“Why settle for some know-it-alls

despair when the dead

may dance to the fiddle

hereafter, for all anybody knows?”

--Wendell Berry, “Testament”

Dear Beatrice,

I have a tattoo of Dostoyevsky on my left arm. When I show people, they sometimes ask, “Why?” I tell them, “Because he is my favorite writer.”

If they ask me, “Why is he your favorite writer?” I tell them, “Because he understood that beauty is not possible without pain. Because I read The Brothers Karamazov when I was at the lowest point in my life and it taught me that suffering can have meaning, that suffering need not be the end, that it can also be the beginning of something astonishing.”

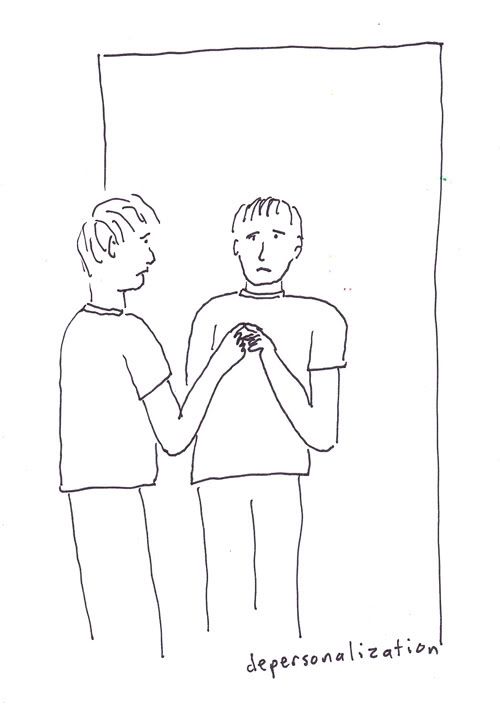

Last night Landon asked me to describe what depersonalization feels like. And still, after all these years, I could not describe it. Strange. This is the wound I still carry, and may carry for the rest of my life. This is the wound that has driven me to become what I am—for better and for worse.

Sincerely,

Jesse

It’s easy to confuse depression and fatigue. Tonight I was laying on my couch, after watching a mediocre legal thriller on Netflix, and I wanted to do nothing, and that made me kind of depressed.

So I made myself get up and walk to Ralphs and buy groceries to make dinner. As I’m walking, I listen to Daniel Johnston on my ipod, and it’s inspiring. When I get home, I feel compelled to write. Sometimes all it takes is a walk and some good music to get me out of a funk.

I am tired. Do most people think about these things? I sometimes wonder how my day-to-day suffering compares to the average person. I heard today that one in six people has some kind of mental illness.

I suppose that’s another thing I want this book to accomplish—to help erase the stigma, the fear of mental illness. To bring my experience to light with the hope that it might help people talk about the pain they hide. To bring it into the light, and have a conversation about it. I think that might make people less lonely.

...

Depersonalization. Walking along Harbor Blvd, I look at my reflection in passing building windows.

Depersonalization. Standing in my doorway, looking out at overcast, rainy skies. A lone seagull beats against the falling rain.

Depersonalization. I take these medications, I go to therapy just to be functional. I have passions and I follow them, but sometimes it is like a striving in the dark, like a fight to be here fully. But I don’t need to be happy all the time. I just need to mean something.

Depersonalization. I tell myself that I want to feel these things, but some of them are so potentially painful that I don’t know if I can bear them. If I felt the full weight of unbelief, of loneliness, of fear, of general bewilderment at life. What is hard is surrendering control, letting the feelings pass over and through me like waves, knowing I will survive.

Depersonalization. Two years ago, age 29, when it was so bad I wanted to die, and I broke down and sobbed and wailed like a baby in my parents’ arms.

Depersonalziation. We think that, as adults, we are so composed, so mature. However, beneath the surface, there are all these leftover childhood fears, insecurities, selfishness, anger, loneliness. It gets buried, but comes out in our dreams, our actions, our relationships, our mistakes.

Depersonalization. I feel a compulsion to write. I feel writing will help alleviate my suffering. I understand something about myself—writing is my bridge to reality. Sometimes when I write something, I feel a compulsion to read it over and over again, as if to prove to myself that I am here, that I exist.

...

“Lisa, am I incapable of feeling?”

“What do you think?”

“I mean, I feel things. I feel frustation, loneliness, joy sometimes. But I guess my question is this—if all this pain and detachment and anxiety and depression is a defense mechanism against really feeling, how will I ever really feel?”

“You will feel how you will feel. There are no templates. There’s no right way to feel. You will feel as you learn to feel. I think you learned to hold things inside for so long that feeling is scary for you.”

“Growing up, I did not know how to feel, or to let it out.”

“Let me give you a scene. You are at church.”

“I don’t like church.”

“But this is different. This is not a big mega-church. This is a little catholic church in Mexico.”

“Why Mexico?”

“Just go with it.”

“There is a little old lady in the church and she is praying for you.”

“I hate it when people pray for me.”

