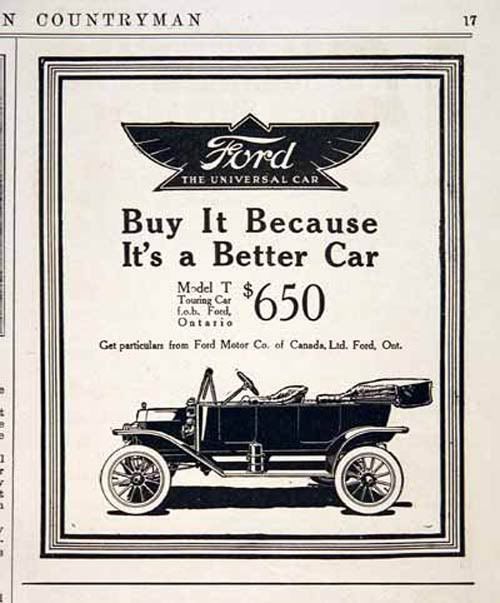

I always tell my students that, whenever they write something in an essay, they have to back it up with specific examples. So, I decided to do a bit of research on ads, to test Olin's hypothesis. I found one car ad from each decade, starting in 1914, and continuing to the present day. Let's take a look at them, and see if they are trying to sell something more than just a car:

Here's an ad for a Ford around 1914. In this ad, there is no real association between the car and something else. They just say, we make a good car. Buy it. No symbolic meanings there. So far, so good.

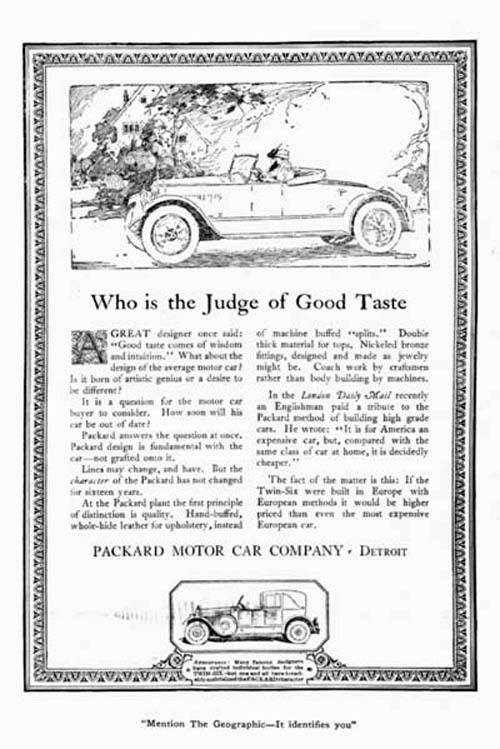

But here we have a car ad from the 1920s, and this ad does use irrational association. It suggests that, by buying this car, you are demonstrating your good taste.

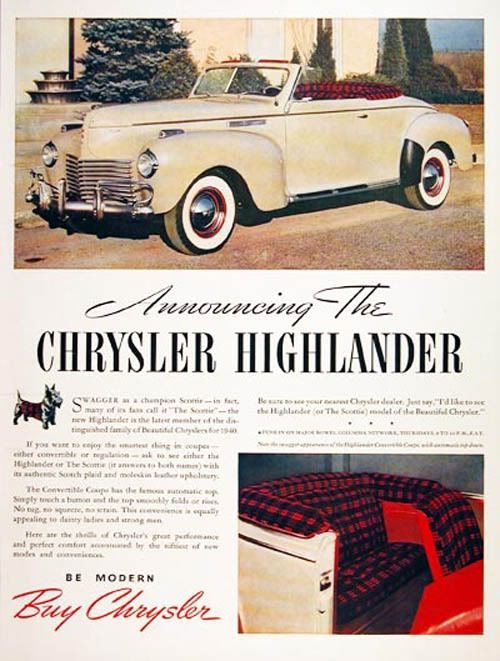

In this ad from the 1930s, the car is more overtly associated with some kind of upper-class, boating lifestyle.

This ad from the 1940s promises that, by buying this car, the consumer somehow becomes "More Modern."

In this ad from the 1950s, we begin to see the rise of that famous idea, "Sex sells."

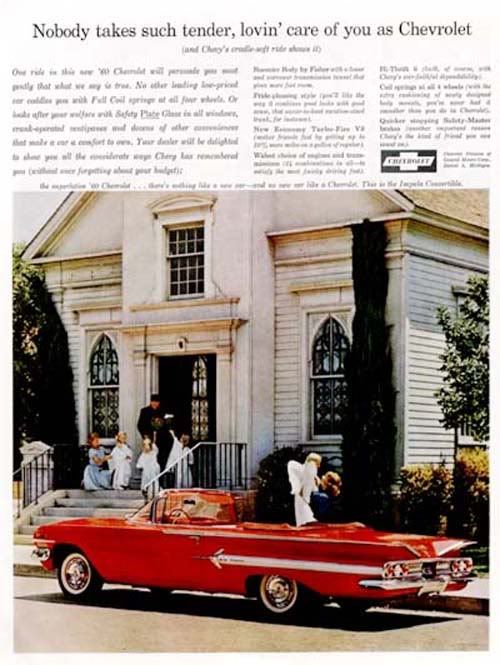

This ad from the 60s is interesting. it suggests that this car will make you more family-oriented and maybe religious.

