“All the yesterdays, no matter how good they were, how bad, they are plowed under; there is nothing we can do about it. They are gone and forgotten. Tomorrow is the great hope. But today we have in our hands, squeeze it like an orange, get all the juice out, enjoy it, savor it--each day as we go. That is all we have.”

--Florence Millner Arnold

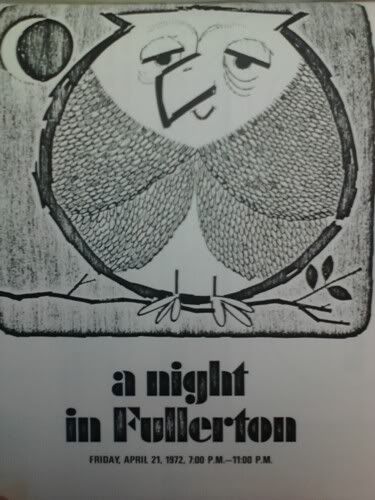

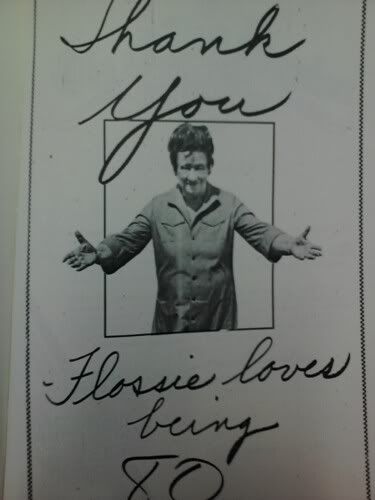

Florence Millner Arnold (aka "Flossie") was a local hero of Fullerton culture. She was a music teacher for much of her career. In the 1950s, she started painting and became actively involved in the arts, a passion that would consume the rest of her life. Her list of cultural contributions to the city of Fullerton is staggering: She became president of the Orange County Art Association, was a member of the American-European Cultural Exchange, co-founder and chairman of the annual “Night in Fullerton” (which she started in 1966), a member of the City of Fullerton Cultural and Fine Arts Commission, chairman of Bicentenniel Committee for Art in Public Places for the city of Fullerton, president of the Muckenthaler Cultural Center Annual “Florence Arnold Children’s Art Scholarships Exhibition,” and president of the CSUF Art Alliance. Needless to say, she received numerous awards and accolades, including, on her 85th birthday the city of Fullerton presented her with the “Key to Our Hearts.”

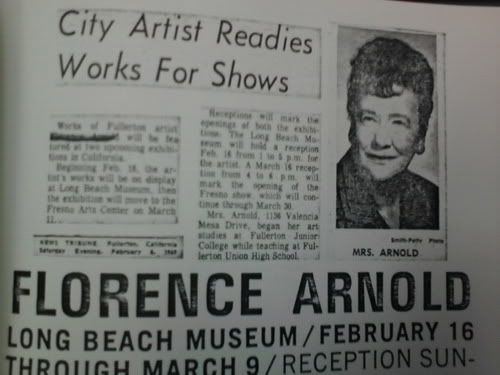

She also became a celebrated artist in her own right, whose work was featured in the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, Art Week Magazine, and in the Archives of American Art in the Smithsonian Institute.

From 1985-1987, a student at Cal State Fullerton interviewed her several times for the CSUF Oral History Project. These interviews were transcribed and published in an 85-page volume, which is available at the CSUF Center for Oral and Public History. I have spent the past few days reading the story of this extraordinary woman’s life. I wish I knew her, but after reading this, I feel like I kind of do.

Flossie was born in Reno, Nevada in 1900 to a miner and a farm girl from Missouri, both of whom had a profound impact on her life. She recalls, “Mother always had a project she was fighting for. First, it was votes for women. Then she wanted playgrounds for the schools. She organized the first PTA in Reno so that they could have swings and slides on the playground. Then mother became a militant suffragette in 1914, 1915, and 1916. All the great women that were promoting the cause came through and stopped in Reno...Ann Martin and the other great women who stopped there, would come to the house and have dinner and we would talk. Then out into the street we would go. I remember carrying my little flag that said “Votes for Women” on it...The women would stand and try to gather a crowd, and the men would heckle them.”

