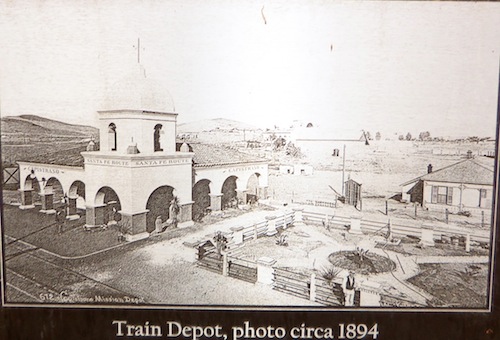

The historic San Juan Capistrano train depot, built in 1894, is now a restaurant called Sarducci's.

I spent some time wandering the Los Rios Historic District, which is a very popular place for people to take wedding pictures. I was more interested in the plaques and landmarks that told the story of this place. I couldn't help but feel the strange irony of people taking wedding photographs on the site of something as dubious as a Spanish mission. I wonder how many of the people taking pictures are even aware of the ugly realities of Mission life, especially for the Acjachemen Native Americans, who were forced to live here.

Here's the Rios residence, the oldest in the area...

Built in 1794 for Feliciano Rios, a soldier attached to Mission San Juan Capistrano who came to Alta California with Father Serra in 1776, the Rios Adobe is the oldest continually occupied residence in California and is currently home to the 10th generation of the Rios family.

Great, great grandson of Feliciano Rios, Damian Rios was a renowned horse trainer sought out by clients around the world for polo ponies. His wife Gertrude opened a restaurant in their home, the Rios Adobe, in 1927 and expanded it by building the cookhouse that still stands in front of the adobe.

Polonia Montaez was one of the village midwives, and was responsible for the religious education of village children when there was no priest at the Mission. Regarded as a spiritual healer and knowledgable about medicinal plants and herbs, Polonia was acknowledged as the village healer.

There is an interesting wall of plaques telling the story of the Los Rios District. The first plaque reads: "Like much of San Juan Capistrano, the Los Rios Street Historic District and surrounding area was home to Native Americans of the Acjachemen Nation before Mission San Juan Capistrano was established in 1776. The first adobe homes for Mission neophytes (that's what the Spanish called Native Americans) and soldiers were built here in 1794, some of which remain to this day, including the Rios Adobe, Montanez Adobe and Silvas Adobe. Wood-framed structures began to be built in the late 1880s and into the early 1900s. The Los Rios Street Historic District is the oldest continually occupied residential street in California. Many historic families of San Juan were and are connected to the Los Rios area, including the Rios, Lobo, Ramos, Yorba, Labat, Olivares and other families. The Los Rios Street Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. The area's rich history is depicted by the photographic plaques placed along this Historic Depiction Program wall in 2009." Not many people there seemed interested in the plaques, unfortunately.

The plaques tell interesting stories of people who lived here, like Modesta Avila...

In 1889, Modesta Avila objected to the Santa Fe railroad running through her mother's land and hung a line of laundry across the tracks. Although she removed it before the train arrived, she was later charged and convicted of a felony, sentenced to three years in San Quentin, and died there at age 22 after serving two years of her sentence.

Clarence Lobo lived on Los Rios Street for much of his life, and was elected chief of the Juaneno Band of Mission Indians, Acjachmen Nation, in 1946. He represented his nation for 39 years seeking to obtain federal recognition for the Juanenos and championing the plight of Native Americans.

Native American scholar Edward D. Castillo writes, “Despite romantic portraits of California missions they were essentially coersive labor camps organized primarily to benefit the colonizers.” Because of diseases and conflict with the Spanish colonizers, about 100,000 or nearly a third of the total Native American population of California died as a direct result of the California missions.

Maybe one of reasons why the real history of the California Missions is not widely known and talked about is because it's SUPER depressing, and bad for tourism and business.