I am proud to be part of an emerging arts scene in Fullerton, a city not historically known as a center of progressive cultural activity. Things are changing. The city is becoming more diverse--culturally, artistically, and politically. My friend Stephan "Bax" Baxter has become one of the most proactive and interesting proponents of the arts in Fullerton. At his smallish gallery in The Magoski Arts Colony, The Egan, Baxter continues to show fantastic emerging art, and he is a tireless champion of culture in this historically conservative city.

The next show at The Egan is perhaps his most ambitious and exciting yet. It's a massive collection of Chicano, folk and other outsider art, ceramic sculpture, assemblage, paintings and rare oddities, which have been acquired by premiere local collector Enrique Serrato over the last 50 years. Enrique’s collection, (over 6,000 original artworks) is one of the largest private collections of Chicano and outsider art in California. It all began with a single small bowl by an El Sereno potter which he purchased in 1962 and his passion for art and collecting continues to this day.

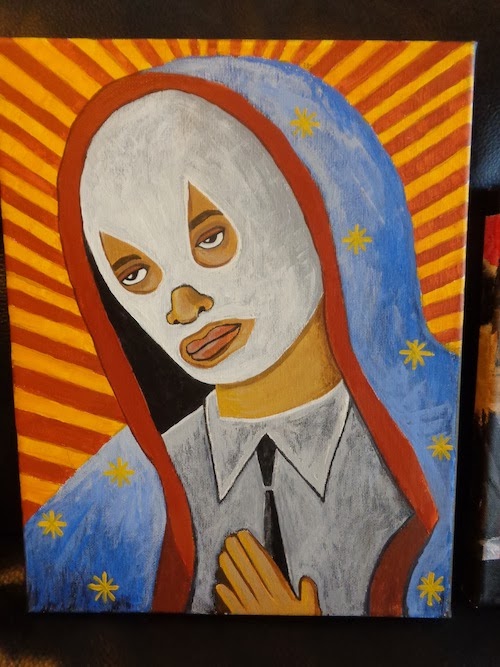

Here are some of the world-class artists from Enrique's collection which will be on display at The Egan this Friday, January 3 from 6-10pm during the Downtown Fullerton Art Walk...

Alcaraz is the creator of the first nationally-syndicated, politically-themed Latino daily comic strip, “La Cucaracha." His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Village Voice, the L.A. Times, Variety, and many other publications. Alcaraz and his work have been featured on CNN, PBS, NPR, and lots of other places. Lalo’s books include “Migra Mouse: Political Cartoons On Immigration, (2004). He is is the co-host of KPFK Radio’s wildly popular satirical talk show, “The Pocho Hour of Power,” heard Fridays at 4 p.m. in L.A. on 90.7 FM, and co-founded the seminal Chicano humor ‘zine, POCHO Magazine. Alcaraz also co-founded the political satire comedy group Chicano Secret Service.

Born in Tepic Nayarit, Mexico, Esau Andrade comes from a family of folk artists which includes his mother and his brother, Raymundo. Although largely self-taught, he attended La Escuela de Artes Plasticas de the Universidad de Guadalajara. Esau's paintings are included in the collection of The Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, CA as well as in the Downey Museum of Art in Downey, CA. He has had exhibitions at Galeria Uno (Puerto Vallarta), the Chac Mool Gallery (Los Angeles), Louis Stern Gallery (Los Angeles), Alene Lapides Gallery (Santa Fe, New Mexico) and Euroamerican Gallery, New York, among many others.

In the early ‘80s, Gamboa photographically documented the East Los Angeles punk rock scene. She was associated with ASCO. Gamboa organized numerous site-specific "Hit and Run" paper fashion shows — created as easily disposable street wear. During the ‘90s, she found herself using the tension and stress involved in the urban environment to create new works, leading her to develop a Pin Up series of 366 ink drawings on vellum as an in-depth study of male-female relationships. These works led to her “Endangered Species” series, which recreates some of the Pin Up drawings in a three-dimensional form. Many of the figures in the Pin Up drawings are covered in tattoos, which is an ongoing fascination for Gamboa.

Gilbert "Magu" Lujan co-founded the famous Chicano collective Los Four, along with Carlos Almaraz, Beto de La Rocha (Father of former Rage Against the Machine frontman Zack de la Rocha), and Frank Romero. In 1974, Los Four exhibited LACMA's first-ever Chicano Art show, appropriately called "Los Four." This was quickly followed by several other exhibitions on the west coast. Los Four did for Chicano visual art what ASCO had done for Chicano performance art; that is, it helped establish the themes, esthetic and vocabulary of the nascent movement. In 1990 Magú was commissioned as a design principal for the Hollywood & Vine station on the Metro Rail Red Line in Los Angeles. His work uses colorful imagery, anthropomorphic animals, depictions of outrageously proportioned lowrider cars, festooned with indigenous/urban motifs juxtaposed, graffiti, Dia de los Muertos installation altars and all sorts of borrowings from pop culture.