“But this is different.”

“She is not praying that you will feel better. She is just praying that you will feel. She is there with you, holding your head. Her prayer is very short. You don’t even understand the words. The real prayer is her presence. She is there with you, in your feelings. And then they come.”

“I don’t want them to come. I am afraid. I am afraid I will lose control. I am afraid I will go crazy or die.”

“But this old woman stays with you. She gives you permission to feel and she gives you a promise—you will not die. You begin to feel.”

In Lisa’s office, I begin to cry.

“No. No. I don’t want this.”

“It’s okay. I am here.”

“Oh Jesus. Oh God.”

And then I really come apart, wailing, weeping.

“Oh Jesus. Oh fuck. This fucking hurts.”

Lisa puts her hand on my shoulder.

“I am here. I am here.”

...

When we first meet, it will be wonderful. We will have so much to talk about, like ideas for special dates we can go on and it will be fun.

The first time we attempt sex, I will have erectile dysfunction and I will blame it on the alcohol and the Paxil.

But the second time it will be great.

We will hang out all the time and be a real couple and we won’t feel lonely.

But then you will get a little “clingy” and, being an essentially introverted person, I will feel uncomfortable. When you grab my arm in public all the time, I will secretly think, “I don’t want to be your crutch.”

And after a while, our phone conversations will be replaced by texts, and you will text me way more than I will text you, and you will want to hang out every day, and I will actually start to kind of resent you, and I will feel guilty about this.

I will send texts to other girls sometimes.

I will tell you I need space.

It will take me a while to work up the nerve to actually break up with you, and I will get anxiety and stomach pains and I will be afraid you will try to kill yourself or something.

And after we break up, I will go on a two-week bender and get drunk and chain smoke and have sex with two other women who I’m not really even interested in and I will feel guilty about this too.

One night I will see you at a bar and get drunk and end up having sex with you on my couch and I will feel like a piece of shit in the morning. And we won’t talk for a while and my bender will continue until I think I have an ulcer that will turn out not to be an ulcer.

And every night, I will send increasingly desperate drunk texts to every girl I’ve ever liked, and some I didn’t, whose number I still haven’t deleted. I will text lines of sad poetry, and sometimes they will respond in the morning with responses like “What the hell?” or, more commonly, “WTF?”

I will not cut my hair or beard for a long time.

I will consider visiting a girl in Arizona, but I will not.

And eventually my life will settle back into it’s normal routine of writing and teaching and loneliness and an ever-deepening cynicism about love.

...

In a dream, I had a wrestling match with my id.

This guy walked in my room, kicked in my mirror, and started wrestling me. I was trying to explain to him about how, in society, people agree to follow certain social contracts, where they don’t do things, like kick in peoples’ mirrors.

I tried to reason with my id, but I got the clear impression that he didn’t give two shits about reason or social contracts. He wanted to do what he wanted to do. That was all.

I grabbed his pinky and began to bend it back, like I was gonna break it. But then I stopped, and tried to explain how, by not breaking his finger, I was following a social contract, to not randomly hurt people. He seemed disinterested.

It was really frightening to meet someone who has zero sense of morality. But, according to Freud, that person lives inside us all.

...

“When you look at the sky, what do you see?”

“Blue. Clouds.”

“I see blue, but I see it as millions, billions of tiny points of light. If I look at anything in a sort of unfocused way, that’s what I see. Even the night sky.”

“That’s kind of weird.”

“It’s called photosensitivity. For some reason, I can’t stand fluorescent lights. They give me anxiety.”

“Hmmm.”

“So like when I look at things and see these tiny points of light, I’m consciously aware that what I’m ‘seeing’ is really just my brain’s interpretation of things. Cones and rods and shit.”

“Are you sure you’re okay?”

...

Tonight I sat alone on my rooftop and cried to myself and said aloud:

“I want to feel normal. I want to stop hurting.”

...

I’m sitting at Maclain’s next to a group of five men and one woman who seem to be friends from either AA or NA or both. That’s what I gather from bits of their conversation.

This guy with a shaved head and goatee tells a story about “The best seven days of his life,” which he spent on a beach in Costa Rica with these women whose sole function seemed to be to bring him beer, carry his surfboard, and have sex with him.

“Girls were like that in ‘Nam,” another guy adds, “Submissive.”

The first guy tells a story about how he saw and took a picture of a demon in the jungles of Panama.

“You wanna see a picture of a demon?” he says.

A bit later, I overhear the woman say, “So that’s when I found out I was pregnant. I was drinking tequila at the bar and kept throwing up and didn’t know why. Turned out I was pregnant.”

...

When I come to class, I am tired and my voice is scratchy. I think of cancelling class, but I stick with it. I start teaching and, as the class goes on, I feel my energy increasing and my voice getting clearer. Sometimes you have to just do something even if you feel powerless to try. The strength comes in the doing.

...