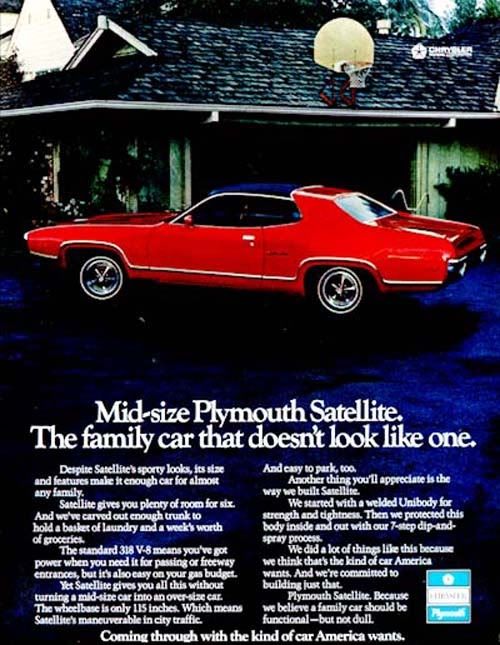

A couple things are being sold in this 1970s ad: family values and "sportiness."

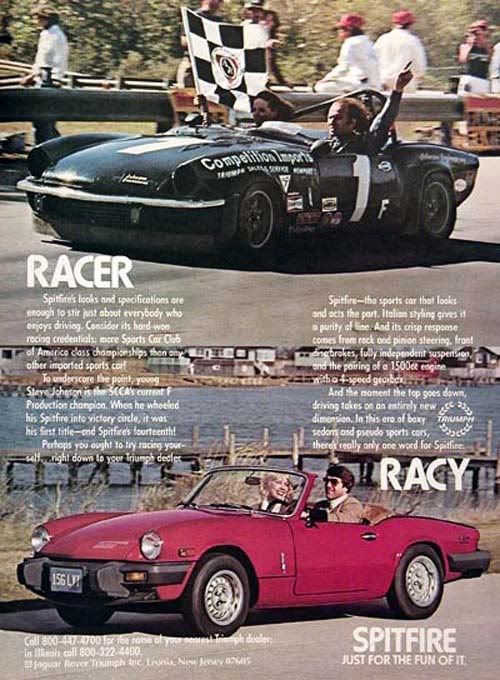

This ad from the early 80s is selling recklessness and sexual conquests.

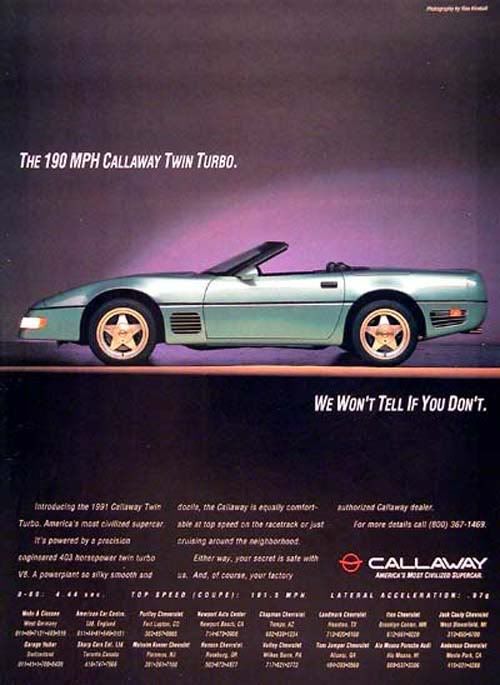

This ad from the early 90s suggests that it's okay to drive 190 miles per hour. They won't tell anyone.

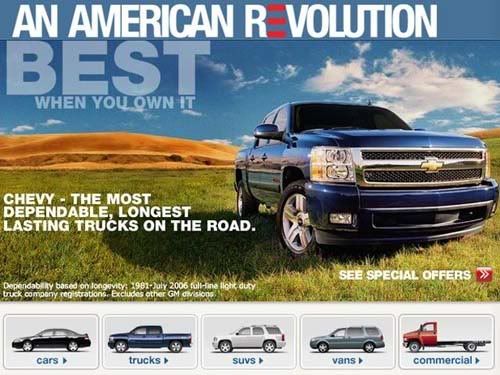

This Chevy ad is selling patriotism.

Thus, it turns out that Olin is pretty right on. Ads do not rely on clear and rational information. In a society as affluent as the United States, where wants outweigh needs, companies have learned to use nonrational emotional methods, whether they be a better lifestyle, sex, recklessness, or good ol' American values.