The following is from a work-in-progress called "The Bible: a Book Report" in which I read each book of the Bible, summarize it in my own words, and occasionally give some commentary. I will also include biblical artwork by famous artists.

I must admit, I had a rough time with the book of 2 Chronicles, mainly for two reasons: 1.) It’s really long, which I wouldn’t necessarily mind except for the fact that 2.) It’s basically a re-telling of the stories of 1 and 2 Kings. It’s like you’re reading a novel…Chapter 2 is action-packed, Chapter 3 is full of intrigue, but then in Chapter 4 the author repeats the events of Chapter 2. WTF? It really messes with the flow of the story.

And so I found myself reading not just the text of 2 Chronicles, but also some commentaries, in an attempt to figure out why the Bible would be so obviously repetitive. But reading commentaries is a deep well, and it’s easy to get stuck there. As with anything that people have been studying for a long time, there are many conflicting views. For example, in my book report on 1 Chronicles, I took the view that both books of Chronicles were written in the 6th century B.C.E., from the perspective of the Jews in exile in Babylon. Well, today I read another view that these books were written in the 4th century B.C.E., from the perspective of Jews who had been allowed to return to Israel, under Persian rule. Which is it? Today, I tend to think it was the 4th century. I’m really not sure though.

|

| I have been using the Cambridge Annonated Study Bible, which is (kind of) helpful in clearing up some confusing parts. |

Why does this matter? Who cares if the text was written in the 6th century B.C.E. or the 4th century B.C.E.? Well, it matters if you want to know the proper context of what was happening historically when the book was written. As a professor of English with a Masters degree in literature, I was taught, and try to teach the vital importance of context when trying to understand a text, sacred or not.

So where does that leave me, with this book report project? Confused and overwhelmed, to be honest. For now, I guess, I’ll continue as I was before, with my summaries of the books. However, when I feel it is important to bring up questions of context, as I am doing here, I will not hesitate to do so, with the understanding that such questions are thorny and hotly debated.

In presenting my report in 2 Chronicles, I will take the view that it was written in the 4th century B.C.E., after the Jews had returned form exile in Babylon, and were in the process of re-establishing themselves as a religious and cultural community. Whether you believe the book was written in the 6th or 4th century B.C.E., the fact remains that the authors are describing events that happened centuries prior to the writing (like King Solomon’s monarchy), and this is problematic from a historian’s perspective. Thankfully, the Bible (in my view) is not primarily a book of history. It is, I believe, primarily a book of religious devotion that occasionally intersects with history.

Before I get to the summary part, I’d like to share another insight I had about why 2 Chronicles is so repetitive, as I was taking a walk. An important motif in the Bible (both Old and New Testament) is repeating the same story from different perspectives. We see this clearly in the four gospels about Jesus (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John). Why are there four gospels, and not one? Why do they repeat many of the same stories in different ways? Why does the book of Deuteronomy repeat the stories of Exodus and Numbers? Why does Chronicles repeat the stories of Kings? I think it has to do with audience and context. The Bible was written to many different audiences living in different times and places. I think the repeating of the stories speaks to this idea that it is not just the text itself, but the audience, who help create meaning. It’s a two-way street, so to speak. That, I think, is why a book like 2 Chronicles repeats familiar stories in a new way. The stories are being told to a new audience under new circumstances. My mom is fond of quoting the verse that the Bible is “living and active.” I never quite knew what that meant until today. I think it means that the neither the text, nor the stories it relates, are static. Instead, when we read them, we participate in the meaning-making process. Even the Bible writers seemed to understand this.

|

| The Four Gospel Writers (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John) |

Okay, now to the text of 2 Chronicles. Because this book is a re-telling of stories already told in Kings, I have decided to focus on the elements of the story that are either omitted or changed in the Chronicles account. I am doing this with the help of my handy dandy Cambridge Annotated Study Bible. It would be very helpful if someone were to line up the two accounts side-by-side, so the differences were more apparent. I’m sure some scholar has done that at some point. Anyway, here goes…

2 Chronicles begins with the ascension of King Solomon to the throne of Israel. Unlike in the Kings account, in which this is described as a family struggle for the throne between Solomon and his brother Adonijah, 2 Chronicles describes a peaceful and seamless transfer of power.

The account in 2 Chronicles of Solomon’s dedication of the temple in Jerusalem is twice as long as the account in Kings. Interestingly, the Temple is built on Mount Moriah (in Jerusalem), which is the same site where God called Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac way back in Genesis. The implication, I think, is that this site is a place of great devotion and faith in God. The extensive focus on the Temple, and the rites of worship reflect the 4th century B.C.E. preoccupation with re-establishing temple worship, after the return from exile. During the dedication, specific names of priestly families are given. Also, when the temple is being dedicated, a song is sung, whose theme is: “For He (God) is good, for his steadfast love endures forever.” God is not described as jealous or full of vengeance. Rather, He is a God of love. Ironically, Israel’s painful experience of exile had transformed and softened their view of God, to an extent.

During King Solomon’s prayer of dedication of the Temple, God is also presented as a God of forgiveness. Prayer in the Temple will bring restoration, even to a defeated people like Israel. Solomon prays, “When your people Israel, having sinned against you, are defeated before an enemy but turn again to you, confess your name, pray and plead with you in this house, may you hear from heaven, and forgive the sin of your people Israel and bring them again to the land that you gave to them and to their ancestors.” God is described, not as distant or unknowable, but very near, and relatable. Indeed, God is meant to somehow “dwell” within the Temple in Jerusalem. “Only you (God) know the human heart,” Solomon prays. When Solomon finishes his prayer of dedication, “the glory of the Lord filled the temple,” and all the people pray, “For he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever.”