Dear Astrazeneca,

I take your medicine Seroquel so that I won't slip into suicidal depression. I was wondering why it costs me $280 every month. Because I have pre-existing conditions, I am unable to get health insurance, and so I must pay this exorbitant price every month out of my own small paycheck. I just feel like I'm getting ripped off. $280 for 30 pills seems a bit steep. I am aware of your "research and development" costs, but still. Come on, guys.

Sincerely,

Jesse La Tour

English Instructor

Fullerton College

...

My car is a mess of papers, water bottles, fast food wrappers, books. My room is strewn with ungraded papers. My kitchen is full of dirty dishes. My storage room is a mess of photographs, canvases, paints, and artworks in progress. Weary yet inspired, I move forward.

...

I’ve just finished showing my English 101 class the film “Dancer in the Dark” and we get talking about tragedy and I say,

“Yes, it’s tragic. But the Greeks had this idea called a catharsis, which suggests that a watching a tragedy can cause you to reflect on your own life, on your relationships, and release the negative emotions you feel, and so a tragedy can actually be good for you.”

I look out on a sea of blankish stares.

“That’s what the Greeks thought, anyway.”

...

At the Continental tonight, I feel out of place. Don’t feel like drinking, smoking or meeting girls.

Instead, standing alone outside, I meet a young man in the Army, about to be deployed to Afghanistan. I can see the fear and bewilderment in his eyes. He says joining the army was the worst decision he ever made. He says he joined because he had a drug problem and wanted to do something productive. But what he has seen and what he has done makes him want to do more drugs. I think of my cousin Steve, who came home from the Gulf War and got addicted to meth and now lives with his grandmother.

I feel like crying.

I put my hand on the young man’s arm. I want to pray for him, but I don’t know if he believes in God, so instead I say, “I’m sorry. I feel for you, man. It’s gonna be alright.”

If I wasn’t so damned depressed, I would stay and drink with the guy, just so he’d feel better, less alone, more normal. But I have to get out of this place.

On my way out, I pass Lana dancing with some weird dude who looks like he’s in Marilyn Manson—the same guy I once saw her kissing, the first night she invited me to hang out and she got drunk and made out with this same dude and I told myself,

“This girl is not for me.”

...

An evening alone. English 100 essays, facebook, Stouffers lasagna, cigarettes, porn, George W. Bush’s facebook page, e-mail, old Nintendo games, loneliness, ignored texts. Tomorrow will be better.

...

I am riding in the back seat of my grandpa’s old Buick, sitting next to my grandma Sally. My brother sits in the front seat, filming my grandpa as he talks about this place. Reedsburg, Wisconsin. The place he grew up. The place he will be buried. My grandpa has acute leukemia and has less than a year to live.

He is leading a caravan of cars through this green, hilly countryside. It’s a little pilgrimage he leads once a year. Much of the Midwest is flat farmland, but this land rolls on for miles, hills and valleys and streams, little farmhouses dotting the landscape. It reminds me of Ireland.

We stop on a little dirt road and get out. Down a winding gravel driveway sits an old wooden house. This is where he lived. Down the road a bit, a man is driving a tractor. He pulls up to the house and grandpa greets him warmly. It is his nephew.

We take pictures outside the little house and grandpa tells stories about how, during the Depression, his mom and dad used to make moonshine and sell it at local dances. He talks about walking miles to get milk from a local farmer. There is a solemnity and a nostalgia to his words, as if he is looking into the past, to a time before agro-business and development pushed the small farmers off the land.

We continue to another little wooden building that looks abandoned. The wood is rotting and the paint is peeling, but it still stands.

“That was my school,” grandpa says, “I used to walk two miles every day, except in the winter, when I had to take care of my brother and sister.”

At age 9, grandpa had the responsibility of keeping his house warm and his brother and sister fed and clothed. His step-dad worked in a factory. His mom was grieving the death of her father and husband in an auto accident.

The last stop is Big Creek Cemetery. There are grave stones bearing the names of my ancestors, dating back to the 1800s. Steffen. Poff. Miller. Atop a big rock is a metal placard with the names of my grandparents, aunts and uncles. This is where grandpa Glenn will be buried in less than a year. This is where I, too, may be buried.

We take pictures together. The little kids run around looking at gravestones. I am taking photos of my grandpa. I try to name what I am feeling. It’s not sadness exactly. In little towns like this, cemeteries are a part of the landscape. Death is a part of life. These stone monuments remind us of who we are and where we came from. I feel the weight of the past, present, and future. I feel my mortality. I don’t want my grandpa to die, but he will die. We all will. And yet, there is a certain solemn comfort in knowing that this place exists. Even grandpa does not look sad. He carries his usual husky swagger, a softness in his eyes, and a pride in his homeland. This is where we all come from, and it is beautiful.

...

My father does not have a middle name, so I don't have one either. Sometimes I wonder if that is why we are so restless. We are searching for our names, as if to say to our fathers, "Why did you leave me this emptiness?" And I imagine saying to my future middle name-less son, "So you would learn to fill it. Go, my son, and find a name for yourself because no one, not even your father, can tell you who you are."