we do what we can, we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. Maybe we're the ghosts of people taken away when everybody vanished.

"De L'Origine Du XXIe Siècle" (2000): The spirit borrows from matter the perceptions it draws its nourishment from, and gives them back as movement stamped with its freedom. Nothing conflicts with the image of the beloved more than that of the state. The state's rationale directly opposes the sovereign value of love. The state in no way possesses, or else it has lost, the power to embrace, before our eyes, the totality of the world, that totality of the universe offered externally via the loved one as object, and internally via the lover as subject.

"In Praise Of Love" (2001): "The measure of love is to love without measure."

-St. Augustine

"Liberté et Patrie" (2002): Trying to see something. Trying to picture something. In the first case, you say, "Look right there." And in the second, "Close your eyes." What's the best way of knowing if someone is trustworthy? You ask him, "What have you read?" If he answers, Homer, Shakespeare, Balzac, then he is not trustworthy. But if he answers, "Depends what you mean by reading", then there's hope. The eyes are freedom, the hands are fatherland. What does the wind do when it's not blowing? The sun is an example of the supremely sensitive being, because it can always disappear. O universal time when nothing was mute for the eyes of a child.

"Notre Musique" (2004): One of my top three favorite films of all time, a triptych that sets Dante's three Kingdoms of the afterlife in the modern world, in which Heaven is a beach guarded by US Marines and Purgatory is a (real) congregation of the world's great poets in the ruins of the Sarajevo library, where two million books (and people) had just been destroyed in a bombing. As they begin one of the most moving discussions ever captured on film about the complexities of forgiveness, we follow the parallel stories of two Israeli women propelled by these reflections in opposite directions: one toward martyrdom and the other toward perceiving the face of her "enemies" as the outline of the Absolute, the geography of the Infinite which traces "where God passes." Inspired by the thought of Martin Buber, Hannah Arendt, José Lezama Lima, and Emmanuel Lévinas, "Notre Musique" is a profound work of theology that considers whether heaven and hell are in fact the same place: both "protected" by a divide across which we cannot embrace "the Other," who is our mirror. Featuring Arab poet Mahmoud Darwish.

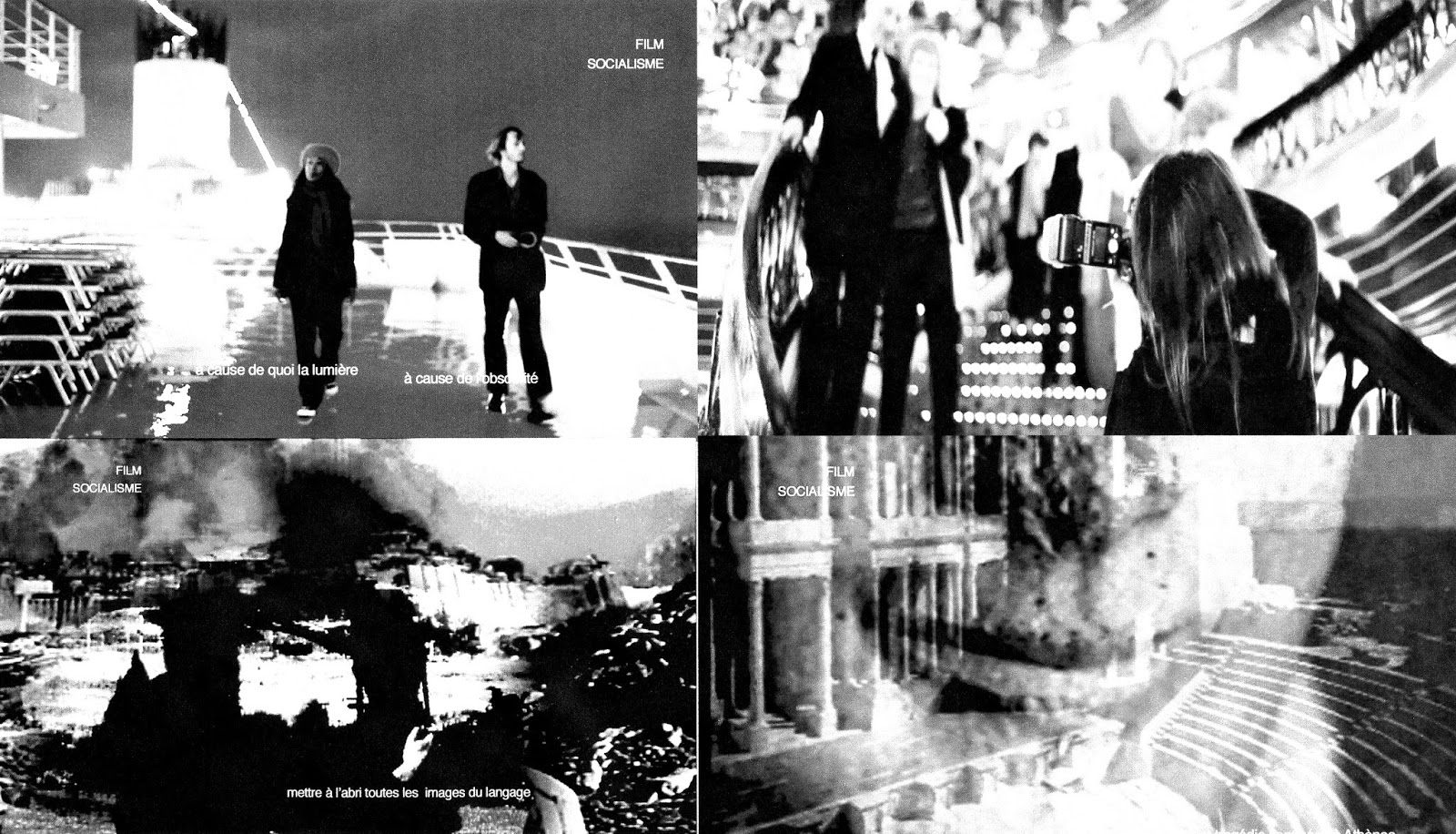

"Film Socialisme" (2010): We concluded Hibbleton Gallery's two-month Jean-Luc Godard Retrospective with a discussion of his current activities building his own homemade 3D movie camera at the age of 85 which he used to shoot his first 3D feature "Goodbye To Language," prior to a screening of "Film Socialisme" (2010), Godard's first work shot entirely on digital and cell phones, in which modern day tourists (including Patti Smith!) take a cruise ship through the sites of "our humanities" (Egypt, Palestine, Odessa, Greece, Naples, and Barcelona). Said to have anticipated the Greek debt crisis and the Arab spring, an encyclopedic illumination of the complex mythologies under which we all live, from the origins of modern civilization to cell phones, from Old Testament Israel to Youtube cat videos, from aerobics to globalization, from the conflict between universalist ideals and national origins to the tension between humanism and the enduring particularisms of ethnicity and historical memory.

The zine will be released on Friday, June 6th at BOOKMACHINE books + zines, during the Downtown Fullerton Art Walk. There will also be an accompanying art + video installation. See you then!

Love,

BOOKMACHINE books + zines

The Magoski Arts Colony

The Downtown Fullerton Art Walk