God appears to Solomon and again presents a softer view of himself, as a God of healing. When Israel is suffering, if they humble themselves and pray, God will “heal their land.” However, if Israel is disobedient, God will not hesitate to scatter his people again. So, the picture of God is sort of like a fatherly figure: both disciplining, and also loving his son Israel.

|

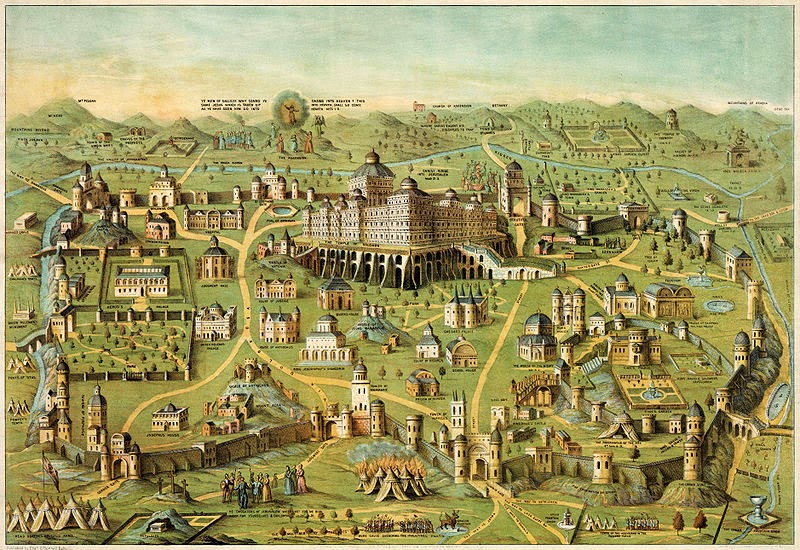

| "The Ancient City of Jerusalem with Solomon's Temple" by Charles O'Donnell (1871) -- not to scale |

An important omission from 2 Chronicles is the part in Kings where Solomon marries 700 wives, has 300 concubines, begins to worship foreign gods, and basically curses his family dynasty. The picture of Solomon in Chronicles is pretty much flawless, as opposed to the more complex picture in Kings. Perhaps the writers couldn’t stomach the fact that the same guy who built and dedicated the Temple, could also be a fallible human being.

The writers of Chronicles clearly side with the kings of Judah, who (sometimes) keep the commandments of the Lord, as opposed to the northern kings of Israel, who worship false gods. This is shown in a battle between Judah and Israel, when the Judean king Abijah defeats the much larger northern army of Jeroboam. Abijah shouts to them, “we have kept the charge of the Lord, but you have abandoned them.”

However, not all is well, even in the more faithful land of Judah. King Asa, who is generally well-regarded for expelling most idol-worship from Israel, makes a fatal error by entering into an alliance with Aram, instead of relying on God. As punishment, Asa gets diseased feet.

Perhaps the most important omissions from 2 Chronicles are the roles of the prophets Elijah and Elisha, who are so central to the stories in the books of Kings. Omitted is the demonstration at Mount Carmel of the fire from heaven. The only mention of Elijah is a letter he sends to the Judean king Jehoram, warning him of a coming plague. That’s it. The reason for this glaring omission, I think, is that the spiritual heroes of Chronicles are not so much the prophets, but rather the good kings (like Solomon) and the Levitical priests, who were especially important in re-instituting temple worship at the time of the writing of these books.

One interesting element included in both Kings and Chronicles is role of female leaders. For a brief period, Judah has a queen, instead of a king. Her name is Athalia. Unfortunately, she is evil and is killed by her own people. Then, under the reign of King Hezekiah, there is a female prophet named Huldah, and she is well-respected. The king heeds her advice.

|

| "Huldah Prophet of Jerusalem" by Dina Cormick (1989) |

2 Chronicles continues the same pattern presented in 1 and 2 Kings. The Kings who follow God’s laws and do not allow any foreign gods to be worshipped enjoy success and prosperity. The kings who allow the worship of other gods get defeated by foreign nations, and often die in unpleasant ways. Many kings are a mixed bag, some are outright evil, and some are heroic reformers, like Hezekiah and Josiah. The outcome of history is thus contingent upon the people's obedience to their God. This is, needless to say, an enormous burden of responsibility.

Near the end of 2 Chronicles, Judah is defeated by Babylon (under King Nebuchadnezzar) and taken away into captivity, just as is described in 2 Kings. However, there is a powerful explanation given as to why this happens in Chronicles: “The Lord, the God of their ancestors sent persistently to them by his messengers, because he had compassion on his people and on his dwelling place; but they kept mocking the messengers of God, despising his words, and scoffing at his prophets, until the wrath of the Lord against his people became so great that there was no remedy.” Soon, in our journey through the Bible, we will come to a series of books written by prophets during the reign of these various kings of Israel and Judah. The prophets often lead lonely, persecuted lives.

|

| "The Destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar" by William Brassey Hole |

One of the main reasons I think 2 Chronicles was written after the return from Babylon in the 4th century B.C.E. is because the book itself describes the return from captivity, under the reign of the Persian emperor Cyrus. This event is spoken of in the past tense, strongly suggesting a post-exile date for the book. Some people, however, consider the part about Cyrus to be a later addition, and argue for a 6th century B.C.E. date. These are the kinds of things Bible scholars argue about.

Finished! Phew. That was a tough one. Stay tuned for the book of Ezra, which is much shorter, and new things happen…