In attempting to understand the early history of Orange County, I have begun reading the book Orange County Through Four Centuries by Leo J. Friis. Once you get past the overt racism, Friis' book turns out to be quite informative. Friis begins with a quote from Father Geronimo Boscana, one of the Spanish missionaries who accompanied the early conquistadors on their conquest of California:

“The Indians of California may be compared to a species of monkey for in naught do they express interest except in imitating the actions of others and particularly in copying the ways of the white men, but in doing so they are careful to select vice in preference to virtue.”

Friis’ account of the native population echoes the racism of the earliest missionaries and conquistadors: “Orange County’s first residents were Indians who dwelt without privacy in rude, brushwood shelters swarming with fleas and vermin.”

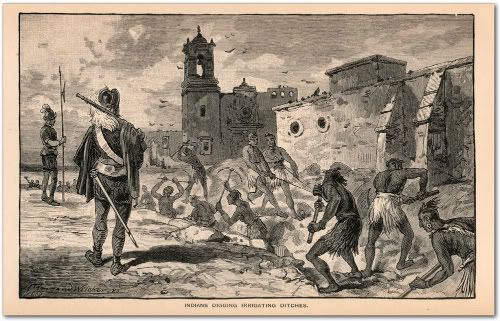

In his account of the establishment of the first missions and Spanish military outposts, Friis refers to the native inhabitants as “naked savages” and “the red man.” He again quotes Boscana to illustrate the way Europeans viewed the Shoshonean Indians, Orange County’s first inhabitants: “I consider these Indians in their endowments like the soul of an infant, which is merely a will accompanied with passions.” Guided by a feeling of cultural and racial superiority, the Spanish forced the Indians into missions in San Juan Capistrano, San Gabriel, and San Diego, where they tried to teach them the “superior” ways of agriculture, commerce, and Christianity.

The European enslavement of the Native Americans was not without resistance. Friis writes, “On the morning of November sixth [1775], distressing news arrived that San Diego Mission had been burned by the Indians and one of the padres slain. At San Juan Capistrano the Indians mysteriously vanished.” One wonders what was so “mysterious” about people not wanting to be subjugated.

Following this uprising, Governor Rivera ordered a “punitive expedition” against the Indians, which was fairly successful. On November 1, 1776, just four months after Washington, Jefferson and the “’founding fathers” of America were writing that “all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights…” the Spanish Californians succeeded in forcing hundreds of Indians back into Mission San Juan Capistrano, and putting them back to work.

What was life like for the Indians in the missions? Friis paints a rather disturbing picture: “When an Indian was baptized into the Christian faith he assumed the status of a neophyte. As such he was assured a definite supply of food, but in return he was expected to perform his share of the labor necessary to support the settlement. If he ran away to avoid his responsibilities he was pursued and brought back. If he committed a crime, he was punished by being placed in stocks or chained to a log or flogged.”

It is shocking how Friis sympathizes more with the Spanish oppressors than the oppressed Indians. “Through patience and kindness,” he writes, “they converted savages to a life disciplined to a reasonable amount of labor.”

There is an account of one Indian at San Juan Capistrano refusing his last rites from the priest. When asked why, he said, laying on his deathbed, “Because I do not want to; having lived deceived, I do not want to die deceived.”