Viewing Orange County land as a commodity to be exploited for profit, many of the early Orange County pioneers, and the companies they represented, did some pretty awful things to the land.

Under the “Drainage Act” of 1881, much of the Bolsa Chica wetlands were drained to make room for agriculture production and, later, oil. Many native animals and plants were, of course, killed.

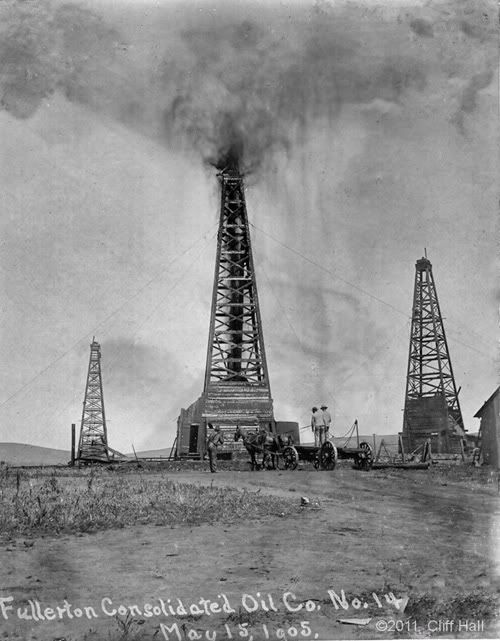

The Union Oil and Standard Oil companies delved greedily and deeply into the earth in cities like Brea, Huntington, and Fullerton, with little heed paid to the environmental consequences.

Charles C. Chapman, local orange grower and Fullerton’s first mayor, experimented with oil drilling. On March 11, 1919, he brought in a “gusher” on his property.

Hearing about this, the Standard Oil Company quickly leased land from Samuel Kraemer, literally across the road from Chapman’s property, and began drilling. Historian Leo J. Friis writes, “Three weeks later it spewed oil over twenty acres of Chapman’s choicest orange trees.”

This image of oil covering orange groves was a fitting prophecy, signaling the end of the era of the orange in Orange County, and the beginning of the era of oil. Charles Chapman’s son recalled: “For a number of years, we had noticed that along the highway the trees didn’t do well. We all thought it was dust or something like that. Then it began to be evident that it was the exhaust from the automobiles. As that increased, the damage increased.”

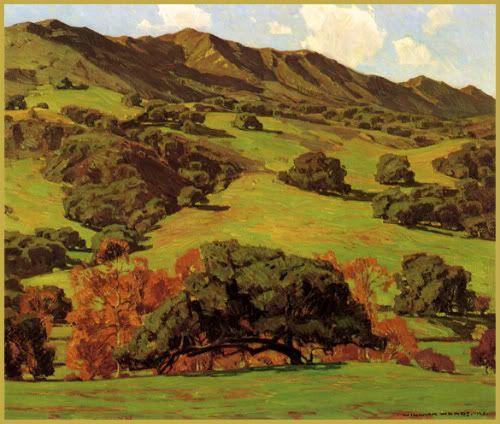

But not everyone saw the land as a commodity to be exploited. A pioneer who had a different view of the land was William Wendt, a landscape painter who came to Laguna in 1906 and painted many of the early, iconic images of the Southern California coast. He was described as “a deeply religious man, a quality of which was manifest in a reverent feeling toward nature and a kindly understanding of his fellow man.”

In my experience, artists are, by nature, poor business people, precisely because they care about nature and people. Despite this, Wendt was influential in establishing an artists’ colony in Laguna Beach, a colony whose legacy survives today.

Interestingly, The Great Depression in the United States was a great boon for the arts. It was a time unprecedented in American history. The government actually supported artists in a serious way, with the Works Progress Administration. Photographers like Dorothea Lange documented a side of America few had seen before: migrant workers and the poor.

Here in Fullerton, artist Charles Kassler was commissioned by the government to paint the beautiful fresco on the side of Plummer Auditorium “Pastoral California.”

The first “Festival of the Arts” in Laguna Beach happened in 1932, right in the middle of the Great Depression.

In 1930, Thomas E. Williams, a printmaking teacher at Santa Ana College, developed one of the first publishing groups in Orange County devoted to the arts. It was called, appropriately, Fine Arts Press. Historian Leo J. Friis writes, “He was a master craftsman and his work was an outstanding contribution to the typographical art and to book designing.”

As someone who is involved with the Downtown Fullerton Art Walk, co-owner of an art gallery and a fledgling printing press, I can’t help but see parallels between what happened during the Great Depression and what is happening today. When people don’t have a lot of wealth to distract themselves, they start to look carefully at the world. They start to see the world not as something to be exploited for maximum profit, but something to be appreciated, celebrated, and loved. At least that’s the way I see it.

Landscape by William Wendt