Her father, George, was a miner by profession, but a poet at heart. Flossie recalls, “He was a poet. All of the letters he ever wrote to me as a little girl were written in poetry. I can remember, growing up, he would read to us every evening, Dickens, the classics, and all the stories that he thought we ought to know...so I was well-versed in lots of literature just from father reading to us.”

Recalling her parents, she said, “I think that those two people, those two strong human beings were certainly influential in my life, this father who was a poet, a dreamer with literature and music very much a part of him; and mother who played the very down to earth realist who held things together.”

As a young woman, she took a vacation to Mendocino (near San Francisco) to visit a friend. Here she met the boy who would become her husband, Archie: “When we were going down to Mendocino, we passed a lumber mill. There were two fellows out at the end of a boom stick where the scraps were kept, and they were waving their little sailor hats at us. Dorothy said, ‘Those are two punks from Anaheim, and it’s the only thing we have to entertain us this summer. There’s no one else in this town of Mendocino.’ So that night when we went to the movies in the back of the drug store (where each night they would show a movie) sure enough, there were the two boys, Waldo and Archie, in back of us. They kept, of course, making all the noises that boys do and, I think, Archie hit me once. He tried to see how near he could get without hitting me, but, nevertheless, those two pesky boys were there.”

Florence took a job teaching music in Sacramento: “I didn’t know anything about teaching. My experience in teaching had been six weeks in a second grade and a semester of harmony in the Oakland high school. And I was really ignorant, making it up minute by minute. Every twenty minutes, they would send in another class...I didn’t know if it was going to be a second grade, or a fourth grade, or a first grade. I would open those music books, and we just winged it. I don’t know to this day how I did it. When I think back on it, it was a miracle.”

Flossie and Archie got married and moved to Fullerton, near where Archie’s family was from. Flossie began teaching music in Placentia in the 1920s, a fascinating time in the history of Orange County, a time when there was an active Ku Klux Klan. She recalls: “You couldn’t get a job in Fullerton if you were a Catholic.” Also, at that time, schools were segregated into “white” schools and “Mexican” schools. “We had three Mexican schools in Placentia,” she remembers.

As a teacher, Flossie was an innovator, often doing things different from standard practice. When she went to teach in Placentia, she remembers, “They had a superintendent who was just pathetic. He was afraid of everything, and all he knew was to make people march and to keep a tight hold on everything. He thought the place would go to pieces if he let go with his strict regimen that he had.”

By contrast, Flossie made it her mission “to show other people how good they were, how great they were. I would take the youngsters and show them that they could do it. This became my ambition or my fun in life...sometimes, children don’t have an opportunity to show how great they are. They are circumscribed with rules and regulations, and somebody is there with a whistle over them or with a time clock...I think so many teachers miss the point. They think the subject matter is the important thing or the answer, rather than turning it around and saying, ‘Let’s take the child first.’”

In treating her students with sincere interest and respect, she taught them to do the same: “They recognized that, well, she is almost human and, maybe, she is a friend...Many teachers get bored too fast. They don’t know the fun of creating. And living is creating.”

Flossie and Archie had a daughter, Adrienne, in 1932. Because of her teaching job, Flossie decided to seek a “nanny” of sorts to look after he daughter. She was referred by a friend to Ida Irwin, an African American woman (one of very few living in Fullerton both then and now) who lived in Truslow, on the “other side of the tracks,” one of the few places where minorities could get housing in Fullerton in those days, because of racist housing covenants. The story of Flossie and Ida’s relationship is very beautiful and is worth quoting at some length:

“I never had been around a black person in my life. The only black person I had ever seen was the porter on a pullman train. We saw them frequently traveling from San Francisco to Reno, but I had never been around a black person. In Reno there weren’t any. There were Italians but no black people. I had never touched a black person. I had never been that near to them. But I was desperate, of course, wanting to find someone to come and live in the house with me.

So I went to meet Ida Irwin. I went down to East Truslow one night and went to the door and knocked. This bevy of black children, all five of them, answered the door. I said, ‘Could I speak to your aunt?’ It was a very touchy situation because I was not sure of my base at all. I was just petrified, really, because I didn’t know who these people were. I was so afraid that I would do something wrong, that I would be at fault. I didn’t know the protocol, how you approach these people. But, anyway, I talked to Ida Irwin and asked her if she would like to come and live with me for awhile or stay while I was teaching and be there at night when Adrienne came home. So with all those little black faces around, Ida said, “Well, we will try it.” I really believed that she wouldn’t even speak to me. I was the one in trial, not Ida.

