Last week, I discovered that the Fullerton Museum Center’s next exhibit is all about the orange groves of Orange County. It’s called “Citrus: California’s Golden Dream.”

Upon learning this, I was struck with a sense of purpose. I thought…I can possibly contribute something meaningful to this exhibit, based on all the research I’ve been doing. So I compiled some of my recent research and writings into a paper entitled “The Orange County Citrus Industry from the Perspective of the Workers.” I described the conditions of the Chinese, Japanese, and Mexican orange pickers throughout Orange County history. These workers faced exclusion, segregation, housing discrimination, and overt racism. I think it’s important for the Museum’s exhibit to tell this side of the story, so it does not become a dishonest “puff piece.”

Three days ago, I e-mailed my paper to the Fullerton Museum Center curator. I have not yet received a response. Since then, I found another excellent paper in the local history room entitled “Citrus Culture: The Mentality of the Orange Rancher in Progressive Era North Orange County.” It was a Master’s thesis written by Laura Gray Turner. A chapter entitled “Laborers in the Groves” sheds further light on the conditions of the workers. Here’s what I discovered.

Some of the first orange laborers in Orange County were “native sons of now divested old ranchero families.” Before the United States conquered California and took it from Mexico by force in the Mexican-American War, much of the land was subdivided into large ranches, owned by Mexican families. When the U.S. took over, many of these ranchers lost their lands. Their children, stripped of property, wealth, and land, ended up becoming laborers in the groves of a new wealthy, white American elite, like Fullerton’s own Charles C. Chapman.

In the late 19th century, with the construction of the trans-continental railroad, a new minority labor force entered California..the Chinese.

Conditions for the Chinese laborers in the orange groves were not ideal. Turner writes, “Six days a week they labored, often sleeping under the trees in the groves…in crude bunkhouses or small shanties…wages were probably about a dollar per day.” Chinese, like other minority groups, were forced to live apart from the dominant/white community. According to Turner, newspaper accounts of the Chinese presence in Orange County “reveal a certain ‘we-they’ mentality and a sense of social superiority exhibited by the white grower elite.”

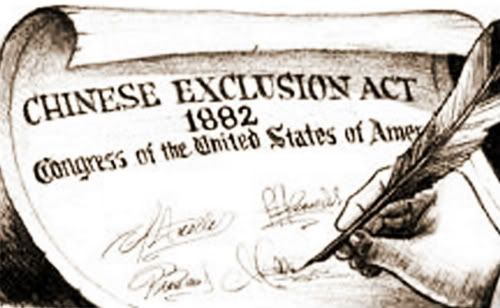

In 1882, the U.S. government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which made official what was already widely practiced. Chinese were forbidden from becoming U.S. citizens.

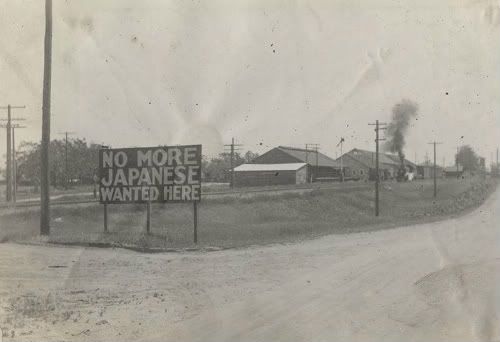

With increasing anti-Chinese sentiment, a new group entered the citrus labor force…the Japanese. Turner writes, “Anticipating the eventual drift of the hate campaign of the northern California urban press and labor unions to turn on them, Japanese moved into the more receptive environment of southern California agriculture.”

Conditions for the Japanese laborers were, however, not ideal. One orange grower, George Key, recalls: “There were about twenty men living in a one room building made of rough 1” x 12” boards, no flooring, no windows, and one door. Smoke from the open fire had to find its way out the door or through the cracks. An open hole in the ground a little ways from the door received all refuse.” This type of housing reminds me of the housing I observed when I visited the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland.

When the Japanese laborers began to organize to assert their human rights, “Orange County growers joined the chorus of opposition to ‘Japanese immigration, ownership, or even leasing’ of land.” This sentiment ultimately let to the Alien Land Laws of 1913 and 1920, which forbade Japanese people from owning property.

The increasing anti-Japanese sentiment let to a need for a new/cheap labor force, and growers looked to Mexico, the labor pool that would dominate the industry for the remainder of the 20th century. Who were these Mexican laborers and what was life like for them in Orange County? George Key recalls: “The first of the Mexican laborers coming from Mexico were very poor and uneducated. Most communities had ‘Mexican settlements.’ Because these people were poor and knew nothing but poverty, they worked for small wages. Living conditions were deplorable with makeshift shacks and outdoor toilets.”

Like the Chinese and Japanese laborers before them, Mexican laborers faced exclusion, housing discrimination, racism, and occasional forced deportations, like during the Great Depression, when white people needed jobs.

The Orange County citrus industry was characterized by the very darkest manifestation of American capitalism: a wealthy elite, with the help of government, making enormous profits on the backs of an exploited, second-class labor force.

I hope the Fullerton Museum Center curator has the integrity to represent this tragic reality in the “Citrus: California’s Golden Dream” exhibit.