I used to work at Borders Books + Music in Brea. When I first started, the manager was a guy in his mid-30s who wore plaid shorts a lot and was very friendly. He was, for lack of a better word, “cool.” His laid-back attitude filtered down to the employees and made for a very interesting and pleasant work environment. I liked going to work there. I liked my co-workers and the customers and it was fun. I was encouraged to be myself, and I think that attitude made Borders a “cool” place to work.

But then that “cool” manager got transferred to another store and we got another manager who was definitely not “cool.” She came in with a laundry list of corporate-mandated things we had to do, like asking every single fucking customer if they wanted to join our e-mail list, and “upselling.” Upselling was a big deal for this manager. Whenever a customer asked for help finding a book or CD, we had to suggest that they buy something in addition to the thing they wanted. If, for example, someone wanted the new John Grisham novel, I might suggest that they also buy a book light, because that book was really going to keep them up at night, it was so thrilling.

I would joke with my fellow employees about trying to “upsell” customers things that were totally unrelated to the thing they wanted. If, for example, someone wanted How To Win Friends and Influence People, I might say, “If you like that, you might also like this book on self-mutilation.”

I never did this, however. The fact is, I could not bring myself to “upsell.” It felt sleazy and impersonal. I got written up like three times for refusing to upsell, which led to a series of conflicts with that manager that resulted in me quitting.

What made that job unbearable (for me) was the lack of freedom. I was not encouraged to innovate, to be myself. I was encouraged to fit a certain corporate-mandated mold, like a robot.

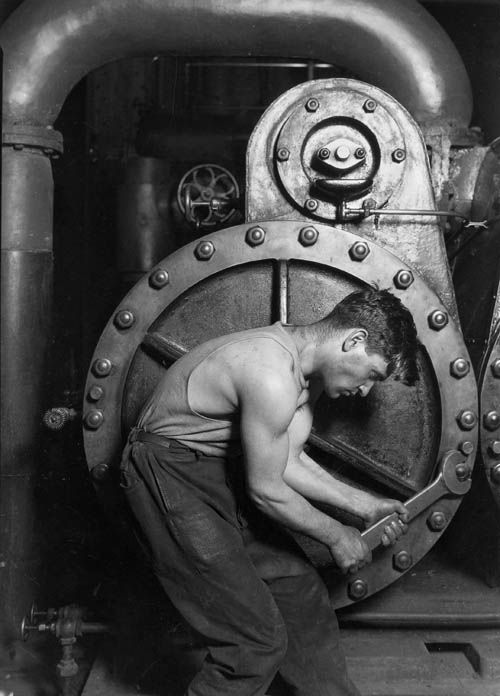

One summer, I had a job where I was actually asked to perform tasks very similar to those of a robot. I worked the graveyard shift for a company called First American Real Estate Solutions. I worked in a big black office building. My shift consisted of me sitting for eight hours in a cold room surrounded by big super-computers. I sat in front of a monitor, waiting for seven-digit numbers to pop up. When one such number popped up, I had to write it on a piece of paper and then go into this huge warehouse containing millions of numbered cartridges. I had to find the cartridge with the corresponding number and place it in one of seven “drives.”

I know it sounds like I am making this up, like it’s something out of Brave New World, but I swear I’m not. I remember sitting in front of that monitor in my hooded sweatshirt, coughing from a chronic cold, and reading Crime and Punishment. It was a pretty depressing time in my life, actually.

So, what is my point? I suppose what I’m saying is that, at least for me, work must have meaning. I stayed in school way longer than most of my friends because, after having worked for corporations, I could not bear the idea of working a corporate job. The thought was painful. So, after college, I endured three more years of poverty, while earning my Master’s degree, so I could get a job teaching at a community college, which seemed like the thing I would most like to do, aside from being a famous writer. I love being a teacher.

We give so much of our lives to our jobs. I had a teacher in college once describe this transaction as “time” for “money.” But, given the fact that our lives are so short, why settle for a job that doesn’t allow us to use our full potential as human beings? Albert Schweitzer, Nobel Peace Prize winner, said, “Search and see if there is not some place where you may invest your humanity.”

I understand that people need money to survive and provide for themselves and their families. But I don’t think that is an excuse to settle for a boring, mind-numbing job. At the community college, I have taught single mothers on welfare, who were going to school because they didn’t want to work in a factory or retail. They wanted to follow their dreams, even though it meant being kind of poor, at least for a while. In my experience, being poor is not nearly so bad as being unhappy.