So she came to live with us. One of the greatest experiences of my life was to know that great woman. She was a marvelous person. She was a Christian Scientist which I thought was very interesting. She read her Bible, her Science and Health every day. She was so regal and so beautiful, and I kept walking around her. Of course, I was just afraid that I would say something wrong or do the wrong thing. So one day just a few days after she had been there and we were in the kitchen, I said, ‘Ida, can I put my arms around you and touch you and hold you?’ And she said, ‘Yes.’ And I hugged her and I kissed her, and I hugged this great beautiful woman. I can’t tell you how beautiful she was. She was just an elegant human being and to have her accept me was just one of the most elegant things that has ever happened in my life. She was willing to come into my home and take care of that little girl and see that she was cared for when I wasn’t home. Ida was my joy and my life.

Ida and I, of course, would discuss the affairs of the world, and this was long before the march in Georgia and Dr. King. We knew the war was coming. You knew it. Everybody could feel it. And I used to say to Ida, ‘Now remember, Ida. I’m with you. You are going to take care of me when this holocaust comes.’ And she would say, ‘Yes, I’ll take care of you.’ I was the one that needed help...I lived through that period. I experienced what many people read about. We knew about black people and other people, but to have that experience in my home was very interesting. I could bridge that gap in civilization, you might say, in my lifetime.”

When asked about her religion, Flossie explained: “I’m free to go into any church and feel comfortable. I could go into a Catholic church because I used to sing in the Catholic Masses when they needed a soprano to sing the requiems. I feel good in churches. Churches are a wonderful place to be; I like the ambience of a church. I like the idea that people gather there for good. I like to spell God with two o’s, put another o in there. Everything that is good is worth pursuing. I’m helped, I’m strengthened; it’s the other part of life that you hold onto. You need it, just to know that the Lord’s Prayer is there, and that many people recite it in many different ways and in many different places. I’m pleased about that. I can go into any church and feel comfortable and feel good because I know they are reflecting that good. They want the best, and they want the best for everyone. I like that philosophy. It’s upbeat, and joyous, and fun. I’m glad I can go into any church and feel comfortable because they’re all reaching for the optimum. They want the best for everyone. Of course, there are so many paths to getting there, getting at the truth. The truth is the truth wherever you find it, that little kernel of truth. It’s wherever you find it; it’s a blessing and it’s there. The search for that truth is a marvelous thing. It’s been my mainstay; it’s been my support through my life. When I’m in trouble, I know how to say [the hymn] ‘Shepherds show me how to go...’ and say The Lord’s Prayer if you’re in trouble and need help. Say it! It will give you sustenance. I haven’t professed any one religion; I feel comfortable in any church.”

In 1950, an unlikely experience pushed Flossie’s life in a new direction. She recalls: “Adrienne was in high school and I was taking her down to summer school at Fullerton High School. As I was walking down the hall, Arla Smith, an art teacher, saw me and grabbed me by the arm. She said, ‘Come in and sit down. I need twenty people to keep this class going this summer. Of course, I don’t have enough people, so just sit there.’ Being an accommodating person, I sat down; and she gave me a brush or a pencil and some paper. Everybody was doing watercolors. People were sketching, and they would sit on the lawn and sketch those arches, the houses and the trees. It was amazing to me. There were teenagers in the class and middle-aged people. I was fifty years old.”

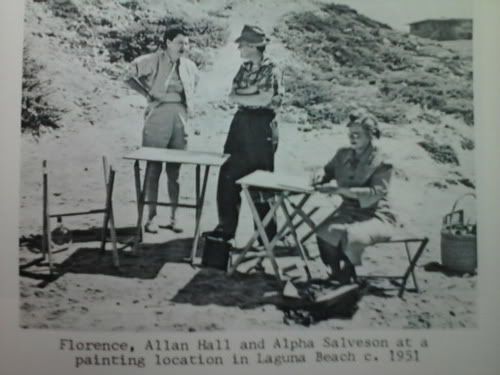

Florence quickly discovered a passion for painting, and joined together with a group of other local artists, and started taking “art trips”: “We would meet on Saturdays, pool our cars, and go all over this county. We would go down to Laguna, to the brick yards out in Orange, any industrial site that we could find, and out to Hunt’s. We just went every place to sketch and to do those watercolors.”