Ever since bursting onto the scene in the late 1980s, Yolanda Gonzalez has had a tremendous impact on Chicano art, producing work at a whirlwind pace. In less than ten years, Gonzalez has evolved from a talented hairdresser, taking part-time art classes, into one of the most prolific artists in Southern California, currently running the MA Gallery artspace in East Los Angeles. Her rapid ascent makes it hard to remember that she is really still one of the "new" faces. Gonzalez, a California native, studied at Self Help Graphics in the mid-1980s and was formally introduced to the public at the First Annual Nuevo Chicano Los Angeles Art Exhibition at Plaza de la Raza in 1988. Since then she has traveled to Japan, Russia , Spain, and Scotland creating a number of commissions, notably a huge 15 foot retablo on canvas of the Virgen de Guadalupe for Floricanto USA. In addition to her career as an artist, Gonzalez also teaches art at Inner City Arts, an organization for underserved youths.

Alfredo de Batuc grew up in Mexico and his work shows the rigorous training in drawing of Mexican art schools. His work can be found in private and public collections including but not limited to: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, California State Supreme Court Building (San Francisco), Museo Estudio Diego Rivera (Mexico City), Laguna Art Museum, Latino Museum (Los Angeles), and UCLA's Fowler Museum of Cultural History (Los Angeles).

Tony de Carlo is a native of Los Angeles. A self-taught artist, he has been creating art on a daily basis since his childhood. His work is exhibited regularly in museums and galleries throughout the United States, and his paintings are in collections around the world. The paintings of Tony de Carlo have been exhibited at: Santa Monica Museum of Art, The Carnegie Art Museum, Riverside Art Museum Art, Laguna Art Museum, SPARC and UCLA Caesar Chavez Center, and his work was featured in the 2002 season of "Pageant of the Masters" in Laguna, California.

Garcia's work has been exhibited in group shows throughout Southern California as well as in Texas and Mexico. García teaches and lectures extensively on art in different cultures. She has said that her work "provides a look at my community through the presence of the individual." Although she does not consider her portraits overtly political or even socially conscious, in time she has come to realize that their very specificity belies the stereotypes given to any one culture by the media.

José Lozano was born in 1959 in Los Angeles. In 1960, he moved with

his mother to her birthplace of Juárez, México. There, he found many of the

cultural touchstones that continue to influence his work today-bad Mexican

cinema, fotonovelas, ghost stories, comic books, and musical genres such

as bolero and ranchera. He returned to Southern California in

1967 where he attended Belvedere Elementary School in East Los Angeles at which

his teachers encouraged him to draw and paint. He began creating revealing, yet

not always flattering, works about his neighborhood and its residents--demonstration

parties, quinceañeras, weddings, and baby showers. Later, he received

his Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts degrees from California State

University at Fullerton. Lozano prefers to work in a series and focuses on

particular themes and topics, such as Mexican wrestlers, paper dolls, Mexican

movie imagery, clowns, lotería, and figures in midair. Most of his work

is referred to as "morose," a trait of many artists that he

prefers.

These are just a handful of the many artists who will be featured in this exhibit. Here are some more images of artwork from the show:

Ricardo Gonsalves, another integral part of Fullerton's emerging art scene, and a complete intellectual badass, is co-curating the exhibit. Other notable local art patrons like Alfredo Gutierrez and Michelle Buck & Jeff Middlemiss have been invaluable in narrowing the collection down to 100 of the best pieces. It’s a momentous task and an essential show.

Baxter said, "We have decided to curate the exhibit to give guests a hint of the feeling we first got when we walked into Enrique’s home. Upon our first glimpse of Enrique’s living room we were thrilled and overwhelmed, as I imagine everyone who has an appreciation of art would be. There was so much art in a small space. It was art, upon art, upon art, and everything I saw was exceptional. In order to reproduce this feeling we plan to stack sculpture and paintings from floor to ceiling. We will go so far as to enlist the aid of cabinets and shelving similar, to what one might find at Enrique’s house. It will be unlike anything ever exhibited at the Fullerton Art Walk and a rare opportunity for art walkers to benefit from Enrique’s critical eye and to do so at prices which reflect a collector who is motivated to share his art."

The opening reception for "The Enrique Serrato Collection" at The Egan Gallery is Friday, January 3, 2014 from 6-10pm during the Downtown Fullerton Art Walk. The Egan Gallery is located inside The Magoski Arts Colony at 223 W. Santa Fe. Ave in Fullerton, California.

|

| Enrique Serrato in his living room. |

The opening reception for "The Enrique Serrato Collection" at The Egan Gallery is Friday, January 3, 2014 from 6-10pm during the Downtown Fullerton Art Walk. The Egan Gallery is located inside The Magoski Arts Colony at 223 W. Santa Fe. Ave in Fullerton, California.

Don't miss this amazing show!