After a career of teaching music, a generally social activity, painting allowed Flossie to tap into her more solitary self: “Being a gregarious person, I like to be where there are people. People, I think, are my thing. If I have a forte, it is people. I really enjoy people more than anything in the world. I like to be in crowds. I like to be in the classroom. I like to be where there is action and people doing things. That is one thing I enjoy more than anything. But painting is a lonesome thing. It is a oneness. You are all by yourself. You see, when you are teaching music, you are in front of everybody, and you are making it work. Painting is off in a corner by yourself. There is just no one there. You have to feel that oneness, and you have to get that oneness together. That was a strange thing for me to do because, all my life, I had been the action one, in front of an audience or in front of a roomful of children. Crowds are what stimulate me. But here, I would be off in a little corner all by myself, hour after hour, painting. It took me a little while to understand that was what I was going to do.”

Early on in her career, she was given a valuable piece of advice from an art teacher. She asked him, “Do I have any talent?” He replied, “I wouldn’t know talent if I met it in the middle of the street. But you have persistence.”

Flossie took to painting with the same gusto and passion that she had taken to music and to teaching. To her, music and art and teaching were all connected: “My painting is a direct outgrowth of all the things I’ve ever done. Everything is grist to your mill. It’s a continuation of living...painting is marvelous, and music is marvelous. There is no end to the enjoyment that I have in both. I couldn’t live without music. I don’t want to. I don’t plan to. I don’t want to live without color. I don’t want to live without art. But, mostly, I don’t want to live without people. People are the most elegant things in this world, the give and the take and the fun of communicating, comes from people. And art is a means of communicating, the same as music. With literature and words, we communicate with one another. It ends up person to person, knowing somebody and being able to talk to them.”

Flossie began showing her paintings around California, in gallery and museum exhibits, and even had a series of art shows in Italy.

With her newfound passion for art, Flossie began a mission to bring arts and culture to north Orange County, a culturally desolate place at that time. She describes organizing the Orange County Art Association in the early 1950s: “We didn’t have any art in this end of the county. Laguna always had some art going on at their museum, but the northern part of Orange County really had no viable outlet for artists.”

Then, as now, it was a challenge to convince the more conservative people of north Orange County to accept contemporary art. Flossie recalls: “That was when there was the transition of people thinking about contemporary things. Orange County was very traditional and very conservative, especially in north Orange County...People were doing red barns or those green trees; you better believe they were hard customers to convince because they were not going to relinquish their ideas and their ideals and the way a painting should look...There was a battle royale over that.”

Eventually, through persistence and strength of personality, Flossie succeeded in starting the Orange County Art Association. She also helped to found the “Night in Fullerton” event in 1966, to help promote and showcase local art and culture. She recalls: “We had to think of all the disciplines: music, dance, and theater. So we went to the schools to see what they had. Of course, we had a university. They had an art department and a drama department, and the Fullerton College certainly had all those things. Then there was the Muckenthaler which had just been presented to the city...what should we do about it? We thought that when we opened the Muckenthaler, it would be nice to have a cultural event. We organized all the various places and had them put their best foot forward, calling it ‘A Night in Fullerton.’”

Flossie created a committee to organize and promote the event, and even went door to door to raise money for it. At first, according to Flossie, “the city didn’t pay for anything. This was a community project.” Eventually, the city got on board and helped with some of the costs. Flossie saw a need in her community and worked hard to fill it: “Why not be a cultural community if we can promote culture?” she recalled, “I’d like it, when people think of Fullerton, they could come here and find something good to look at, good music to hear, and a good dance to see and enjoy.”

For the rest of her life, Flossie worked hard to help build a real arts community in Fullerton, founding the CSUF Art Alliance, and showing her work at venues all over town, even well into her 80s. Because she was such a magnetic and well-loved figure, her birthdays were huge community events, with city officials and organizations getting involved. For her 85th birthday, the City of Fullerton presented her with the “Key to Our Hearts.”